“While You Wait” (By Charles Newton Hood) – The Smart Set (June 1900)

SCENE—The cozy breakfast-room in the home of MR. and MRS. RICHARD JAMES VAN CLEEF. Young MR. VAN CLEEF strolls in and is considerably surprised to discover that his charming wife has preceded him, and, what is more, is placidly awaiting his arrival before ordering her own matutinal repast; such a thing being so unusual that MR. VAN CLEEF could scarcely tell the date of its last occurrence; and, furthermore, MRS. VAN CLEEF appears to be mildly interested in his arrival.

SCENE—The cozy breakfast-room in the home of MR. and MRS. RICHARD JAMES VAN CLEEF. Young MR. VAN CLEEF strolls in and is considerably surprised to discover that his charming wife has preceded him, and, what is more, is placidly awaiting his arrival before ordering her own matutinal repast; such a thing being so unusual that MR. VAN CLEEF could scarcely tell the date of its last occurrence; and, furthermore, MRS. VAN CLEEF appears to be mildly interested in his arrival.

MR. VAN CLEEF (in a rather perfunctory way, as he drops into his chair and selects his favorite morning newspaper from the pile by the side of his place)—This is an unexpected pleasure.

Pretty little MRS. VAN CLEEF only smiles in response and rings for breakfast. After the meal is well under way, and MR. VAN CLEEF is beginning to enjoy his coffee—experiencing the odd sensation of having MRS. VAN CLEEF pour it, instead of James, and smiling to discover that she really has forgotten how many lumps of sugar he prefers and how little cream-he is surprised, in the midst of a financial article he is reading in a paper propped up against the fruit dish, to discover that MRS. VAN CLEEF is not partaking of food, but is regarding him with a troubled look. MR. VAN CLEEF glances up inquiringly.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Dick, we’ve done our parts remarkably well, haven’t we?

MR. VAN CLEEF—I don’t exactly understand.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Why, I mean, since we talked it all over three years ago, and decided that we had both made the same mistake—that we were never intended for each other, after all, but that, being married, we’d got to make the best of it. We’ve acted our parts admirably to the world, so that it is doubtful if anyone really suspects that we are not still enjoying an indefinitely extended honeymoon. We have done some remarkably clever acting, for amateurs, and it seems to me that we deserve all of the “good notices” we get in the society columns.

MR. VAN CLEEF does not respond in words, but he looks troubled.

MRS. VAN CLEEF (as if in answer to a protest)—No, Dick, I’m not going to go over the whole story again. Don’t think it! We married because I was old Emprett’s only daughter—tolerably good-looking they used to say—and you were Mr. Richard James Van Cleef, son of the same, and descendant of a long line of Van Cleefs running back a good many generation without ever getting out of alignment; the best catch of the Summer of ’92. The walks and talks, and dances and swims, and books and looks, and moons and spoons, and boating and tennis and all that sort of thing we enjoyed together at Oderkonsett that Summer we thought had developed a sincere and undying affection, and we were really and truly surprised when we discovered, after something over a year of constant companionship, how much we bored each other. I think we were wise, as things looked to us then, to come to the decision we did: to make the best of it; but just tolerably good friends in private, but to keep up the romance so far as other people were concerned. As I say, we’ve done it very credibly. You’ve been very nice to me, and helped me nobly each time we have had to entertain together, and I’ve tried to be everything that could be expected of me except a loving and devoted companion. I’ve never flirted, to speak of, and they do say, Dick, that you have settled down wonderfully since you were married. It has all be done beautifully.

MR. VAN CLEEF (with a puzzled expression)—Well?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Be patient. We decided, on coming to our senses, that we didn’t really love each other at all. You don’t love me now, do you?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Dear! Dear! What is the use of all this? What is the—

MRS. VAN CLEEF—One moment, please. I’ve really got quite deep reasons for it all. (To servant) No, James, we don’t need anything. I shall ring if we do. You see, Dick, I’ve got my plans all laid along a certain line, and I must follow that line or I may get mixed up. You must be very accommodating and answer every question. Now, you don’t really love me at all, do you?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Why, of course, I—

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Now, be honest, speak right out—square-toed, plain, commonsense, hygienic, French-toed without a patent-leather tip, I might say. You know you don’t love me, and why not say so?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Well, then, I don’t.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—That’s right. Not the least little bit in the world?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Why, I suppose—

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Come, come, be honest.

