Free Exercise Trumps “No Establishment”

If you’re looking for a fairly balanced overview of this case, I suggest starting here. If you’re looking for pithy, insightful analysis, on the other hand, you’re in the right place. The second part of it, anyway.

Last time, we got through opening remarks and personal disclaimers, gave a little background on the Amendments involved, and covered the Court’s introduction to the facts of the case. Chief Justice Roberts summarized the lower courts’ decisions to side with the state. Basically, they’d reasoned, Maine’s plan was intended to offer a proxy of sorts for traditional public education, and thus it was perfectly constitutional to exclude religious schools from the program.

Here’s how the Chief Justice and his cabal respond:

The Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment protects against “indirect coercion or penalties on the free exercise of religion, not just outright prohibitions” (Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Assn., 1988). In particular, we have repeatedly held that a State violates the Free Exercise Clause when it excludes religious observers from otherwise available public benefits. (See Sherbert v. Verner, 1963…; see also Everson v. Board of Ed. of Ewing, 1947…) A State may not withhold unemployment benefits, for instance, on the ground that an individual lost his job for refusing to abandon the dictates of his faith…

He then recaps Trinity Lutheran v. Comer (2017) and Espinoza v. Montana (2020) by way of demonstrating the Court’s recent fondness for free exercise, even when it means state funding of religious organizations.

The “unremarkable” principles applied in Trinity Lutheran and Espinoza suffice to resolve this case. Maine offers its citizens a benefit: tuition assistance payments for any family whose school district does not provide a public secondary school. Just like the wide range of nonprofit organizations eligible to receive playground resurfacing grants in Trinity Lutheran, a wide range of private schools are eligible to receive Maine tuition assistance payments here. And like the daycare center in Trinity Lutheran, BCS and Temple Academy are disqualified from this generally available benefit “solely because of their religious character.” By “conditioning the availability of benefits” in that manner, Maine’s tuition assistance program – like the program in Trinity Lutheran – “effectively penalizes the free exercise” of religion.

Roberts acknowledges that there are times when a state may be justified in excluding religious organizations from general laws or benefits, but that “this is not one of them.” For good measure, he brings in the issue of “parent choice” from one of the “voucher”-style cases the Court has tackled in recent decades.

As noted, a neutral benefit program in which public funds flow to religious organizations through the independent choices of private benefit recipients does not offend the Establishment Clause. (See Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 2002.) Maine’s decision to continue excluding religious schools from its tuition assistance program after Zelman thus promotes stricter separation of church and state than the Federal Constitution requires…

But as we explained in both Trinity Lutheran and Espinoza, such an “interest in separating church and state ‘more fiercely’ than the Federal Constitution . . . ‘cannot qualify as compelling’ in the face of the infringement of free exercise.” … Justice Breyer stresses the importance of “government neutrality” when it comes to religious matters, but there is nothing neutral about Maine’s program. The State pays tuition for certain students at private schools – so long as the schools are not religious. That is discrimination against religion. A State’s antiestablishment interest does not justify enactments that exclude some members of the community from an otherwise generally available public benefit because of their religious exercise.

That’s the part that’s going to bust open the dam sooner rather than later. In and of itself, it’s entirely reasonable and constitutionally sound. As far back as Everson v. Board of Education (1947) when the state of New Jersey reimbursed parents for bus fare as part of helping their kids get to school, the Court has been fine with a “general benefit” that just happens to benefit religious organizations as well. The city repairs roads which help people get to church. The police (theoretically) protect the faithful from bad guys while they pray, chant, or sing. Fire departments respond if a mosque or temple is ablaze. The Court insists this is the same basic thing.

Except that it’s not.

General Benefits vs. Funding Indoctrination

Enabling an institution to do whatever it does by providing public services is as neutral as government can get. Those road crews don’t jump in and do repairs on the sanctuary or mosque as part of their job because that would be “establishment” – active support of specific religious activities or institutions. For them to avoid maintaining any streets which pass near a church, however, would be to deny “free exercise” – actively making it difficult for believers to partake in whatever partakery is at hand.

