This Is Not About Monkeys

While researching what I hope will be an upcoming book about the “wall of separation” as it relates to public education, I came across as case which has fascinated me far out of proportion to its actual importance. Since I try to keep the published stuff concise and balanced and semi-professional, I’m getting the rest of it out of my system here.

While researching what I hope will be an upcoming book about the “wall of separation” as it relates to public education, I came across as case which has fascinated me far out of proportion to its actual importance. Since I try to keep the published stuff concise and balanced and semi-professional, I’m getting the rest of it out of my system here.

You’re welcome.

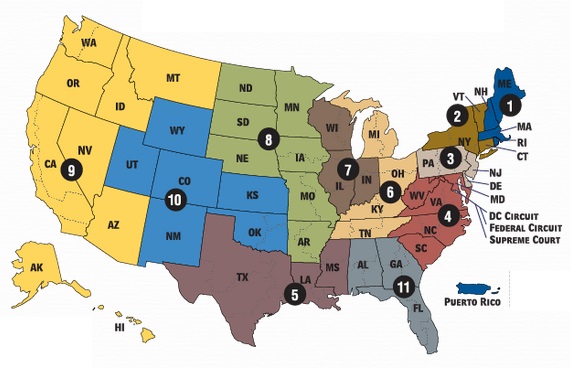

I’ve already written about Mozert v. Hawkins (6th Circuit, 1987) in Part One and Part Two, and fully intend to wrap it up here in this final post – so you can realistically expect Part Four sometime early next week. *sigh*

The Story So Far

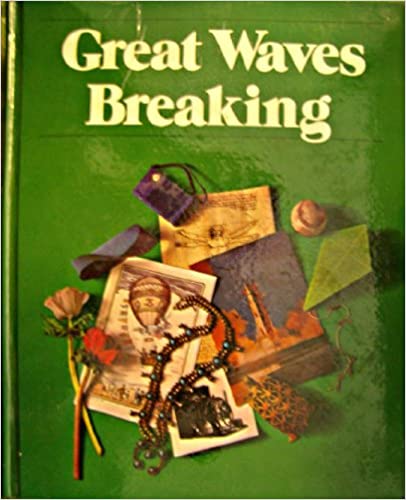

Parents in Hawkins County, Tennessee, led by Vicki Frost, objected to a literature textbook being used in their kids’ public school. The families were fundamentalist Christians, and the stories in the reader were all about imaginary places and events, appreciating different cultures, and asking important questions about what’s truly important – the antithesis of their faith, they insisted. When the school refused to let their kids opt out of using this particular book, they took them to court.

The case began in the Eastern District of Tennessee under Judge Thomas Hull. He rejected a number of their complaints as outside the purview of the federal bench, instead choosing to deal exclusively with the suggestion their free exercise rights were being violated. It didn’t take long – he issued a summary judgement dismissing the case, explaining that there wasn’t enough substance to their complaint to merit a full trial.

The parents appealed to the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals, which suggested maybe Judge Hull should suck it up and give them a real trial because… Issues! Evidence! Hearings! So, back to the ED of TN it went. This time, Judge Hull would find in favor of the parents. He even ordered the school to pay their legal fees. His written opinion is quite… extensive. If members of the bench weren’t totally above such things, one might think he seemed a tad sore about being scolded by his superiors for not taking the case seriously enough. He’d show them time and attention and thought and legal analysis, by golly!

But that, of course, would be ridiculous. He probably just had a lot to say. Fervently.

I’m not going to cover it extensively here, but there are a few highlights which beg for attention. Keep in mind that Hull will be overturned by the 6th Circuit, whose ruling will essentially cite the same reasons he’d given for his summary judgement in the first place – although they’ll say it a bit fancier and with more citations.

Juxtapositions & Implications (Excerpts from Judge Hull)

Judge Hull opens with a basic summary of the case so far, then adds this intriguing commentary:

Judge Hull opens with a basic summary of the case so far, then adds this intriguing commentary:

It is important to note at the outset that the plaintiffs are not requesting that the Holt series be banned from the classroom, nor are they seeking to expunge the theory of evolution from the public school curriculum. Despite considerable fanfare in the press billing this action as “Scopes II.” it bears little relation to the famous “monkey trial” of 1925. These plaintiffs simply claim that they should not be forced to choose between reading books that offend their religious beliefs and foregoing a free public education.

