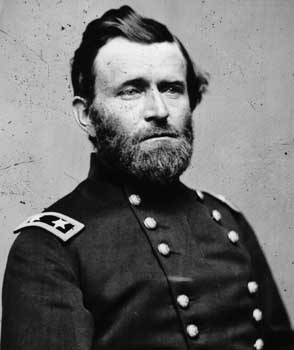

Grant was perhaps the single most bearded example of nothing working quite the way it should have during the American Civil War. He’d have never ended up a war hero, let alone future President, in a more ordered universe. I’m not sure he’d have existed at all.

Grant was perhaps the single most bearded example of nothing working quite the way it should have during the American Civil War. He’d have never ended up a war hero, let alone future President, in a more ordered universe. I’m not sure he’d have existed at all.

He did, however – and oh the shenanigans.

Born “Hiram Ulysses Grant,” he became “Ulysses S. Grant” through a paperwork error when admitted to West Point at age 17 (never let it be said the federal government places a priority on accuracy). This would later come in handy as he entered national consciousness for his accomplishments on the battlefield, as the new moniker lent itself to such natural wordplay: “U.S.” Grant, “Uncle Sam” Grant, and eventually “Unconditional Surrender” Grant… but I’m getting ahead of myself.

He didn’t initially care much for the militant life, and his grades reflected such. Still, he did well in the subjects he liked. He was strong in math, excelled in horsemanship, and he… um… painted. Not, like, battle scenes or modern art or something – “pretty” stuff. It was the ‘Romantic Era’, after all.

A reasonable universe would never send this boy to war. Instead, he’d be running the Artistic Equestrian Ranch or some other utopian-ish community where people get in touch with their inner alcoholic and work the steps through painting and pony-play.

Oh – because that was the other thing. Grant was often accused of being quite the drinker.

To be thought of as having a ‘drinking problem’ by the standards of the day required an insane amount of imbibery. Americans were serious drinkers by ANY definition. Imagine calling out a teenager today for having a ‘social media and reality TV’ problem compared to his or her peers. My god – how bad would it have to be…?

Then again, maybe it wasn’t true. Grant didn’t like most people and didn’t make much effort to be popular. This probably didn’t help when it came to his reputation or his business dealings, both during and after the Mexican-American War. He served quite effectively, but resigned while stationed waaaayyyyyyyy over in California – most likely under pressure over the drinking thing. And, being himself, he lacked the funds to get back to St. Louis.

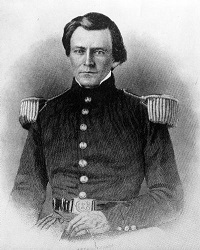

Fortunately, a good friend serving with him, one Simon Bolivar Buckner, proffered a personal loan so that Grant could return to his hearth and kin.

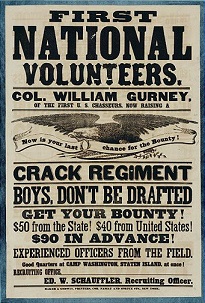

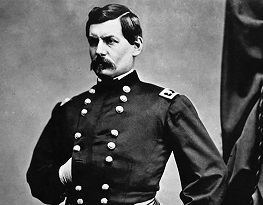

After several years of failed businesses and rocky times, opportunity struck when the Civil War erupted. He helped recruit and train volunteers in Illinois, but what he really wanted was a position in the “real” army. McClellan turned him down due to his reputation for drinking, which will prove ironic a few years later when Lincoln suggests someone find out WHAT Grant was drinking – and send it to the rest of his generals so they’d fight like he did.

After several years of failed businesses and rocky times, opportunity struck when the Civil War erupted. He helped recruit and train volunteers in Illinois, but what he really wanted was a position in the “real” army. McClellan turned him down due to his reputation for drinking, which will prove ironic a few years later when Lincoln suggests someone find out WHAT Grant was drinking – and send it to the rest of his generals so they’d fight like he did.

Lincoln was a bit of a card that way.

Eventually Grant ends up in the Western Theater of the war (which at the time meant the vicinity of the Mississippi River). He was beginning to be noticed, particularly for his willingness to fight. Others (most notably McClellan in the East) would equivocate, fight only when unavoidable, and withdraw too easily – after wins OR losses. It could be frustrating for those who hoped the war would maybe, like, END someday, or that maybe we’d even WIN at some point.

