A few days ago, Peter Greene at Curmudgucation wrote about a Physical Education teacher named Tanner Cross who was suspended for refusing to refer to transgender students by their preferred pronouns. I wholeheartedly agreed with everything Greene write about the situation and intended to tweet it a few times then leave it alone.

A few days ago, Peter Greene at Curmudgucation wrote about a Physical Education teacher named Tanner Cross who was suspended for refusing to refer to transgender students by their preferred pronouns. I wholeheartedly agreed with everything Greene write about the situation and intended to tweet it a few times then leave it alone.

But it’s bugging me. The whole situation. The claims being made – especially the moral indignation of this public school teacher demanding the right to assert his personal religious beliefs in class.

Because that’s not how public school works.

There are a number of factors making this more complicated than it might otherwise be. The first is that Cross’s suspension came after he objected to the policy at a school board meeting and announced that he’d never “affirm that a biological boy can be a girl, and vice versa.” He equated using transgender teens’ preferred pronouns to “lying to a child” and “abuse {of} a child” before adding that it was also “sinning against our God.”

A few days later, Cross was suspended and – because school districts are pretty much required to dramatically overreact in every possible conflict – banned from campus, prohibited from attending school events, and essentially treated as if he’d already mowed down a half-dozen LGBTQ+ kids with his church-issued AK-47.

He hadn’t.

The policy wasn’t even finalized yet, let alone implemented. Presumably, the Board was taking comments on the thing when Cross spoke. There’s no indication in the stories I found that he jumped up in the middle of unrelated business and began ranting unexpectedly. I think his position is inane and unethical (more on that in a bit) but based on the information available it seems to me the district might have flipped the panic switch a bit prematurely.

I mean, can you even violate a policy that hasn’t been instituted yet?

But here’s the bigger problem. The swell of right-wing support rallying behind Cross for sticking it to them transgender kids and all their liberal nonsense about “gender identity” are taking the position that as a teacher in a public school he has freedom of both speech and religion, as if he can say and do whatever he likes in this role thanks to the First Amendment.

That’s not how it works.

On the one hand, the Supreme Court made it very clear a half-century ago in Tinker v. Des Moines (1969) that

First Amendment rights, applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment, are available to teachers and students. It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.

This right is not absolute, however. Most of the cases I examined for “Have To” History: A Wall of Education (insert book promo here) which involved public funding being used to push religious beliefs involved “school choice” programs – taxpayer funded private schools indoctrinating students with their own versions of history, science, etc. The few “teacher free speech” cases involving public schools were mostly situations in which a teacher wished to teach creationism as being scientifically comparable to evolution scientifically, despite district curriculum policies to the contrary.

None of these teachers won. Evolution is (so far) a scientifically accepted theory of man’s development; Intelligent Design is an effort to replace evolution with unsupported religious beliefs. God may have created the universe, but to date that reality has to be accepted on faith.

Teacher’s aren’t allowed to attack students for their beliefs or push their own faiths on students. I’d never kneel or protest during the Pledge of Allegiance during First Period because I’m not there as Blue Cereal flinging liberal pith everywhere; I’m there as an employee and representative of the state and school system, and they want to do the Pledge. When I didn’t like military recruiters coming to my school, I took it up with my administration privately. (If they’d asked me to fire a weapon on the other hand, I might have refused. Perhaps Mr. Cross would see that as comparable?)

I’ve had kids who loved Donald Trump. I might needle them a bit, but I’d never intentionally risk my connection with them by challenging their passion the way I might with other adults. I had a kid a few years back who repeatedly wore a shirt with Trump heavily armed and riding a T-Rex and who always made sure I noticed. We laughed about it, but I promise you that kid knew I loved and accepted him just the same.

Obviously the same thing is true for my gay kids, my Muslim kids, my atheists, my Mormons, or whatever. I’ve only had a few transgender students, and I try to show them the same love and respect as well. This isn’t something heroic on my part; it’s true of almost every teacher I know with every kid. It’s the norm. It’s how school is supposed to work.

Now, here’s something I don’t usually bring up. If I’m being honest, I don’t fully understand the whole transgender thing. I can’t quite get my head around it the way I’ve managed to do with race, religion, homosexuality, or whatever.

I share this not because I want to argue with anyone about it, but because the whole point is that I don’t need to “understand” or even “accept” it (let alone “approve” of anything) when it comes to my kids. My job is to teach them English and History and to treat them with respect and decency while I do it. I want to help them think, and yes – I sometimes care a little about all their weird personal drama, but only because (a) it tends to interfere with their ability to care deeply about appositives, and (b) I want them to feel validated and supported as human beings whenever possible.

What I’m not there to do is take a stand on my progressive ideals. The nice preacher’s wife next door to me feels the same way about her very conservative Christianity. Her faith is everything to her, but she doesn’t talk about it with kids unless they ask, and then only in the right circumstances. She wants to make sure nothing she says leaves anyone feeling “otherized” or degraded. That is, in fact, central to her faith.

I know, right?

Teenagers are a sensitive, melodramatic bunch. It doesn’t take that much for them to feel marginalized – particularly if they belong to a group which is already kicked around and rejected, sometimes by their own families.