There was fanfare? It seems odd that a federal judge would accuse local media of #fakenews (or at least the 1980s version) in a formal opinion. It’s even odder that anyone would have nicknamed this case “Scopes II,” particularly since that nickname had already been given to an Arkansas case in 1968 – one actually about evolution.

This action juxtaposes two of our most essential constitutional liberties the right of free exercise of religion and the right to be free from a religion established by the state. Moreover, it implicates an important state interest in the education of our children. The education of our citizens is essential to prepare them for effective and intelligent participation in our political system and is essential to the preservation of our freedom and independence.

If you wanted to capture every important element of this case in as few words as possible, you couldn’t do better than that. The “religion clauses,” public education, patriotism, and world citizenship. Add sex and contrived melodrama and you’ve got a mini-series.

From a constitutional standpoint, the most interesting thing was the natural tension which sometimes occurs between free exercise and non-establishment. Socio-emotionally, however, the real hand grenade was the question of individual parental rights (with a side of religious freedom) vs. the presumed long-term good of the child and of society as a whole. Civilization is premised on the idea that we’ll each forego a degree of personal autonomy in order to benefit from participation in society. Schools are a major part of that arrangement.

Public education isn’t primarily intended to be a baby-sitting service, nor should it be overly focused on prepping “meat widgets” for easy plugging into the needs of local employers. Its flavor and mechanics have evolved over the past 250 years, but one thing has remained consistent – at its heart, public education is about trying to build educated, insightful, free men (and later, women) capable of ruling themselves as well as helping to run a rather large republic. Not annoying fundamentalists who find society horrifying to begin with isn’t part of the mission statement, nor should it be.

The Underlying Conflict (It’s Not Between Clauses)

In 1944, the Supreme Court heard Prince v. Massachusetts, one of many Jehovah’s Witnesses cases reaching them in the mid-20th century. This one was a rare loss for the Witnesses. At issue was the question of child labor laws and whether or not parental rights – specifically, their “freedom of religion” – offset or overrode secular statutes designed to protect the child’s welfare. Justice Wiley Rutledge, writing for the majority, penned one of the most succinct and powerful comments in the history of the Court:

In 1944, the Supreme Court heard Prince v. Massachusetts, one of many Jehovah’s Witnesses cases reaching them in the mid-20th century. This one was a rare loss for the Witnesses. At issue was the question of child labor laws and whether or not parental rights – specifically, their “freedom of religion” – offset or overrode secular statutes designed to protect the child’s welfare. Justice Wiley Rutledge, writing for the majority, penned one of the most succinct and powerful comments in the history of the Court:

Parents may be free to become martyrs themselves. But it does not follow they are free, in identical circumstances, to make martyrs of their children before they have reached the age of full and legal discretion when they can make that choice for themselves.

This is a truth which has sadly been largely forgotten as the political weight of various religious groups has expanded substantially in recent decades. Too often, legislatures and courts have opted to allow children to suffer from easily curable illness, die from easily treated maladies, or undergo all varieties of sexual and emotional abuse rather than risking any appearance of “interfering” with “parental rights” or “free exercise of religion.” Little wonder, then, that it’s often difficult for local schools to stand their ground on such matters.

Things weren’t quite so severe in Mozert v. Hawkins, but you can feel the issue writhing throughout the rhetoric as the courts sought to balance parental rights with societal good and a vestigial belief in putting the welfare of the child ahead of the whims of the adult. Should parents have the right to ensure that their child grows up unable and unwilling to interact productively with those outside their bubble? To be taught bogus science and history as fact and intolerance as faith? Where, exactly, is the boundary between freedom of religion and freedom from the social contract on which civilization is built?

We Need A Cool Name

Here’s a cute little bit of trivia which has somehow failed to come up before now:

In September 1983, a group of Hawkins County residents, including most of the plaintiff-parents, formed an organization named Citizens Organized for Better Schools (COBS). Members of COBS spoke at regularly scheduled school board meetings… objecting, among other things, to the use of the Holt series. The COBS members apprised the Board that they found the Holt series offensive to their religious beliefs and presented petitions requesting removal of the Holt series from the schools.