MR. VAN CLEEF (actually grinning a little at the peculiar cross-examination)—Well, then, not the least little bit in the world.

MRS. VAN CLEEF (clapping her hands together ecstatically in front of her face and laughing in a way young MR. VAN CLEEF used to think very charming indeed)—Neither do I you, not the least little bit in the world—not the very least. You’re an awfully nice fellow, and I like you about as well as I do anybody, but I don’t Love you, with a large L, and you don’t Love me, with a large L, and there you are. I wanted to get it all thoroughly understood before I divulged my great plan. Don’t you think that, after all, we’re sort of foolish?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Why, I don’t know; under the circumstances—

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Yes, yes. That’s all right; but we’re young and—nice—and all that, and, someway, do you know, it seems to me that we ought to be privileged to fall in love if we wanted to and—

MR. VAN CLEEF (thinking he sees a light)—Oh, that’s—

MRS. VAN CLEEF (hastily)—Now you’re wrong. You’re wrong. I haven’t fallen in love with anybody, and I don’t suppose that you have, but even if we wanted to, either one of us, we mustn’t, and it doesn’t seem as if we’re being fair to ourselves.

MR. VAN CLEEF—Well?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Well, I have been looking into the matter a little and I think it could all be arranged very nicely and easily, and everything would be lovely. The circular says—

MR. VAN CLEEF—The circular?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Oh, yes, I forgot to tell you. I wrote to some lawyers in Dakota and Oklahoma, who call themselves “Divorce Specialists,” and advertise “Divorces While You Wait;” and, really, the way they put it, all you have to do to get a divorce is just to go out there and spend a few months enjoying the lovely climate and all that, and come back divorced. I think—

MR. VAN CLEEF (excitedly)—Do you mean to say, Mrs. Van Cleef, that you have been writing to those sharks on the subject of divorce?

MRS. VAN CLEEF (placidly)—Why, certainly; but, of course, not in my own name, my dear. Annette attended to that, and I had the letters come to Mrs. J. J. Jones in care of a private post-office on the other side of the city. Annette got the letters for me, but she doesn’t know anything at all about what was in them. I was very particular about that.

MR. VAN CLEEF (with a resigned gasp)—Well, I should hope so. Go on.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Now, in this divorce business, there seems to be a great rivalry between South Dakota and Oklahoma, but the Oklahoma firm’s circular is a good deal the more enticing. Listen. It says (she reads from a circular which she takes from her pocket): “Our newer States, in compiling their laws, have seen fit to show more liberality in the matter of obtaining divorces than may be found among the older states, whose laws on this subject were enacted at a time when ideas were less in accord with the advanced liberal thought of the present.

“As the Mohammedan devotee confidingly turns his eyes toward the tomb of his beloved leader, so has Dakota been regarded as the Mecca of hope to weary companions in matrimony.”

Isn’t that nice? We’ll be the weary companions.

“But,” it says, “Dakota can no longer claim this undivided homage. In the still newer but none the less advanced Commonwealth of Oklahoma she has met a rival, and a fair comparison must show largely to the advantage of the sometime State, and, while the divorce laws are almost identical, the many physical advantages of Oklahoma place her in the lead at once.