Grant, though, was a bulldog – he didn’t seek war, but if we’re gonna war, let’s WAR.

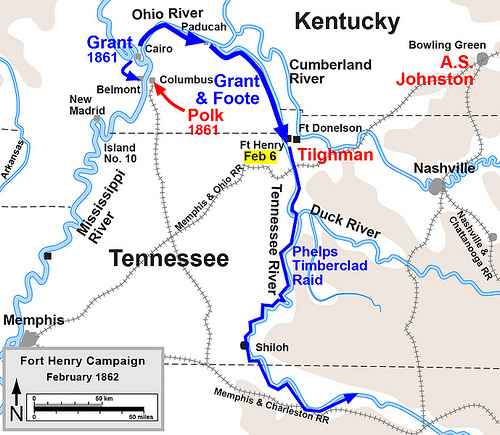

He ended up leading a little campaign to take Ft. Henry along the Tennessee River, which connected to the Mississippi and ran near or through about 43 different states in play during the war. It became a fun little experiment in geography, strategy, and the pre-cell phone zaniness of coordinating land forces and ‘ironclads’ – experimental watercraft made of wood but clad in, well – iron.

He ended up leading a little campaign to take Ft. Henry along the Tennessee River, which connected to the Mississippi and ran near or through about 43 different states in play during the war. It became a fun little experiment in geography, strategy, and the pre-cell phone zaniness of coordinating land forces and ‘ironclads’ – experimental watercraft made of wood but clad in, well – iron.

The thing with boats was, you could make them float, or you could make them strong – but doing both at the same time was tricky. It must have been comical watching them in action, trying to maneuver, and fire at stuff from the water – if it weren’t for all the sinking and loudness and dying, I mean.

In any case, through an impressive combination of strategy and grit, he forced the fort’s surrender.

As Henry falls, Grant does something unusual for a Union General at the time but which it never would have occurred to him NOT to do – he rushes 12 miles east with his army and takes Ft. Donelson as well.

Of course. Because… war.

It’s at Ft. Donelson that U.S. Grant first makes the history books. After various military maneuvering of the sort some people seem to enjoy reading about in great detail, Grant had the Confederates in a world of hurt.

It’s at Ft. Donelson that U.S. Grant first makes the history books. After various military maneuvering of the sort some people seem to enjoy reading about in great detail, Grant had the Confederates in a world of hurt.

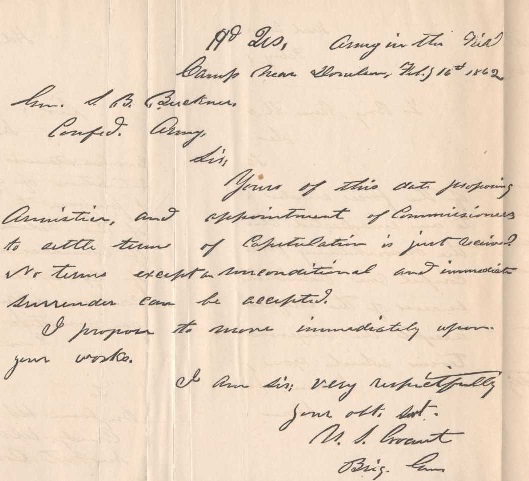

Early morning, February 16th, the leader of Secesh forces there sent a very civil note to Grant requesting a meeting to discuss terms of surrender. War was SO polite back then, with social graces and compliments and people getting to keep their fancy guns and such. This particular leader was confident Grant would be gracious, both as a matter of course, and because the last time they’d been face to face, he’d loaned him bus fare back to St. Louis.

The guy fighting for the wrong side at Ft. Donelson was Simon Bolivar Buckner.

Grant’s response has become legendary:

Sir: Yours of this date proposing Armistice, and appointment of Commissioners, to settle terms of Capitulation is just received. No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted.

I propose to move immediately upon your works.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

U.S. GRANT,

Brigadier-General, Commanding.

It wasn’t personal – they were in rebellion against the very nation Grant was sworn to serve. Buckner had little choice but to comply.