First, “among other things”? There were other things? Try to pretend you’re not dying to know what else they brought up. Go ahead – try!

Second, “COBS”? Their self-selected group name was “COBS”? As in, things we say are up someone’s @$$ when they’re being unreasonably rigid or demanding in their beliefs? It’s not even a great group name spelled out – “Citizens Organized for Better Schools”? Was “Families Asserting Sincere Classroom Involvement Since Textbooks Suck” already taken?

Second, “COBS”? Their self-selected group name was “COBS”? As in, things we say are up someone’s @$$ when they’re being unreasonably rigid or demanding in their beliefs? It’s not even a great group name spelled out – “Citizens Organized for Better Schools”? Was “Families Asserting Sincere Classroom Involvement Since Textbooks Suck” already taken?

You’d think with a little creativity and imagination, they could have—oh, wait… I guess that was the whole point of the lawsuit, wasn’t it?

“When deciding a free exercise claim, the courts apply a two-step analysis. First, it must be determined whether the government action does, in fact, create a burden on the litigant’s exercise of his religion. If such a burden is found, it must then be balanced against the governmental interest, with the government being required to show a compelling reason for its action.”

Notice the issue is not merely whether or not the school’s actions are creating a burden on the parents’ “free exercise.” If it turns out they are, does the government have a sufficiently GOOD REASON for what they’re doing? The right to free exercise is not absolute. It should be weighed against the public good (see above).

In addition, it must be determined whether the state has acted in a way which constitutes “the least restrictive means of achieving {the} compelling state interest,” as measured by its impact upon the plaintiffs. (Thomas v. Review Board, 1981).

So there were three basic questions. (1) Is free exercise being violated? (2) If so, is it for a valid reason? (3) If it is a valid reason, are there less-violative ways the state could accomplish the same thing?

How Violative You Wanna Be Today?

It appears to the Court that many of the objectionable passages in the Holt books would be rendered inoffensive, or less offensive, in a more balanced context. The problem with the Holt series, as it relates to the plaintiffs’ beliefs, is one of degree. One story reinforces and builds upon the others throughout the individual texts and the series as a whole. The plaintiffs believe that, after reading the entire Holt series, a child might adopt the views of a feminist, a humanist, a pacifist, an anti-Christian, a vegetarian, or an advocate of a “one-world government.”

This is a valid concern. Still, I wonder how differently things would have gone if the parents had pushed for the addition of more acceptable materials rather than the removal of those already there – a “the solution to offensive free speech is more and better free speech” approach. Of course, this is just some amateur Monday morning quarter-parenting.

Plaintiffs sincerely believe that the repetitive affirmation of these philosophical viewpoints is repulsive to the Christian faith so repulsive that they must not allow their children to be exposed to the Holt series. This is their religious belief. They have drawn a line, “and it is not for us to say that the line {they} drew was an unreasonable one.” (Thomas)

That’s true inasmuch as judging the belief itself. The government has no business worrying about the validity of specific convictions or doctrines. That doesn’t mean the rest of society has to cooperate with such beliefs, however.

That’s true inasmuch as judging the belief itself. The government has no business worrying about the validity of specific convictions or doctrines. That doesn’t mean the rest of society has to cooperate with such beliefs, however.

Judge Hull goes on to find that the parents’ free exercise rights have clearly been burdened (something the district didn’t put much energy into contesting). The real question, then, was whether or not the school had dug in on the textbook thing as the “least restrictive means of achieving some compelling state interest.” In other words, were there ways to accomplish the same, valid state goal of educating children without forcing this particular issue with this particular textbook?

Compromises, Restrictions, & Sneaky Stuff Educators Do

Schools make these compromises all the time. The less you hear about them in the local news, the more successful they’ve been. “Professional Development” days for teachers just happen to fall on MLK Day or Good Friday. The transgender kid is given permission to use faculty restrooms so they avoid the spotlight and the school avoids an uncomfortable showdown. Teachers work out alternate arrangements with students over potentially problematic material in ways that make the family feel listened to but don’t require an unreasonable degree of additional preparation on the part of the teacher or other staff.