What the Court has done in Carson v. Makin is a substantial step further. They’ve demanded that states providing any sort of choice or flexibility in their school systems must offer comparable support for religious indoctrination in place of some of that education. They’re requiring tax dollars designated for preparing young people to function competently in a modern, diverse, complex world, be redirected to teach homophobia, science denial, sexism, misogyny, alternative history, or whatever else might be trending that week in right-wing curriculums.

A Catholic hospital is primarily a hospital; it simply happens to have a lot of Catholics working there and easy access to clergy should one be so inclined. It is unlikely, however, that the medical care itself will be substantially altered by the theology of those in charge. (I realize there are some exceptions – particularly when it comes to reproductive rights – but I’m speaking in general terms.) When Medicare reimburses the hospital for medical services provided to qualified patients, the government is playing nicely with religion. It’s neither promoting Catholicism in any meaningful way nor excluding otherwise qualified health care professionals based on their beliefs.

You’ll notice, however, that there aren’t many hospitals run by the Jehovah’s Witnesses or Buddhists. Imagine that there were, and that you were rushed into the ER at either one after a serious accident. The JWs would no doubt do their best to care for you, but they don’t believe in blood transfusions, so… bad luck, there. The Buddhists believe that suffering is part of life and must be met with acceptance rather than complicated with medical technology and all that rushing around and beeping. Now imagine that the Court has just determined that if Medicare is going to pay for SECULAR treatment (like blood transfusions or life-saving technology), it must be just as willing to pay for ALTERNATIVE treatments like prayer, mediation, and denial of such worldly approaches. In fact, there will now be LESS money to pay for the worldly approaches so that your tax dollars may be spread more equitably among those freely exercising their own approaches to healing and happiness – snake oil, bloodletting, Ayurveda, trepanation, etc.

It’s an extreme example, sure – and I promise you I have absolutely nothing against the JWs or Buddhists. I just don’t want to pay either group out of my tax dollars to provide their own alternatives to modern medical care. Nor do I want to pay evangelicals to educate kids who a mere decade from now will be voting and making world-altering decisions about health care, the role of women in society, civil rights, foreign relations, and whether or not Jesus wants us to beat the sh*t out of the gay kids.

Did I mention that I feel rather strongly about this?

Private Schools Aren’t Meant To Serve Everyone

The lower courts accepted Maine’s use of this program as essentially a substitute for traditional public schools, but Roberts isn’t buying that even a little…

The First Circuit held that the “nonsectarian” requirement was constitutional because the benefit was properly viewed not as tuition assistance payments to be used at approved private schools, but instead as funding for the “rough equivalent of the public school education that Maine may permissibly require to be secular.” …

To start with, the statute does not say anything like that. It says that an SAU without a secondary school of its own “shall pay the tuition . . . at the public school or the approved private school of the parent’s choice at which the student is accepted.” The benefit is tuition at a public or private school, selected by the parent, with no suggestion that the “private school” must somehow provide a “public” education.

He’s not wrong. This was clearly the weak point in the state’s argument to begin with based on the direction the Court has been going with these sorts of issues for the past several decades. I don’t agree with many of those earlier decisions, but given that they’ve become pretty solid precedent, Maine should have seen this coming.

This reading of the statute is confirmed by the program’s operation. The differences between private schools eligible to receive tuition assistance under Maine’s program and a Maine public school are numerous and important. To start with the most obvious, private schools are different by definition because they do not have to accept all students. Public schools generally do. Second, the free public education that Maine insists it is providing through the tuition assistance program is often not free. That “assistance” is available at private schools that charge several times the maximum benefit that Maine is willing to provide.