I said above that there were too many things in this case which complicate it, and I worry they’re going to be completely overlooked by the majority of people who end up taking very dramatic stands about it as things progress. Here are the last two I’ll be ranting about today.

Mr. Cross insists that using the preferred pronouns of transgender kids is against his religion. I’m curious what religion that might be. I like the way Greene covered this part in his post:

Exactly which part of the Christian faith, which teaching of Jesus, requires people of faith to object to trans folks? Cross (and his attorneys) are trying to hedge bets by suggesting the problem is the lying, that telling anything but the unvarnished truth is unChristian. I’m…. dubious. Cross teaches elementary school; I’d like to be there for the days when he blasts kindergartners for talking about Santa, the Tooth Fairy, or the Easter Bunny…

The courts, however, do not look to the validity or accuracy of a theological position. At best, they consider sincerity (does the person really believe this, or is it being used as an excuse for their behavior?) No judge worth his gavel will decide this one based on the complete lack of New Testament mandates regarding pronoun usage.

What I hope the courts will consider is the difference between religious or political speech outside of school hours (which is sometimes protected, although not always) and “I refuse to demonstrate this form of decency and acceptance to trans students specifically because they are going to hell for their perversion and lies.”

Which brings me to the last messy bit of this whole situation. Because Mr. Cross was suspended before the policy was even implemented, I’m curious what his solution in class with real students might have been (or might be, since he’s apparently been reinstated via court order). In my mind, the answer matters.

Despite my hyperbole, I have no reason to think he intends to go full Santa Fe ISD and berate his kids for being hell-bound. If he did, I’d like to think the courts would refuse to categorize that as protected free speech or free exercise of his religion. But what if he defied the policy by always using the child’s name instead of what he believes to be the “correct” pronoun? Or what about using “they” instead of “he” or “she”? Are evolving grammatical norms the same sort of violation of his faith as, say… “lying”?

I’m not saying he shouldn’t still be held accountable for defying the policy, but morally and professionally, that would be a very different sort of violation, wouldn’t it?

Left unaddressed in the coverage of the case so far is the question of whether the transgender students of Loudon County, Virginia, have expressed any sort of preference themselves about how this could or should behandled. Is this policy an effort to respond to their concerns, or has someone been feeling all “woke” lately and decided to straight-white-savior everyone based on their enlightened Twitter feed? I’d like to assume the best, but…

Despite my own ambiguity about some transgender issues, I’m having a hard time sympathizing with Mr. Cross on this one. My inclination is to defend the kids and err on the side of acceptance, respect, and support. When conflicts like this erupt, the people most impacted tend to be the group already marginalized and mistreated to begin with, and this case has the potential to be a complete mess with plenty of point-missing and grandstanding from all sides.

I hope both parties surprise me and find a decent compromise before things escalate further. We’ll see.

There are certainly plenty of wonderful individual people of faith around, including many Christians.

There are certainly plenty of wonderful individual people of faith around, including many Christians. Notice the title – the “Star Spangled Banner Protection Act.” Because patriotism, like faith, apparently can’t survive without government propping it up by force. Note also the claim that American soldiers fight and die “for our flag.” Not our values, not our Constitution, and certainly not our people – for the cloth and the symbols and the rituals.

Notice the title – the “Star Spangled Banner Protection Act.” Because patriotism, like faith, apparently can’t survive without government propping it up by force. Note also the claim that American soldiers fight and die “for our flag.” Not our values, not our Constitution, and certainly not our people – for the cloth and the symbols and the rituals. The same basic approach was taken by

The same basic approach was taken by  In other words, the only reason to pass these laws is because those supporting them believe they ARE statements of faith. They DO matter in distinguishing America’s official religion (which they’re willing to pretend isn’t official in order to secure it as such) from all of those other belief systems (which have no place in public schools because of the First Amendment).

In other words, the only reason to pass these laws is because those supporting them believe they ARE statements of faith. They DO matter in distinguishing America’s official religion (which they’re willing to pretend isn’t official in order to secure it as such) from all of those other belief systems (which have no place in public schools because of the First Amendment).

While it was not always mentioned by name, several major decisions of the Court in the early 21st century very much involved the history and potential future of the “Blaine Amendment.” Blaine is a general label applied to various provisions in 37 different state constitutions limiting or prohibiting the use of state funds to support religious organizations or sectarian activity. The precise wording and application vary from state to state, and 13 states don’t have one at all. Most Blaine Amendments are actually sections or clauses in their respective state constitutions and not “amendments” at all, but the term has proven persistent. Plus, it’s used in the singular (collectively) or plural more or less interchangeably – so that’s kinda fun.

