*Dramatic Voice* Previously, on Blue Cereal Education…

*Dramatic Voice* Previously, on Blue Cereal Education…

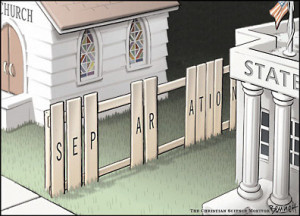

I recently proffered a brief overview of the whole ‘Wall of Separation’ idea in American jurisprudence, then dove into a few early Supreme Court Cases involving religion and public schools.

We looked at Everson v. Board of Education (1947) in which the Court determined it was perfectly acceptable for the state to reimburse parents for transportation costs of getting their children to school, whether public or private, sectarian or secular.

Then came Engel v. Vitale (1962), in which the Court made clear that the state could NOT require – or even promote – prayer in public schools as part of the school day. It was followed closely by Abington v. Schempp (1963) in which the same decision applied to the reading of Bible verses or the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer.

In neither case was the goal to drive faith out of public education. The Court’s concerns, rather, were to prevent either the power of government or the foibles of politicians from unduly interfering in man’s reach for the Almighty. Or, at least, that’s how they interpreted the Framers’ concerns as expressed in the First Amendment, applicable to the states via the Fourteenth.

The Abington decision included a little checklist by which interested parties could determine whether or not something violated the “establishment” clause or the “free exercise” clause of the First Amendment. That checklist was improved less than a decade later when the Court heard Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971).

Which is where we are now.

As of 1969, both Pennsylvania and Rhode Island had lots of private schools, the vast majority of which were Roman Catholic. Then, as now, most private schools operated on tight budgets. The average per-pupil expenditure was lower than in public schools in the same area – even when numbers were adjusted to reflect only “secular education.”

In other words, students in private Catholic schools weren’t benefitting from the same resources as kids in public schools, even when learning science, math, or other non-religious subjects.

Both states passed legislation furnishing supplemental support for these private schools, provided the extra funds were used only for the teaching of secular subjects and buying non-religious materials. In some cases this included helping with teacher salaries.

In both states, some parents complained that this diverted resources from public schools to support sectarian institutions, thus violating the First Amendment.

Only a few years before, the Court had determined in Board of Education v. Allen (1968) that it was acceptable for New York to provide textbooks free of charge to all secondary students (Grades 7 – 12), including those in private schools. Surely, Rhode Island and Pennsylvania reasoned, this was essentially the same sort of non-sectarian support.

It was an interesting question. Is modest financial assistance for a sectarian school more like pushing a little prayer and some Bible verses in Engel or Abington, or supplying bus fare and textbooks as in Everson or Allen? Does state assistance constitute “establishment,” or would eliminating that help violate “free exercise”?

Spoiler Alert: the Court decided almost unanimously that it was the former. The help to Catholic schools was a big Constitutional “no-no.”

The conclusion was far from foregone, however. Lemon came hot-on-the-heels of Walz v. Tax Commission of the City of New York (1970) in which the result had been quite different. Walz wasn’t a public school case, but many of the issues were similar.

The city of New York granted property tax exemptions to religious organizations if the property in question was used exclusively for religious worship – putting them in the same category as schools or charities. Some property owners who did pay taxes argued this violated the Establishment Clause.

The Court determined that while government certainly had no business promoting religion, these tax exemptions didn’t actually do that – not quite. They merely allowed the “free exercise” of groups serving the public good, without the same taxes levied on for-profits. They weren’t “establishing,” the Court said – they were stepping back and letting faithy people do faithy stuff.

The Court determined that while government certainly had no business promoting religion, these tax exemptions didn’t actually do that – not quite. They merely allowed the “free exercise” of groups serving the public good, without the same taxes levied on for-profits. They weren’t “establishing,” the Court said – they were stepping back and letting faithy people do faithy stuff.

The majority opinion, written by Chief Justice Warren Burger, cites a number of prior cases by way of illumination – many of them the public school cases we’ve already discussed. At the risk of straying too far from Lemon, he includes a wonderful homage to fallibility and balance worth sharing:

The Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses of the First Amendment are not the most precisely drawn portions of the Constitution. The sweep of the absolute prohibitions in the Religion Clauses may have been calculated, but the purpose was to state an objective, not to write a statute…

I really like that part.

The Court has struggled to find a neutral course between the two Religion Clauses, both of which are cast in absolute terms, and either of which, if expanded to a logical extreme, would tend to clash with the other…

In other words, the Court recognized that the best application of First Amendment values wasn’t necessarily obvious in each and every case. Sometimes, protecting the rights of everyone concerned is an imperfect balancing act.

The First Amendment, however, does not say that, in every and all respects, there shall be a separation of Church and State. We sponsor an attitude on the part of government that shows no partiality to any one group, and that lets each flourish according to the zeal of its adherents and the appeal of its dogma…

The course of constitutional neutrality in this area cannot be an absolutely straight line; rigidity could well defeat the basic purpose of these provisions, which is to insure that no religion be sponsored or favored, none commanded, and none inhibited…

So… we’re faithful to the principles by being flexible with specifics. How pragmatic!

Short of those expressly proscribed governmental acts, there is room for play in the joints productive of a benevolent neutrality which will permit religious exercise to exist without sponsorship and without interference…

There’s “room for play in the joints”? *snort*

It almost seems like Burger wanted to dress up what was in reality a collective, black-robed shrug – a mumble to the effect of “we’re just figuring it out was we go.” Of course, in his defense, the “figuring it out” included 15 pages of detailed analysis, history, and jurisprudence.