It’s not always possible, but it’s far more common than those outside the system probably realize. I’d even wager that somewhere in your kids’ school, teachers are having subtle conversations about Jesus or sexuality or drugs or other personal choices – not because they’re trying to manipulate your children behind your back or because they fear neither god nor the legal system, but because they care about young people. Kids come to us with all sorts of things they’re trying to process. Most of the time we’re not interested in telling them what to do so much as validating their concerns and their feelings and their confusion, then trying to nudge them away from doing stupid make-things-much-worse stuff. Sure, we could pick up the phone and start screaming “YOUR CHILD IS KINDA GAY NOW; GRAB THE CAR BATTERY AND CALL THE CONVERSION CAMP!” Maybe that’s even the professionally safe, legal thing to do.

But, you know – &#$% that.

Most teachers aren’t interested in openly opposing parents or anyone else. We’re just trying to teach a little history or math or whatever. But most of us also won’t go out of our way to add to a kids’ problems if we can avoid it. I realize it drives conservatives crazy to hear this, but at times your suspicions are correct – there are those of us periodically trying to figure out a legal, non-fireable way to do what’s best for your kids. There’s often an unpleasant dissonance, however, between what’s desperately needed by that young person in front of us with no one else to turn to and what’s dictated by cover-your-ass policies. I can shift the conversation back to those multiple choice questions they missed or write them a pass to the school counselor who doesn’t know them from Salvatore Perrone and have a much better chance of keeping my job, but I’ll probably go to Teacher Hell by way of tradeoff.

Most teachers aren’t interested in openly opposing parents or anyone else. We’re just trying to teach a little history or math or whatever. But most of us also won’t go out of our way to add to a kids’ problems if we can avoid it. I realize it drives conservatives crazy to hear this, but at times your suspicions are correct – there are those of us periodically trying to figure out a legal, non-fireable way to do what’s best for your kids. There’s often an unpleasant dissonance, however, between what’s desperately needed by that young person in front of us with no one else to turn to and what’s dictated by cover-your-ass policies. I can shift the conversation back to those multiple choice questions they missed or write them a pass to the school counselor who doesn’t know them from Salvatore Perrone and have a much better chance of keeping my job, but I’ll probably go to Teacher Hell by way of tradeoff.

None of which is, um, probably the fault of Vicki Frost or the COBS – although the issues themselves are somewhat related. It’s also possible I’ve just uncovered the underlying reason for my fascination with this case, along with some uncomfortable realizations about a few of my own personal and professional issues.

*pause*

The point is, our primary job isn’t to make parents happy. It’s to do what’s best for kids and the society in which they’ll live – within the structure and limits of the gig, of course. I was, um… just kidding about that “my first thought isn’t always to out the kid to dad” stuff. I totally do. Every time. I’ll even bring the car battery.

The Decision in Tennessee

Here’s the crux of Judge Hull’s decision:

{T}he state, acting through its local school board, has chosen to further its legitimate and overriding interest in public education by mandating the use of a single basic reading series. The Court has found that compulsory use of this reading series burdens the plaintiffs’ free exercise rights. In order to justify this burden, the defendants must show that the state’s interest in the education of its children necessitates the uniform use of the Holt reading series that this uniformity is essential to accomplishing the state’s goals. Therefore, the Court must decide whether the state can achieve literacy and good citizenship for all students without forcing them to read the Holt series.

Well, if you frame it that way, it’s pretty clear what the court’s answer is going to be…

It seems obvious that this question must be answered in the affirmative. The legislative enactments of this state admit as much. Although Tennessee has manifested its compelling interest in education through its compulsory education law, it has, by allowing children to attend private schools or to be taught at home, also acknowledged that its interests may be accomplished in other ways and may yield to the parental interest in a child’s upbringing. Moreover, the fact that the state has approved several basic reading series for use in the Tennessee public schools tells us something of the expendability of any particular series.

In defense of the district, they weren’t saying that the only way children in the state of Tennessee could be properly educated was to read this textbook. They were arguing that teachers can’t realistically teach a room of 30 kids effectively if they let everyone customize the curriculum as they see fit. We talk a good game about “individualized instruction,” and we do our best to tweak it when we can. But public education only works on the budget it does because of economies of scale.