“Contemplate, in comparison to the storm-swept plains of Dakota, the picturesqueness of Oklahoma’s ever varying scenery, her fertile fields and blooming prairies, fringed with beautiful groves and ribbed with many a rippling brook. Here nestles the newborn child of the Republic in all her virgin beauty, and here, almost in the centre of the Union, you may enjoy the luxuries of civilization and the rugged beauties of nature while shuffling off the unworthy partner. Here the pleasure seeker and naturalist, while waiting his or her divorce, may revel amid the delights of mountain scenery and explore the caves and cañons so lately the haunts of outlaws. Here the lover of the chase may vent his ardor in pursuit of deer, bear, antelope and mountain lion, while grouse, quail, ducks and geese are plentiful and the streams abound in fish peculiar to Western and Southern waters. The hotels are,” etc., etc.

Isn’t that nice? It says we have to live there only ninety days before we can get a divorce and be as free as the glorious air of Oklahoma. All we have to swear to is that we are uncongenial and incompatible, and you swear that you are a poor, neglected husband, and I’ll swear that I am a poor, neglected wife, and we’ll go out there for a little vacation, and you can hunt and explore and neglect me and be uncongenial and incompatible, and I’ll climb mountains and fish and be incompatible and uncongenial and neglect you, and we’ll have just a lovely time, and there won’t be any scandal, and when we come back we’ll just be good friends and make a joke of it, and you can go your way and I’ll go mine, and—What do you think of it?

MR. VAN CLEEF (looking rather grave)—Why, I have never given the subject thought. It is easily enough arranged, evidently, and if you particularly desire it—

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Now, now; don’t throw it all on me, please, Dick, just because I happened to think the plan all out. Say “we.”

MR. VAN CLEEF—Well, “we,” then. As I say, I haven’t had a chance to think it over, but I suppose, considering the way our lives have been lived for the past few years, it would be the wisest thing to do.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Why, certainly; and I’ve never seen all that Western country at all, and it would be just a lovely trip and outing for us. A sort of farewell tour, you know. When shall we start?

MR. VAN CLEEF (entering more into the spirit of the thing)—Why, if we’re going, we might as well start to-morrow as any time. I don’t suppose they have special excursion rates at regular intervals for parties seeking divorce, have they?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—I don’t suppose so, but it would be an idea for the railroads, wouldn’t it? Sell a round trip ticket for a fare and a third, including a coupon good for one absolute divorce.

MR. VAN CLEEF—Yes, and there could be personally conducted, special car lots of divorce-hunting couples, and we could flirt desperately on the way out and maybe come back married to somebody else.

MRS. VAN CLEEF (gravely)—I don’t believe we’d want to associate much with other people who were looking for divorces, because they might not be as—nice as we are, with their “grounds” taken from the Ten Commandments.

MR. VAN CLEEF—M-m-m. It won’t be necessary to make any special preparations for the trip, will it?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Oh, no, indeed. I don’t suppose we’ll be going out much, and we’ll be roughing it, near to nature’s heart, while we’re waiting. I don’t suppose there’s any special divorce costume necessary.

MR. VAN CLEEF—There really ought to be. Why shouldn’t divorces eventually become a regular social function, the same as swell weddings, to “accord with the advanced liberal thought of the present”?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Yes, indeed. The society columns ought to write them up, the same as they do weddings. Wouldn’t this sound pleasant? (She snatches up a paper and, holding it upside down, pretends to read.)

“A CHARMING DIVORCE

“Mr. and Mrs. Richard James Van Cleef were divorced yesterday morning in the presence of a small company of invited guests, the occasion being one of the most delightful absolute divorce ceremonies seen in Oklahoma this season. Justice Van Brun officiated in his usual impressive manner, his remarks and advice at the close being most felicitous. The couple were divorced standing before a magnificent floral design representing ‘Liberty.’ Mrs. Van Cleef wore a simple yet wonderfully becoming traveling gown of changeable green, and Mr. Van Cleef was attired in the conventional costume for morning divorces. The fair divorcée entered leaning upon the arm of her venerable attorney, but Mr. Van Cleef was entirely unattended. After receiving the congratulations of their many friends,” etc.

Wouldn’t that be nice? But I presume that we can get all we’ll want to take in one trunk.

MR. VAN CLEEF—One trunk? Well, I guess not. We’d fight over who should have it coming back.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Why, that’s so. I never thought of that. We’ll take two small trunks, then.

