Allusions are one of the trickiest literary devices to teach young people, largely because allusions by their very nature expect the reader to already understand people and events generally considered to be “common knowledge.”

You see the problem.

An effective allusion draws on characters or situations from history, literature, mythology, religion, Shakespeare, or even pop culture (including comics and television) to illuminate a less-familiar character or situation. They add drama, humor, or insight, and potentially offer new layers of context or foreshadowing to the story at hand.

Let’s start with something heavy by way of example. Doctor Martin Luther King, Jr., speaking in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 3rd, 1968 (just 24 hours before his assassination) closed with these words:

It really doesn’t matter what happens now… We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now. Because I’ve been to the mountaintop. And I don’t mind.

Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land!

I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! And I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!

Given that King was a preacher, it’s not exactly a surprise how often he referenced Biblical characters, stories, and values. Just as importantly, his audiences understood these allusions. Whatever the state of their eternal souls, most Americans in the 1960s knew their Bibles. In this case, they knew that after Moses led the Israelites (former slaves who remained marginalized for generations) for four decades, God informed him it was almost time for them to enter the Promised Land – but that Moses himself would not be joining them. By way of consolation, God led Moses to the top of Mt. Pisgah and showed him the land the Israelites would soon inhabit.

King didn’t have to explain the allusion – the audience erupted the moment he said it. The poignance it would carry in after his death wasn’t the issue; it was the idea that all of their struggles had been worthwhile. A new reality was coming, and soon. The implication was that God himself had heard their cries and would be directly involved in making things right. King’s Christ-like acceptance of suffering only reinforced the spiritual dynamics in play.

Notice that my explanation, inadequate as it was, took up way more time and space than what Dr. King said, while still somehow sucking energy and impact out of the story. In less than a dozen words, he brought in emotion, spiritual comfort, and a belief in inevitable victory by layering the right familiar story over his commentary on current events. That’s the power of allusion.

Here’s something a bit more artsy-fartsy, from Leonard Cohen’s “Everybody Knows”:

And everybody knows that the plague is coming – everybody knows that it’s moving fast

Everybody knows that the naked man and woman are just a shining artifact of the past…

Cohen likes to weave in religious imagery for mood even when specific meanings prove elusive (“I heard there was a sacred chord that David played and it pleased the Lord…”), but in this case the subtle allusion to Adam and Eve conjures up the ultimate loss of innocence with tragic consequences. In a song replete with betrayal, failure, and grief, we’re reminded that such experiences aren’t new, they’re foundational in the human experience – which also means we’re not alone.

Ben Folds is even more subtle in “Brick,” a song about a young man taking his girlfriend for a secret abortion and the emotional consequences of the relationship:

Six a.m, day after Christmas – I throw some clothes on in the dark…

Folds uses multiple literary devices throughout this one – imagery, tone, and the recurring “brick” metaphor. It’s possible that “day after Christmas” is simply intended to contrast the narrator’s state of mind with the intended joy of the season. But what is Christmas about, at least traditionally? A birth. A miraculous new baby.

They call her name at 7:30. I pace around the parking lot

And I walk down to buy her flowers and sell some gifts that I got…

They probably weren’t gold, frankincense, and myrrh, so maybe I’m reading too much into this one.

Can’t you see – it’s not me you’re dying for. Now she’s feeling more alone than she ever has before…

Nope. I’m not.

“It’s not me you’re dying for” is not something most of us would say to an aborted fetus, whatever our pain or regret. It does, however, suggest that a baby might be capable of dying “for” someone. You know, like a kid born on Christmas did a few years back.

An already dark situation is made more powerfully tragic by the subtle contrast with the Son of God. A direct comparison would be awkward and absurd, but Fold’s indirect allusion instead adds pathos and depth. The song works without it – it’s just more powerful with it.