Ironically, these are two of the primary arguments against “school choice” or “vouchers” as a valid means for improving education for all kids through competition – traditionally one of the primary talking points of the same folks currently giddy over this decision. Private schools always have and always will pick and choose their students, making comparisons to public schools largely meaningless. The “choice” being made is that of each school “choosing” who it will and won’t accept – NOT of parents choosing any school they like. Vouchers make private religious education more affordable for those wealthy enough to pay the difference; poor people are still left choosing from what their coupons will buy.

This decision seems likely to increase that disparity, beginning in Maine.

Moreover, the curriculum taught at participating private schools need not even resemble that taught in the Maine public schools… Participating schools need not hire state-certified teachers… And the schools can be single-sex… In short, it is simply not the case that these schools, to be eligible for state funds, must offer an education that is equivalent—roughly or otherwise—to that available in the Maine public schools.

I don’t believe the Chief Justice intended to echo some of the most common arguments against what counts as “school choice” in many states. He’s simply refuting the idea that these private school options are in any way “just another version of the state providing a public school education.”

Which to my way of thinking, of course, is the whole problem.

But the key manner in which the two educational experiences are required to be “equivalent” is that they must both be secular. Saying that Maine offers a benefit limited to private secular education is just another way of saying that Maine does not extend tuition assistance payments to parents who choose to educate their children at religious schools.

Well, yes. Exactly.

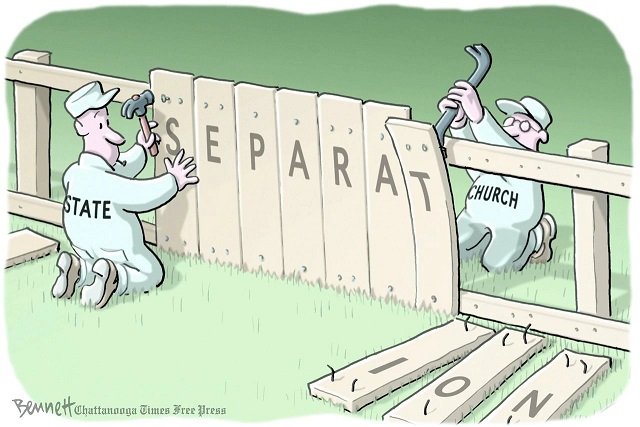

The (Former) Wall Of Separation

This apparent “gotcha” is, in fact, the whole point. States don’t traditionally support religious education because they’re the state. Besides, prior to last week the establishment clause said that was a big no-no.

It’s this next bit, however, that might be my favorite of the entire majority opinion:

Indeed, were we to accept Maine’s argument, our decision in Espinoza would be rendered essentially meaningless. By Maine’s logic, Montana could have obtained the same result that we held violated the First Amendment simply by redefining its tax credit for sponsors of generally available scholarships as limited to “tuition payments for the rough equivalent of a Montana public education” – meaning a secular education. But our holding in Espinoza turned on the substance of free exercise protections, not on the presence or absence of magic words. That holding applies fully whether the prohibited discrimination is in an express provision like {the one in Maine} or in a party’s reconceptualization of the public benefit.

The thing is, if Montana’s voucher program had specified that religious schools were eligible as long as they made some token effort to provide “the rough equivalent of a Montana public education,” we could have avoided all sorts of problems. I might not love the idea of paying religious institutions to perform state functions, but it would at least maintain the principle that public education is intended to provide young people with a fairly consistent body of skills and knowledge and a general understanding of civilized society and their place in it.

Arguments about the fundamental purposes or priorities of public education are varied and endless, but whatever else schools are designed to do, we at least hope they prepare young people to function capably in the world. We hope they’re able to become educated voters, to form meaningful relationships, and to pay their bills and stay out of jail. Some approaches to religion support these goals, many others do not, but public schools make every effort to fulfill these functions without coloring too far outside the lines. It’s impossible to be effective and avoid ANY moral compass in a school setting; if we can’t lay some ground rules about honesty and responsibility and not being horrible to one another, there’s no way we’ll get far teaching them Algebra II. But we try to stay out of anything clearly in the purview of faith.