We can leave off the onions or upsize the fries, but if it’s burger day, we’re doing burgers. Nevertheless, the parents in this case had successfully framed their case as a “hold the onions” issue, while the schools were arguing they couldn’t become Cheesecake Factory and offer every parent a full menu. As a result…

It is true that many of the plaintiffs’ objections suggest that other elements of the curriculum besides the reading program could easily be considered offensive to their beliefs. However… {they} have not made multi-subject, multi-text objections; they have objected to the Holt reading series. The defendants may not justify burdening the plaintiffs’ free exercise rights in this narrow case on the basis of what the plaintiffs might find objectionable in the future.

Well-played, Team COBS. Besides, there was one last strategic error on the part of the school which sealed their fate – at least until appeal.

Moreover, proof at trial demonstrated that accommodating the plaintiffs is possible without materially and substantially disrupting the educational process… The students at the middle school were provided with analternative reading arrangement for a period of several weeks. There was no testimony at trial that those arrangements resulted in any detriment to the student-plaintiffs. In fact, those children still received above average grades for that period. Even after the School Board mandate, compromise arrangements were worked out with some of the plaintiffs.

The danger in bending over backwards to accommodate parents or students is that once you’ve established that precedent, there’s no telling what you’ll be expected to do moving forward. Worse, teachers and administrators sound like complete tools whenever they express this up front.

The danger in bending over backwards to accommodate parents or students is that once you’ve established that precedent, there’s no telling what you’ll be expected to do moving forward. Worse, teachers and administrators sound like complete tools whenever they express this up front.

That doesn’t mean they’re wrong.

The Solution

Under these circumstances, the Court finds that a reasonable alternative which could accommodate the plaintiffs’ religious beliefs, effectuate the state’s interest in education, and avoid Establishment Clause problems, would be to allow the plaintiff-students to opt out of the school district’s reading program. The State of Tennessee has provided a complete opt-out, a total curriculum alternative, in its home schooling statute… Although it will require extra effort on the part of the plaintiff-parents, these parents have demonstrated their willingness to make such an effort as the price of accommodation in the public school system.

Damn – who saw THAT coming? “Since the parents won’t bend and the school is acting like making adjustments would be such a burden, how ‘bout we just let these kids learn to read at home?”

To make it more palatable, Judge Hull ordered the district to pay the parents a bunch of money for their trouble.

Mozert v. Hawkins will make one final stop at the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals. They’ll throw in a few even more interesting details before making their final decision. We’ll talk about that next time.

This is an important distinction. The parents weren’t trying to get their own materials or beliefs injected INTO the curriculum; they were merely trying to allow their own children to opt OUT of the existing materials because they found them offensive. This sets the issue apart from issues like school prayer or creationism, in that they’re not apparently interested in pressuring other children into conforming to their religious druthers. If there were, the case would be far simpler. It might even have justified the way the judge in Tennessee completely blew them off and no-wonder-he’ll-never-reach-the-circuit-courts-like-us.

This is an important distinction. The parents weren’t trying to get their own materials or beliefs injected INTO the curriculum; they were merely trying to allow their own children to opt OUT of the existing materials because they found them offensive. This sets the issue apart from issues like school prayer or creationism, in that they’re not apparently interested in pressuring other children into conforming to their religious druthers. If there were, the case would be far simpler. It might even have justified the way the judge in Tennessee completely blew them off and no-wonder-he’ll-never-reach-the-circuit-courts-like-us. While the general idea of the Superintendent’s complaint is no doubt spot on, I have to wonder why his team didn’t lead with what to me is the much more palatable argument. “We WANT our kids to be exposed to a variety of ideas and beliefs. We’re not telling them what to believe; we’re trying to help them understand how other people think and feel – the essential foundation of all civilization. While the mechanics of grammar and structure may be the foundation of reading instruction, empathy is the heart and soul of all good literature. Teaching them that they don’t have to even be in the room anytime someone around them veers into non-fundamentalism isn’t freedom of religion – it’s freedom from thought, challenge, or diversity. It’s a violation of our ethical and professional obligation to prepare them to function in the real world – socially, professionally, and politically.”