SIR:—The distribution of the forces under my command, incident to an unexpected change of commanders, and the overwhelming force under your command, compel me, notwithstanding the brilliant success of the Confederate arms yesterday, to accept the ungenerous and unchivalrous terms which you propose.

I am, sir, your very obedient servant,

S. B. BUCKNER,

Brigadier. General, C. S. Army.

Did you notice he left out the ‘respectfully’ part of the froo-froo sig? And you gotta love Buckner’s defense of his Confederate peeps even as he becomes the first Confederate General to surrender anything important during this war – “unless my superiors show up unexpectedly, and keeping in mind that we beat you in EVERY STAT EXCEPT SCORING, I guess I have to accept your terms, despite you being a bit of a dillweed about it.”

Once that bit of unpleasantness was concluded, Grant was thoroughly gracious to Buckner and his staff. He offered him funds to help tie him over while he was a prisoner of war, and suggesting Buckner could grab a few personal items if he wished before they confiscated all of their equipment and such.

Buckner declined.

Northern newspapers reported both the military success and the exchange of notes with unrestrained glee. Hiram Ulysses was thereafter “Unconditional Surrender” Grant and the North finally had a win, and a hero with a catchy nickname to go with it. Had West Point gotten his name right to begin with, they’d have had only the initials ‘H.U.G’ to work with, and that would have just been awkward.

“I propose to move immediately upon your works” became a catchphrase throughout the North for almost any situation. Those of you who endured the decades of “Where’s the Beef?” or “Whatchu talking’ bout, Willis?” know how these things can go. Then again, this one grew organically – not as a result of marketing or even intent – so perhaps bringing up Different Strokes is a bit too harsh.

“I propose to move immediately upon your works” became a catchphrase throughout the North for almost any situation. Those of you who endured the decades of “Where’s the Beef?” or “Whatchu talking’ bout, Willis?” know how these things can go. Then again, this one grew organically – not as a result of marketing or even intent – so perhaps bringing up Different Strokes is a bit too harsh.

Besides, because people back home were by definition not AT war, it was most often used in other contexts – the best of which were completely inappropriate.

“Oh, Robert, you do know how to flatter and fluster a girl.” *fan* *fan* *fan* *fan* “It’s growing late, Robert… I should be getting back before they realize I’m not- Robert! Whatever are you-?”

“Louise, I propose to move immediately upon your works.”

I don’t actually know how successful this line proved as a general rule, but it amuses me to no end. It could be used much more harshly or far more humorously, but as a “just the right amount of naughty” come-on, it’s golden.

There’s probably a pretty strong case to be made that equating of military violence with sexual conquest has a negative side to it as well, but that’s for another day and another blog. As a straight white male whose sense of humor is stuck in middle school, it’s right up there with a good Canterbury fart joke or Ben Franklin arguing the merits of seducing older women.

Clearly the best, undiscovered sobriquet for our favorite general has to be “Usurpingly Sexy” Grant. He can move on my works any time.

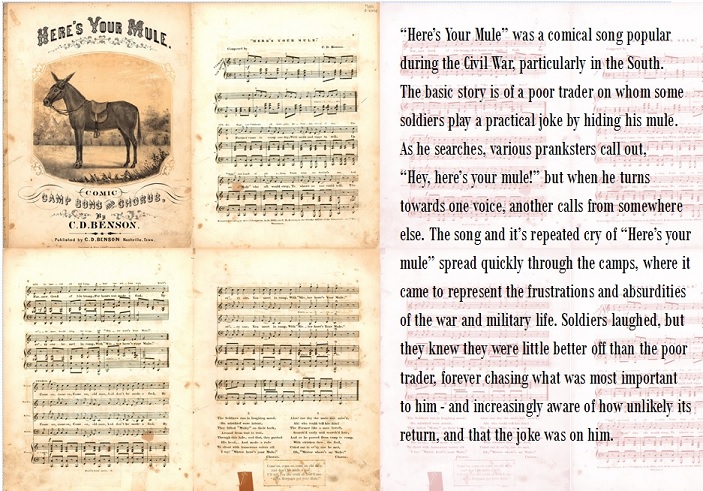

RELATED POST: “Here’s Your Mule,” Part One – North vs. South

RELATED POST: “Here’s Your Mule,” Part Two – Slavery & Sinners

RELATED POST: “Here’s Your Mule,” Part Three – That Sure Was Sumter

RELATED POST: “Here’s Your Mule,” Part Four – On To Richmond!