Religious schools do not return the favor. For many, their faith requires rewriting history, devaluing science, and the labeling of numerous “undesirables.” Free exercise has long meant the state doesn’t prevent those who so choose from indoctrinating their children in this way, whatever the long-term consequences, but for the past half-century at least the rest of us haven’t had to pay for it.

Until now.

The primary impact of Carson v. Makin won’t be limited to rural Maine. In this decision, the Court has stripped away any lingering distinctions between public funding of public good done by religious institutions and public funding of religious instruction, evangelism, or indoctrination. According to this Court, in fact, any distinction between the two is irrelevant. If a state supports a secular effort at promoting the general welfare, it must support religious endeavors which claim even a rough, unverifiable equivalence to those same goals.

It’s hard to imagine this will remain limited even to “school choice” programs. In principle, there’s no reason it should.

As of last week, it is no longer constitutional to distinguish between peer-reviewed history and the Book of Genesis or between medical science and mysticism when it comes to government funding. Public schools will continue to face heavy scrutiny and regulation, while all private alternatives must do to avoid accountability is include religious indoctrination as part of their function. According to the majority of justices, this places them above scrutiny by government bodies at any level thanks to the protections provided by the First Amendment.

I guess we should be glad it’s still doing SOMETHING.

A few days ago, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Carson v. Makin, a case involving state support of religious education in rural Maine. The short version is that states which offer any sort of support for private schooling or alternatives to state-run public schools cannot deny equivalent support to religious institutions claiming a comparable role. These institutions need not follow state curriculums or abstain from indoctrination. They may pick and choose their students on any basis they like and may teach what they like, however they like, and still get paid by the state for each student they choose to accept.

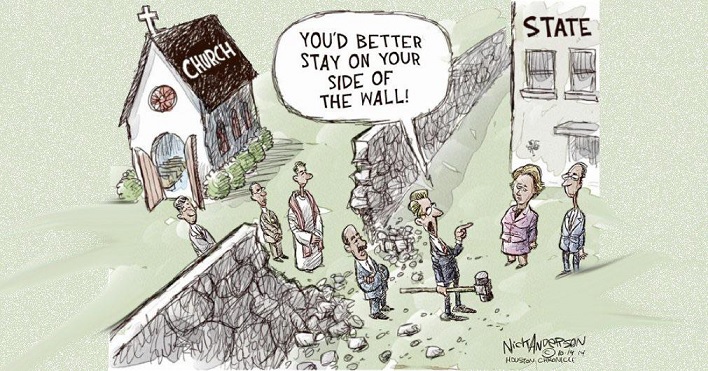

A few days ago, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Carson v. Makin, a case involving state support of religious education in rural Maine. The short version is that states which offer any sort of support for private schooling or alternatives to state-run public schools cannot deny equivalent support to religious institutions claiming a comparable role. These institutions need not follow state curriculums or abstain from indoctrination. They may pick and choose their students on any basis they like and may teach what they like, however they like, and still get paid by the state for each student they choose to accept. Well, any pretense Chief Justice John Roberts has been maintaining about being in any way “moderate” or “reasonable” seems to have been blown to hell this week. The Court’s decision in Carson v. Makin (2022) accelerates the jurisprudential slide away from the proverbial “wall of separation” and elevates the “free exercise” of the minority with the most influence in federal government over the right of anyone else not to pay for it. In the process, the Supreme Court is now openly deriding the suggestion that states have an obligation (or even the right?) to provide a secular public education for kids to begin with.

Well, any pretense Chief Justice John Roberts has been maintaining about being in any way “moderate” or “reasonable” seems to have been blown to hell this week. The Court’s decision in Carson v. Makin (2022) accelerates the jurisprudential slide away from the proverbial “wall of separation” and elevates the “free exercise” of the minority with the most influence in federal government over the right of anyone else not to pay for it. In the process, the Supreme Court is now openly deriding the suggestion that states have an obligation (or even the right?) to provide a secular public education for kids to begin with.