MR. VAN CLEEF—As long as we are going right through Chicago, we might stop over there—

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Not to get—it—the papers, you don’t mean?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Oh, no; but we haven’t been there since the Fair. Our honeymoon was bright and new then.

MRS. VAN CLEEF (pensively)—Oh, wasn’t it pretty?

MR. VAN CLEEF—What, the moon?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—No, no. The Fair—the grounds, the buildings, and the water. They say nearly every vestige of it is gone now.

MR. VAN CLEEF—Like our honeymoon.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Seems a pity, doesn’t it? Do you remember how we floated around the lagoon in the gondola that night of the illumination? Wasn’t it just too enchanting?

MR. VAN CLEEF—It was, it was. And we thought we were happy.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Why, we were happy!

MR. VAN CLEEF—Were we? It’s so long ago. We’ll go and see the place, anyway.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—I suppose we ought to divide the furnishings and other things we own in common before we go, oughtn’t we?

MR. VAN CLEEF—I suppose it would be less embarrassing. Let me see, what do we own in common?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Why, there’s the big leather chair—

MR. VAN CLEEF—Oh, yes; the chair. May I have that?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Oh, no, Dick. I couldn’t spare that. Don’t you remember, we bought it together and ordered it made especially wide and easy, so that we could both sit in it together before the fire in the library? Don’t you remember?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Oh, yes, I remember. I thought I’d sort of like it as a memento.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Would you? Well, of course you shall have it, but ‘twill break my heart to part with it. And of course you will take your books and I shall take mine. That’s easy.

MR. VAN CLEEF—And the pictures?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Oh, dear me, dear me! We bought almost every one of them together. You choose one first.

MR. VAN CLEEF—I’ll take that marine, “Break, Break, Break.” That ought to be appropriate, under the circumstances.

MRS. VAN CLEEF (with a little gasp)—Why, Dick, that was the very first one we bought. Don’t you remember, we bought it, because I liked it, of the artist himself, and you sulked because I raved over the artist’s hair and eyes, and—

MR. VAN CLEEF—Yes, the confounded little whipper-snapper. I never could abide that sort of men.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Neither can I, but they’re pretty to rave about. We almost quarreled. Do you remember?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Yes. That was the first time.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—And I cried and cried, and you didn’t know what to do, and walked the floor, and by-and-by—

MR. VAN CLEEF—I went and tore your hands away from your eyes—

MRS. VAN CLEEF—And made me let you kiss the tears away.

MR. VAN CLEEF—U-m-m. Now you choose one.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—I’ll take—let me see—“The Elopement.”

MR. VAN CLEEF—But that’s yours, anyway.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Why, so it is! You gave it to me on our first anniversary. How pleased I was! We were awfully happy, weren’t we?

MR. VAN CLEEF—We thought we were.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Why, we were. We ought to be happy now.

MR. VAN CLEEF—We will be, as soon as the knot is untied.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—I wonder if we will?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Why, of course!

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Doesn’t it seem strange?

MR. VAN CLEEF—It do so—it do so.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—What made us get tired of each other, I wonder?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Well, it was like this: The first time I came home drunk from the club you—

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Why, Dick Van Cleef, you never came home drunk to me in your life!

MR. VAN CLEEF—Didn’t I? Well, I have been neglectful, haven’t I? I give it up.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—We just got tired of each other, that’s all. Never mind the dividing. Let’s just plan our trip.

MR. VAN CLEEF—Shall we stop at Niagara Falls?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Oh, let’s! And go to every last place we went to when we stopped there on our wedding trip—Goat Island, and the Three Sisters, and the Whirlpool Rapids, and under the Falls, and the Cave of the Winds, and everywhere.

MR. VAN CLEEF—And we certainly ought to go to Luna Island.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Do you remember the guide telling us about the French couple who couldn’t speak English, and of how he came back from Third Sister Island alone and said that his wife and fallen in, and then afterward confessed that he wanted to get rid of her and had dared her to kneel down and drink out of the rapids, and then, when she tried to do it, he pushed her in?