RELATED POST: “Here’s Your Mule,” Part Five – Bull Run Goes South

RELATED POST: “Here’s Your Mule,” Part Six – Soiled Armor

Your standard American History textbook will tell you that after First Bull Run, the Union realized the War was going to be a bit trickier than they’d thought, and began preparing more substantially. The South, on the other hand, felt validated in their assessment of the Yanks and suffered from overconfidence.

Your standard American History textbook will tell you that after First Bull Run, the Union realized the War was going to be a bit trickier than they’d thought, and began preparing more substantially. The South, on the other hand, felt validated in their assessment of the Yanks and suffered from overconfidence.  The vanity and honor culture of the South was pretty much unbearable long before First Bull Run, but their routing of the North after such build-up and so many supposed disadvantages reinforced the conviction of many Secesh that they simply could not, would not, should not lose – ever ever ever ever.

The vanity and honor culture of the South was pretty much unbearable long before First Bull Run, but their routing of the North after such build-up and so many supposed disadvantages reinforced the conviction of many Secesh that they simply could not, would not, should not lose – ever ever ever ever.

Here’s the problem with that kind of enemy: they don’t give up. I mean, I’m a big fan of all that ‘hold on tight to your dreams’ stuff, but there’s a time to make like Elsa and let it go.

Here’s the problem with that kind of enemy: they don’t give up. I mean, I’m a big fan of all that ‘hold on tight to your dreams’ stuff, but there’s a time to make like Elsa and let it go. Germany took a pretty severe beating before Hitler’s suicide opened the door to surrender, leaving Japan alone in the fight – but they couldn’t let themselves accept the inevitable. WE DROPPED AN ATOMIC BOMB ON THEM, and they were still, like “I dunno – seems to me we can still make this work.”

Germany took a pretty severe beating before Hitler’s suicide opened the door to surrender, leaving Japan alone in the fight – but they couldn’t let themselves accept the inevitable. WE DROPPED AN ATOMIC BOMB ON THEM, and they were still, like “I dunno – seems to me we can still make this work.” If Bull Run left the South feeling confirmed in their invulnerability, it left the North soiling their armor at rabbits. Yes, the President and co. dug in for a real war, but the psychological impact of blowing a ‘sure thing’ – so much so that they skulked back to Washington in terror and shame – didn’t fade quickly. Add to this the grand delusions of General George B. McClellan, who led Union troops through much of the first part of the war – and we have a problem.

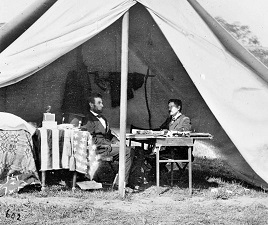

If Bull Run left the South feeling confirmed in their invulnerability, it left the North soiling their armor at rabbits. Yes, the President and co. dug in for a real war, but the psychological impact of blowing a ‘sure thing’ – so much so that they skulked back to Washington in terror and shame – didn’t fade quickly. Add to this the grand delusions of General George B. McClellan, who led Union troops through much of the first part of the war – and we have a problem.  You’d think this would mean less bloodshed, but in reality it protracted the conflict unnecessarily for months – maybe years. It drove Lincoln crazy, despite his calm veneer – at one point he wrote to McClellan asking if perhaps he could borrow the army for a time, seeing as how he wasn’t using it for anything.

You’d think this would mean less bloodshed, but in reality it protracted the conflict unnecessarily for months – maybe years. It drove Lincoln crazy, despite his calm veneer – at one point he wrote to McClellan asking if perhaps he could borrow the army for a time, seeing as how he wasn’t using it for anything.