While the general idea of the Superintendent’s complaint is no doubt spot on, I have to wonder why his team didn’t lead with what to me is the much more palatable argument. “We WANT our kids to be exposed to a variety of ideas and beliefs. We’re not telling them what to believe; we’re trying to help them understand how other people think and feel – the essential foundation of all civilization. While the mechanics of grammar and structure may be the foundation of reading instruction, empathy is the heart and soul of all good literature. Teaching them that they don’t have to even be in the room anytime someone around them veers into non-fundamentalism isn’t freedom of religion – it’s freedom from thought, challenge, or diversity. It’s a violation of our ethical and professional obligation to prepare them to function in the real world – socially, professionally, and politically.” By way of driving their point home, those sneaky fundies had somehow secured a copy of the Teacher’s Edition of the textbook in question – which, for those of you outside the world of public education, is akin to nabbing the Ark of the Covenant from Indiana Jones or remotely hacking celebrity cell phones in order to post their dirty selfies online. The Court explains:

By way of driving their point home, those sneaky fundies had somehow secured a copy of the Teacher’s Edition of the textbook in question – which, for those of you outside the world of public education, is akin to nabbing the Ark of the Covenant from Indiana Jones or remotely hacking celebrity cell phones in order to post their dirty selfies online. The Court explains: Judge Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee would do just that. As instructed, he’d give the fundamentalists a fuller hearing and – hold on to your powdered wigs – decide that maybe they had a point after all. The first time through, he’d found that because the textbook and the school were entirely neutral towards religion in general or specific religions in particular, there was no First Amendment violation. The second time around (fresh from his scolding by the 6th Circuit), Hull found in favor of the parents and even fined the school district to pay for their legal expenses.

Judge Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee would do just that. As instructed, he’d give the fundamentalists a fuller hearing and – hold on to your powdered wigs – decide that maybe they had a point after all. The first time through, he’d found that because the textbook and the school were entirely neutral towards religion in general or specific religions in particular, there was no First Amendment violation. The second time around (fresh from his scolding by the 6th Circuit), Hull found in favor of the parents and even fined the school district to pay for their legal expenses.

1. After it became clear that state-sponsored prayer was no longer a realistic option in public education, states began experimenting with the idea of a “moment of silence” during which students could pray (although no one had ever suggested that they couldn’t).

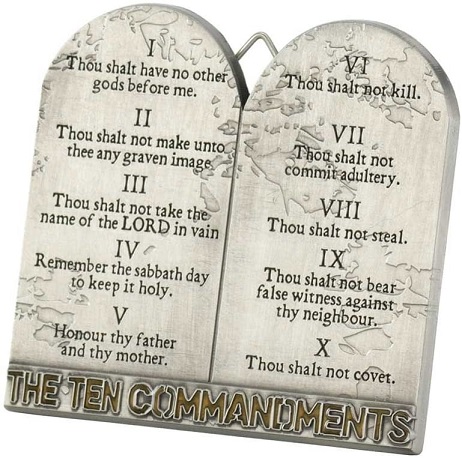

1. After it became clear that state-sponsored prayer was no longer a realistic option in public education, states began experimenting with the idea of a “moment of silence” during which students could pray (although no one had ever suggested that they couldn’t). The Supreme Court’s decision in Stone v. Graham was announced on November 17th, 1980. Less than two weeks earlier, Ronald Reagan had been elected President of the United States, initiating what would later be called the “Reagan Revolution” – a resurgence of conservative values and policies anchored in an idealized past. The events leading to Stone began years earlier, but its outcome sent a message to the faithful in the 1980s similar to that of Engel v. Vitale and Abington v. Schempp two decades before: American’s fundamental values (meaning public promotion of Christianity) were under attack by intellectual elitists… aka “liberals.” And some of them wore robes.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Stone v. Graham was announced on November 17th, 1980. Less than two weeks earlier, Ronald Reagan had been elected President of the United States, initiating what would later be called the “Reagan Revolution” – a resurgence of conservative values and policies anchored in an idealized past. The events leading to Stone began years earlier, but its outcome sent a message to the faithful in the 1980s similar to that of Engel v. Vitale and Abington v. Schempp two decades before: American’s fundamental values (meaning public promotion of Christianity) were under attack by intellectual elitists… aka “liberals.” And some of them wore robes.