MR. VAN CLEEF—Yes, I remember. Too bad he didn’t know about Oklahoma!

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Aren’t you a horrid thing!

MR. VAN CLEEF—I am, indeed. And shall we take the Great Lakes trip to Chicago again, too?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Oh, yes, let’s. We did enjoy that so, didn’t we? I do love the water so! The moonlight evenings on deck and—

MR. VAN CLEEF—You probably won’t sit on the deck and go to sleep with your head on my shoulder, as you did on one of the said moonlight nights, will you?

MRS. VAN CLEEF (pensively)—You wouldn’t want me to.

MR. VAN CLEEF—We used to sit there on deck in the evenings for hours without speaking a word. We could do that all right now.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Why, we were just too happy to speak; and besides, we didn’t need to. When you squeezed my hand and I squeezed your hand back again, it meant everything that we could possibly say.

MR. VAN CLEEF—And now, when we sit up there, I can box your ears and you can slap my face, and that will express everything, just the same, without a word being spoken.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Oh, Dick, don’t! Our dear, dead love ought to be sacred, and we did know, because, don’t you remember, we tried it once, and when I squeezed your hand you told me exactly what I was thinking, and when you squeezed my hand back again, I told you. It was a kind of telepathy.

MR. VAN CLEEF—I wonder if it would work now?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Perhaps.

MR. VAN CLEEF (going around behind his wife’s chair and taking one of her hands in his)—Now.

MRS. VAN CLEEF (gently, almost timidly, pressing her husband’s hand)—Now, what am I thinking?

MR. VAN CLEEF (promptly)—You are thinking what a pair of fools we’ve been to make ourselves believe that we didn’t love each other, when we really did, down in our hearts, all of the time, only we were too proud to admit it.

MRS. VAN CLEEF (with a little gasp)—Why, that’s exactly right! Oh, Dick, do you? Do you?

MR. VAN CLEEF (dropping on one knee beside his wife’s chair and choking a little)—Yes, darling.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—And shall we begin all over again and not want any divorce at all—while we wait?

MR. VAN CLEEF (with his arm around his wife’s waist)—Yes, dearest. But why not take the trip, just the same?

MRS. VAN CLEEF—Oh, yes; let’s take one every year at just this time—

MR. VAN CLEEF—And call them our regular annual farewell tours. We’ll start to-morrow.

MRS. VAN CLEEF—With one trunk.

Helen Churchill Candee was born in 1858 as Helen Churchill (her mother’s maiden name) Hungerford of New York. Her father was a successful merchant, and Helen grew up in relative comfort both there and in Connecticut where the family moved shortly thereafter. More important than the physical provisions prosperity allowed, she was exposed to ideas and stories, music and art, history and culture, in ways unlikely to have been possible had she lived a generation before, or anywhere else.

Helen Churchill Candee was born in 1858 as Helen Churchill (her mother’s maiden name) Hungerford of New York. Her father was a successful merchant, and Helen grew up in relative comfort both there and in Connecticut where the family moved shortly thereafter. More important than the physical provisions prosperity allowed, she was exposed to ideas and stories, music and art, history and culture, in ways unlikely to have been possible had she lived a generation before, or anywhere else.  Oklahoma Territory had them all beat, however. Ninety days – that’s how long you needed to establish residency. Three short months and you were eligible to file. If your soon-to-be ex didn’t show, the court appointed someone to speak on his or her behalf, whether they knew their “client” or not. Generally, things were wrapped up in time to grab some lunch before getting back to watching lazy hawks circle in the sky and whatnot.

Oklahoma Territory had them all beat, however. Ninety days – that’s how long you needed to establish residency. Three short months and you were eligible to file. If your soon-to-be ex didn’t show, the court appointed someone to speak on his or her behalf, whether they knew their “client” or not. Generally, things were wrapped up in time to grab some lunch before getting back to watching lazy hawks circle in the sky and whatnot. Between 1896 and 1901, Candee wrote six pieces for five different periodicals about Oklahoma Territory and life therein. They’re strong enough to consider individually, but what they demonstrate consistently is her knack for capturing things like crop production reports and detached observations on cultural evolution while always circling back to the human experience that makes all the rest of it matter.