We also see a foreshadowing of the following year’s “Lemon Test”:

Determining that the legislative purpose of tax exemption is not aimed at establishing, sponsoring, or supporting religion does not end the inquiry, however. We must also be sure that the end result — the effect — is not an excessive government entanglement with religion. The test is inescapably one of degree. Either course, taxation of churches or exemption, occasions some degree of involvement with religion…

Speaking of Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), we should probably get back to that one – seeing as how it’s in the title of the post and all.

As previously mentioned, both laws – in Rhode Island and in Pennsylvania – were found to be unconstitutional entanglements of the state with religion. As with Walz, Chief Justice Burger wrote the majority opinion.

He again acknowledges the difficulty of neither promoting nor hindering religion, although with much less aplomb than he’d managed the year before.

The language of the Religion Clauses of the First Amendment is, at best, opaque, particularly when compared with other portions of the Amendment…

A law may be one “respecting” the forbidden objective while falling short of its total realization. A law “respecting” the proscribed result, that is, the establishment of religion, is not always easily identifiable as one violative of the Clause. A given law might not establish a state religion, but nevertheless be one “respecting” that end in the sense of being a step that could lead to such establishment, and hence offend the First Amendment.

Yeah, exactly! And also, huh?!

He quickly redeems himself, however, with that surprise judicial hit, “The Lemon Test” – the first of many to come from the Burger Court.

Also, it’s funny to say “Burger Court” and mean something totally for real and serious.

Every analysis in this area must begin with consideration of the cumulative criteria developed by the Court over many years. Three such tests may be gleaned from our cases. First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; second, its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion… finally, the statute must not foster “an excessive government entanglement with religion”…

Or, rephrased to apply more specifically to the case at hand:

In order to determine whether the government entanglement with religion is excessive, we must examine the character and purposes of the institutions that are benefited, the nature of the aid that the State provides, and the resulting relationship between the government and the religious authority…

Justice Burger goes on to explain how very clearly religious these private schools were. Most were located on the same grounds or in close proximity to associated churches. Religious symbols pervaded each campus. Roughly two-thirds of the instructors were nuns.

To cap it all off, the Catholic faith was pretty explicit about the fact that a large part of the reason they had parochial schools to begin with was to spread their faith. So are they religious? Is the Pope Cath-

Um… you probably get the idea.

But what about Allen a few years prior?

In Allen, the Court refused to make assumptions, on a meager record, about the religious content of the textbooks that the State would be asked to provide. We cannot, however, refuse here to recognize that teachers have a substantially different ideological character from books.

Good to know someone realizes that. Can we add “or online courses”?

In terms of potential for involving some aspect of faith or morals in secular subjects, a textbook’s content is ascertainable, but a teacher’s handling of a subject is not. We cannot ignore the danger that a teacher under religious control and discipline poses to the separation of the religious from the purely secular aspects of pre-college education. The conflict of functions inheres in the situation.

You gotta love a phrase like “the conflict of functions inheres in the situation.” And despite several more pages of explanation, that pretty much sums it up. The balance between pushing religion and punishing it is a tricky one, yes – but in this case, the Court decided, the state had some seriously conflicted inhering going on.

It wasn’t malicious. It wasn’t fair to expect teachers to completely separate their spiritual function from their secular labors.

We need not and do not assume that teachers in parochial schools will be guilty of bad faith or any conscious design to evade the limitations imposed by the statute and the First Amendment. We simply recognize that a dedicated religious person, teaching in a school affiliated with his or her faith and operated to inculcate its tenets, will inevitably experience great difficulty in remaining religiously neutral.

Doctrines and faith are not inculcated or advanced by neutrals. With the best of intentions, such a teacher would find it hard to make a total separation between secular teaching and religious doctrine…

Finally, expecting the state to supervise or punish violations of this unattainable “total separation” created the exact sort of entanglement the First Amendment hoped to circumvent. It made the government into the theology police.

To ensure that no trespass occurs, the State has therefore carefully conditioned its aid with pervasive restrictions…

Unlike a book, a teacher cannot be inspected once so as to determine the extent and intent of his or her personal beliefs and subjective acceptance of the limitations imposed by the First Amendment. These prophylactic contacts will involve excessive and enduring entanglement between state and church.

So bus fare and math books are OK. Government-led prayer or devotional readings are not. And, after Lemon, direct support to sectarian schools – under whatever formula – is out as well.

On the other hand, I wish I were young enough to start a band just so I could call it the “Prophylactic Contacts.” But the conflict of functions would probably inhere in my situation.

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – Engel v. Vitale (1962)

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – Everson v. Board of Education (1947)

RELATED POST: Building A Wall of Separation (Faith & School)

After Everson v. Board of Education (1947), fifteen years passed before the next important ‘religion and public schools’ case made its way to the Supreme Court. Whereas Everson dealt with transportation, Engel v. Vitale (1962) addressed the role of the supernatural in the classroom itself.

After Everson v. Board of Education (1947), fifteen years passed before the next important ‘religion and public schools’ case made its way to the Supreme Court. Whereas Everson dealt with transportation, Engel v. Vitale (1962) addressed the role of the supernatural in the classroom itself.

I can’t wait to hear what Governor Fallin and Preston Doerflinger determine about how much tithe God intends for you to pay, and where it should best be applied. And if you argue against them, you’re part of the godless liberalism pervading our once great nation. Good times!

I can’t wait to hear what Governor Fallin and Preston Doerflinger determine about how much tithe God intends for you to pay, and where it should best be applied. And if you argue against them, you’re part of the godless liberalism pervading our once great nation. Good times!