Allusion doesn’t have to be heavy. Hanson’s “Juliet” is pretty much ALL allusion, and it’s outright celebratory:

Juliet, you’re my love – I know it’s true that around you I don’t know what to do

Can’t you see that you’re my sun and moon? …

Your window breaks the rising sun – by any other name, you’re still so beautiful

In everything I do, I will love you my whole life – if you’ll be my Juliet …

Juliet, you are a drug and it is quick – and with a kiss I lose my senses

Juliet, you are a fire, I am consumed – tonight I’m dying in your arms …

OK – there’s a tiny little dark undercurrent here (given that in the original, they both actually die in the end), but it’s utilized lightly and ironically. That’s another nice thing about allusions – as long as you honor the truth of the original, you can point it any direction you like. These aren’t scientific truths we’re playing with here; it’s literature, and therefore endlessly flexible and subjective.

Of course, not all allusions have to be profound or complicated. They simply need to bring something to the table – to add meaning, depth, or interest to what’s already being said. Sara Bareilles is arguably better at this than anyone else writing and performing today, as in this excerpt from “Hercules”:

I want to disappear and just start over – so here we are – and I’ll breathe again, ’cause I have sent for a warrior

From on my knees, make me a Hercules – I was meant to be a warrior, please – make me a Hercules

Literature and poetry tend to be more intentional and crafty with their use of allusions, but when learning to spot them and practice explaining them, pop music offers endless examples of the straightforward, “one-and-done” variety.

In “I Say No” from Heathers: The Musical:

You said you’d change, and I believed in you, but you’re still using me to justify the harm you do…

You need help I can’t provide – I’m not Bonnie, you’re not Clyde – it’s not too late, I’m getting straight… I say no!

In “Buddy Holly” by Weezer:

Ooh-wee-hoo, I look just like Buddy Holly – and you’re Mary Tyler Moore

I don’t care what they say about us anyway – I don’t care about that

In “Such A Saint” by Admiral Twin:

She and Joan of Arc were having lunch today down at the Blue Room

She told Joan she’d like to barbecue, then laughed as Joan began to cry

I’ve known evil, mean, bad people kinder than that – if you’re such a saint, reprieve me

The concept can be creatively varied and still be an “allusion,” as in Hindu Rodeo’s “McLife”:

Read my McNews, drink my McJav, eat my Egg McMuffin, kiss my Egg McWife

Go to McWork to get some McClass and buy some McStuff – gotta kick some McA**

I don’t ever think – I don’t even try – I don’t ever live – I like my McLife

I don’t ever dream – I live a McLie – learned to McLive, now I guess I’ll McDie

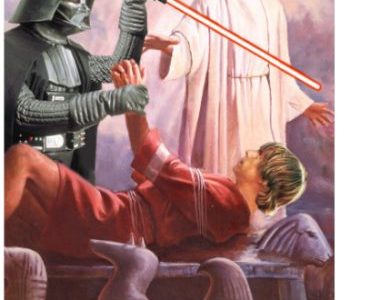

Literature and poetry are less likely to use pop culture references because of how quickly yesterday’s superstars and headlines fade into obscurity. When learning to spot allusions in a classroom setting, however, cartoon characters and comic book superheroes are fairly easy to find. The trick for those of us not traditionally steeped in ELA minutia is to distinguish between actual allusions and simply referencing well-known characters.

When the Spin Doctors sing as Jimmy Olsen assuring Lois Lane that he has a “pocket full of kryptonite,” I’m not sure they’re bringing depth or emotional interest to something new so much as playing with the DC universe for pure entertainment (which is a completely valid artistic expression itself). On the other hand, the Flaming Lips are going for something a bit more complicated in “Waitin’ For A Superman”:

Tell everybody waitin’ for Superman that they should hold on best they can

He hasn’t dropped them – forgotten or anything – it’s just too heavy for Superman to lift

In the end, it’s not always important whether an effective reference to a past character or situation is an “allusion” or just a reference, a “metaphor” or just an analogy. What matters is that it’s effective – that it communicates more completely what the author is trying to express.