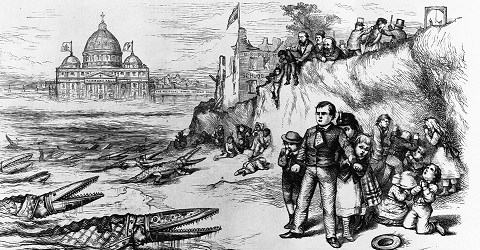

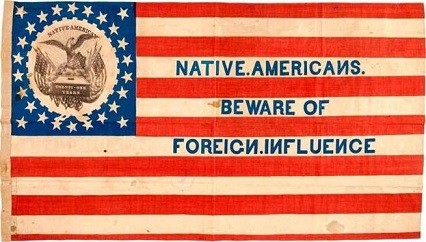

While it was not always mentioned by name, several major decisions of the Court in the early 21st century very much involved the history and potential future of the “Blaine Amendment.” Blaine is a general label applied to various provisions in 37 different state constitutions limiting or prohibiting the use of state funds to support religious organizations or sectarian activity. The precise wording and application vary from state to state, and 13 states don’t have one at all. Most Blaine Amendments are actually sections or clauses in their respective state constitutions and not “amendments” at all, but the term has proven persistent. Plus, it’s used in the singular (collectively) or plural more or less interchangeably – so that’s kinda fun. The Know-Nothings, who actually called themselves “The American Party,” were the MAGA of their day – slogan driven, easily triggered, and fiercely patriotic (as long as the nation they perpetually celebrated prioritized those who looked and thought as they did). They didn’t have a “dark web” or the chance to go giddy over secret Q-Anon symbols encoded in the evening news, but they did their best to be melodramatic nonetheless. When asked about their political druthers or anything related to the party itself, members were expected to go full Sgt. Schultz and claim to “know nothing” – hence the nickname.

The Know-Nothings, who actually called themselves “The American Party,” were the MAGA of their day – slogan driven, easily triggered, and fiercely patriotic (as long as the nation they perpetually celebrated prioritized those who looked and thought as they did). They didn’t have a “dark web” or the chance to go giddy over secret Q-Anon symbols encoded in the evening news, but they did their best to be melodramatic nonetheless. When asked about their political druthers or anything related to the party itself, members were expected to go full Sgt. Schultz and claim to “know nothing” – hence the nickname. More recently, in 2018, the Supreme Court upheld then-President Trump’s “Muslim Ban” on travel from a half-dozen countries. Trump had promised a “Muslim Ban,” his agents fought for a “Muslim Ban,” and his supporters celebrated the proclamation of a “Muslim Ban” because it was about time we started banning those Muslims with a Muslim Ban that bans them darned Muslims! After backlash from the courts, however, the administration managed to tweak the language enough that it could conceivably be viewed by someone who’d missed all the kerfuffle as a valid national security measure that only coincidentally sorta looked a great deal like a Muslim Ban. (It probably helped that they crossed out the title “Muslim Ban” at the top and scribbled “Valid National Security Measure” in orange crayon.) It was this “Huh? A ‘Muslim Ban’? Who told you THAT?” version the Supreme Court chose to validate, treating the act’s obvious intent and recent history like mysteries lost to the ages and certainly of no relevance to this shiny new valid security measure before them.

More recently, in 2018, the Supreme Court upheld then-President Trump’s “Muslim Ban” on travel from a half-dozen countries. Trump had promised a “Muslim Ban,” his agents fought for a “Muslim Ban,” and his supporters celebrated the proclamation of a “Muslim Ban” because it was about time we started banning those Muslims with a Muslim Ban that bans them darned Muslims! After backlash from the courts, however, the administration managed to tweak the language enough that it could conceivably be viewed by someone who’d missed all the kerfuffle as a valid national security measure that only coincidentally sorta looked a great deal like a Muslim Ban. (It probably helped that they crossed out the title “Muslim Ban” at the top and scribbled “Valid National Security Measure” in orange crayon.) It was this “Huh? A ‘Muslim Ban’? Who told you THAT?” version the Supreme Court chose to validate, treating the act’s obvious intent and recent history like mysteries lost to the ages and certainly of no relevance to this shiny new valid security measure before them. Then, in 2017, a particularly conservative Court decided that the whole “wall of separation” thing was overblown. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017), the Court ruled that if the state was going to offer ANY public institutions financial support – in this case, new bouncy rubber “gravel” for their playgrounds – it had to include religious institutions in the mix no matter what the state constitution might say or the original program intend. Hence Trinity Lutheran, an overtly religious institution which proudly proclaimed that everything it did and every facility under its control was there to bring little children to Jesus, would receive the same check directly out of state funds as the public school playground down the street which was just there so kids had a safe place to play – or perhaps instead of it. Blaine was now clearly on life support but still taking up bed space.

Then, in 2017, a particularly conservative Court decided that the whole “wall of separation” thing was overblown. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017), the Court ruled that if the state was going to offer ANY public institutions financial support – in this case, new bouncy rubber “gravel” for their playgrounds – it had to include religious institutions in the mix no matter what the state constitution might say or the original program intend. Hence Trinity Lutheran, an overtly religious institution which proudly proclaimed that everything it did and every facility under its control was there to bring little children to Jesus, would receive the same check directly out of state funds as the public school playground down the street which was just there so kids had a safe place to play – or perhaps instead of it. Blaine was now clearly on life support but still taking up bed space.

I’m working on a follow-up to

I’m working on a follow-up to