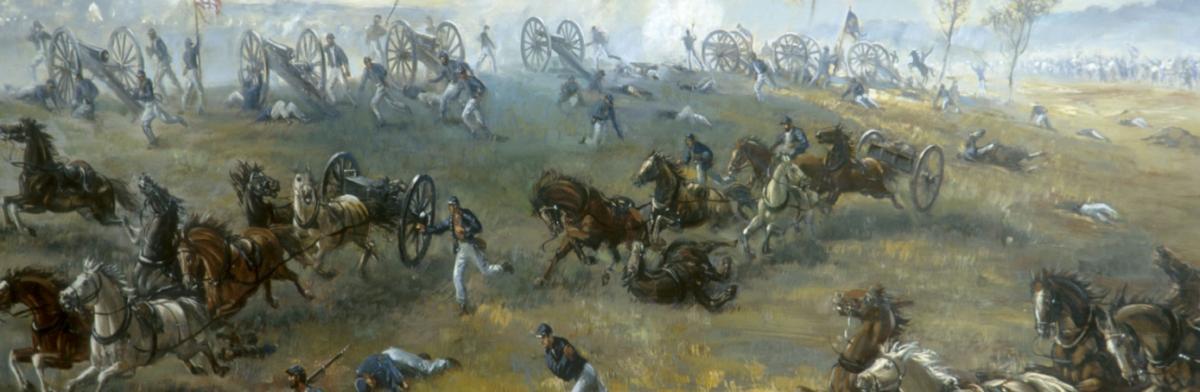

Through the smoke and haze of battle, the boys who would later be in blue could tell fresh troops were falling into place across the way. Those looking behind for their own reinforcements were… disappointed.

Through the smoke and haze of battle, the boys who would later be in blue could tell fresh troops were falling into place across the way. Those looking behind for their own reinforcements were… disappointed.  OK, he was already weird before the battle. A brilliant strategist, Jackson was nonetheless an unlikely leader of men. He was socially awkward, and his classes at Virginia Military Institute were notorious for their tedium.

OK, he was already weird before the battle. A brilliant strategist, Jackson was nonetheless an unlikely leader of men. He was socially awkward, and his classes at Virginia Military Institute were notorious for their tedium. It was THIS figure who confronted the men who’d begun to fall back in the face of superior firepower. Jackson didn’t yell, so his voice would have been raised only in order to be heard above the din. He told them to form a line and hold it.

It was THIS figure who confronted the men who’d begun to fall back in the face of superior firepower. Jackson didn’t yell, so his voice would have been raised only in order to be heard above the din. He told them to form a line and hold it. General Bee, who was not particularly weird OR inspiring, saw this from across the way and recognized its power. Knowing he couldn’t pull it off personally, he instead pointed it out to his men: “Look! There’s Jackson, standing like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!”

General Bee, who was not particularly weird OR inspiring, saw this from across the way and recognized its power. Knowing he couldn’t pull it off personally, he instead pointed it out to his men: “Look! There’s Jackson, standing like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!”  First Bull Run was the first time Union troops would experience one of the more bone-chilling elements of the Civil War. This was possibly Jackson’s doing as well. (Hey, once you’ve got a cool nickname, anything is possible.)

First Bull Run was the first time Union troops would experience one of the more bone-chilling elements of the Civil War. This was possibly Jackson’s doing as well. (Hey, once you’ve got a cool nickname, anything is possible.)

And yet, things remained relatively calm. Disorderly, to be sure – frustrating, and volatile. But there was no panic – at first.

And yet, things remained relatively calm. Disorderly, to be sure – frustrating, and volatile. But there was no panic – at first.  Your standard American History textbook will tell you the Union realized the War was going to be a bit trickier than they’d thought, and begin preparing more substantially. The South, on the other hand, felt validated in their assessment of the Yanks and suffered from overconfidence.

Your standard American History textbook will tell you the Union realized the War was going to be a bit trickier than they’d thought, and begin preparing more substantially. The South, on the other hand, felt validated in their assessment of the Yanks and suffered from overconfidence.

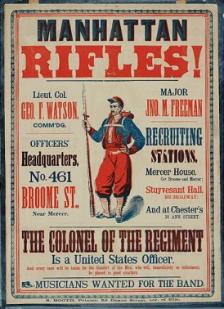

After Sumter, the Union called for soldiers from the loyal states, some of whom actually sent them. Generals were often elected by their men or appointed for their political connections, so knowing what you were doing wasn’t really top priority at this stage. Men signed up eagerly for the good times to come – war was a mostly theoretical adventure, and defeating the silly South would be good times.