Between 1896 and 1901, Candee wrote six pieces for five different periodicals about Oklahoma Territory and life therein. They’re strong enough to consider individually, but what they demonstrate consistently is her knack for capturing things like crop production reports and detached observations on cultural evolution while always circling back to the human experience that makes all the rest of it matter.

I’ve been trying to follow up on a

I’ve been trying to follow up on a  A “foundling” was an unattached child – an orphan, or possibly a kidnapped baby or a child sold off for whatever reason. Apparently you could pick up a kid or three for next-to-nothing in those years. As to the “Eva Hamilton” reference, Hamilton was part of a

A “foundling” was an unattached child – an orphan, or possibly a kidnapped baby or a child sold off for whatever reason. Apparently you could pick up a kid or three for next-to-nothing in those years. As to the “Eva Hamilton” reference, Hamilton was part of a  My first inclination was to question the term “blanket” divorce, given the slang and mindset towards Amerindians at the time. Pretty sure I was reading too much into the term, however.

My first inclination was to question the term “blanket” divorce, given the slang and mindset towards Amerindians at the time. Pretty sure I was reading too much into the term, however. OK, I have to admit this caught my attention.

OK, I have to admit this caught my attention. I’ve been looking into the “divorce industry” in Oklahoma Territory (1889 – 1907). I’ve

I’ve been looking into the “divorce industry” in Oklahoma Territory (1889 – 1907). I’ve  There’s another reference which presumably meant something to contemporaneous readers – “the female Parkhurst.” From context, we can reasonably infer he must have been some sort of reformer, perhaps a—

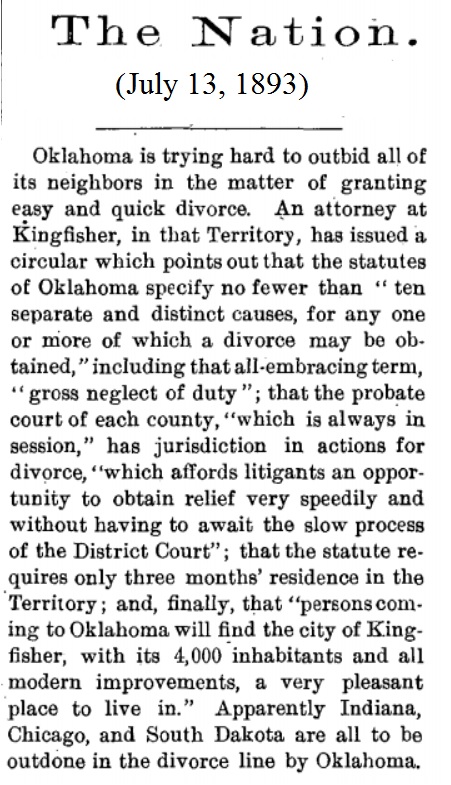

There’s another reference which presumably meant something to contemporaneous readers – “the female Parkhurst.” From context, we can reasonably infer he must have been some sort of reformer, perhaps a— Oklahoma is trying hard to outbid all of its neighbors in the matter of granting easy and quick divorce. An attorney at Kingfisher, in that Territory, has issued a circular which points out that the statutes of Oklahoma specify no fewer than “ten separate and distinct causes, for any one or more of which a divorce may be obtained,” including that all-embracing term, “gross neglect of duty”…

Oklahoma is trying hard to outbid all of its neighbors in the matter of granting easy and quick divorce. An attorney at Kingfisher, in that Territory, has issued a circular which points out that the statutes of Oklahoma specify no fewer than “ten separate and distinct causes, for any one or more of which a divorce may be obtained,” including that all-embracing term, “gross neglect of duty”…