After Sumter, the Union called for soldiers from the loyal states, some of whom actually sent them. Generals were often elected by their men or appointed for their political connections, so knowing what you were doing wasn’t really top priority at this stage. Men signed up eagerly for the good times to come – war was a mostly theoretical adventure, and defeating the silly South would be good times.  President Lincoln appointed Irvin McDowell to make this happen, but McDowell was skeptical about the supposed ease of such a mission. He’d done real war before, and was concerned about trying to send men into battle based on the harassment of impatient politicians and newspapers. He was famously reassured by President Lincoln, “You are green, it is true, but they are green also; you are all green alike.”

President Lincoln appointed Irvin McDowell to make this happen, but McDowell was skeptical about the supposed ease of such a mission. He’d done real war before, and was concerned about trying to send men into battle based on the harassment of impatient politicians and newspapers. He was famously reassured by President Lincoln, “You are green, it is true, but they are green also; you are all green alike.”

Unfortunately P.G.T. Beauregard, our friend from the attack on Ft. Sumter, was waiting for him just outside of Richmond. He had a plan as well, once the Yankee oppressors arrived – fake to the right, attack hard on the left, flank the enemy. Once between the army and the capital, they’d have no choice but to surrender. War over – here comes the honor and the glory (and let’s use some discretion regarding the ladies).

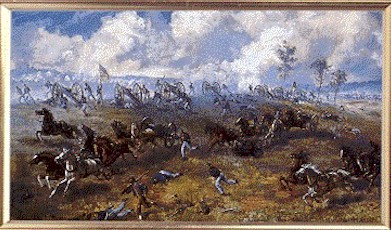

Unfortunately P.G.T. Beauregard, our friend from the attack on Ft. Sumter, was waiting for him just outside of Richmond. He had a plan as well, once the Yankee oppressors arrived – fake to the right, attack hard on the left, flank the enemy. Once between the army and the capital, they’d have no choice but to surrender. War over – here comes the honor and the glory (and let’s use some discretion regarding the ladies).  People were getting SHOT! IN THE BODY! Cannonballs were tearing off limbs, and bullets were splattering the brains of friends. Many bowels and bladders were emptied in those opening hours, and shame quickly gave way to survival instinct for some as this glorious adventure turned out to suck majorly. This was NOT GLORIOUS AND WHAT THE HELL THEY’RE TRYING TO KILL US ALL!

People were getting SHOT! IN THE BODY! Cannonballs were tearing off limbs, and bullets were splattering the brains of friends. Many bowels and bladders were emptied in those opening hours, and shame quickly gave way to survival instinct for some as this glorious adventure turned out to suck majorly. This was NOT GLORIOUS AND WHAT THE HELL THEY’RE TRYING TO KILL US ALL!  Mrs. Chesnut has been recording for posterity the events surrounding the so-called “Battle of Fort Sumter.” Except she’s mostly not.

Mrs. Chesnut has been recording for posterity the events surrounding the so-called “Battle of Fort Sumter.” Except she’s mostly not.

That Chesnut always returns to the sincere – the experience – anchors her prose in a way mere observation or fiction could not. Her ability to grab descriptive slices of people and events and weave them in so transparently makes this something more alive than most find mere history to be.

That Chesnut always returns to the sincere – the experience – anchors her prose in a way mere observation or fiction could not. Her ability to grab descriptive slices of people and events and weave them in so transparently makes this something more alive than most find mere history to be.

“A satisfying faith” – once again, understated layers of meaning. Chesnut doesn’t directly comment, she portrays – with precision. I think she’s aware of us, all these years later, reading her through this… ‘documentation’ of events. Do you feel her Mona Lisa smirk on us?

“A satisfying faith” – once again, understated layers of meaning. Chesnut doesn’t directly comment, she portrays – with precision. I think she’s aware of us, all these years later, reading her through this… ‘documentation’ of events. Do you feel her Mona Lisa smirk on us?  The standard American History book will tell you the South was overconfident after First Bull Run, etc. I’d argue Colonel Manning and his ilk were way ahead of the crowd on this one.

The standard American History book will tell you the South was overconfident after First Bull Run, etc. I’d argue Colonel Manning and his ilk were way ahead of the crowd on this one.