Land was a big deal when our little experiment in democracy began. Why?

Let’s ask the Founding Fathers. They seemed bright.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…

(Declaration of Independence, 1776)

Consent of the governed? As in, the people being ruled make the rules, and all that? Huh – big responsibility. Harder than it sounds.

Given the number of reality shows based on the challenges of a dozen or so people living together in a free house with unlimited alcohol and no jobs, running an entire country based on the collective will of the masses seems… problematic. “Come at me, IDAHO!”

And the rallying cry had been “No taxation without representation!” The phrase has survived, but over the years we’ve lost sight of something rather obvious in these words, and inherent to our founding ideology: If paying taxes means you deserve to have a voice in your government, then it’s not unreasonable to suggest that having a voice in your government is contingent on your willingness and ability to pay taxes.

In other words, you have to own something valuable enough to be taxed. Like, say… land.

So we have two issues in play as the Founders wrestle with outlining this new government – the connection between paying into the system and thus earning a voice in the running of that system, and the practical challenges of who exactly “consents” to that government on behalf of the whole. Little wonder our progenitors might try to reconcile them in concert – hopefully without overtly dialing back those fancy new ideals they’d been proclaiming to justify the entire project.

They weren’t starting from scratch. There were some longstanding assumptions about land ownership – or the lack thereof – with which they could begin.

If it were probable that every man would give his vote freely, and without influence of any kind, then, upon the true theory and genuine principles of liberty, every member of the community, however poor, should have a vote…

You gotta pay close attention when any argument begins with “in theory…”

But since that can hardly be expected, in persons of indigent fortunes, or such as are under the immediate dominion of others, all popular states have been obliged to establish certain qualifications, whereby, some who are suspected to have no will of their own, are excluded from voting; in order to set other individuals, whose wills may be supposed independent, more thoroughly upon a level with each other.”

(Alexander Hamilton, Quoting Blackstone’s Commentaries on The Laws of England, 1775)

So, in order to assure that everyone’s political voice is more or less equal, we’re going to have to deny a political voice to some – to those without the ability to provide for themselves. Otherwise, the entire representative system may be undermined through the ability of the wealthy to manipulate the indigent.

Ironic, huh?

Then again, Hamilton was kinda Machiavellian about such things. Maybe someone less… cynical?

Viewing the subject in its merits alone…

That sounds a whole lot like “in theory” again…

…the freeholders of the country would be the safest depositories of republican liberty. In future times the great majority of the people will not only be without landed, but any other sort of property. These will either combine under the influence of their common situation, in which case the rights of property and the public liberty will not be secure in their hands; or, which is more probable, they will become the tools of opulence and ambition, in which case there will be equal danger on another side.

(James Madison, Speech in the Constitutional Convention, August 1787)

No help here from the ‘Father of the Constitution’. Apparently handing power over to men without land leads to either a tyranny of the masses (mob rule) or a system in which the ignorant and easily agitated are led about by the manipulations of the wealthy and power-hungry.

My god, we wouldn’t want that. Can you imagine?

It appears that while our new nation was taking the concept of self-rule well beyond anything previously attempted, there were still substantial concerns over appropriate limits. This isn’t a dilemma unique to starting new nations. It’s one thing to talk about student-directed learning, for example, but quite another to hand them the chalk and the wifi password and tell them you’ll check back in May.

Get too idealistic, and the system devolves into chaos. Maintain too much structure – aka, limitations – and you quickly become just like whatever system you were trying to get away from. It’s like trying to balance Jello on your nose while you learn to unicycle.

Hey – you know who we didn’t ask? Jefferson! I mean, you can find quotes from Jefferson to prove just about anything, right?

You have lived longer than I have and perhaps may have formed a different judgment on better grounds; but my observations do not enable me to say I think integrity the characteristic of wealth. In general I believe the decisions of the people, in a body, will be more honest & more disinterested than those of wealthy men: & I can never doubt an attachment to his country in any man who has his family & peculium in it…

(Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Edmund Pendleton Philadelphia, Aug. 26, 1776)

I had to look up ‘peculium’. It means ‘stuff’ – including family, income, etc. Not quite the same as land, but still property – still evidence of competence via one’s successful estate. In other words, no help from T.J.

Jefferson here confesses to a sort of paradox – he doesn’t believe for a moment that wealth indicates personal integrity or even political wisdom. At the same time, he finds it easier to trust the input of someone who’s invested in the success of the nation of which they’re a part.

It’s the difference between shopping at Bobo’s Grocery Extravaganza and working there, or between working at Bobo’s and investing your life savings in Bobo stock. If I’m a shopper and Bobo’s fails, it’s merely inconvenient. If I work there and it fails, it’s a problem.

But if my kids’ college savings and my retirement are all tied up in Bobo’s, I’m going to go above and beyond to do a great job every time I’m there. I may clean up even when that’s not part of my job, or study up on products I’m not actually required to know about. I’ll certainly be ultra-friendly to every customer who walks in the door. Heck, I may come in on my day off just to kinda help out.

Because I’m invested.

Land ownership suggests one is not only capable, but invested in the nation’s success. If I’m a landowner, I care very much about the next election, the local statutes, the state questions. Crazy Harold who lives under the bridge talking to his urine may be a nice guy, but he’s not overly concerned with researching the finer points of foreign policy.

Well, unless his pee tells him to.

So it seems that whatever else they argued about, our Founding Fathers were largely in agreement about one thing. Landowners were reliable, and self-sufficient. Their voice was their own. Those without? Not so much.

Keep in mind this was a new country – a baby nation. The Declaration was as much a birth certificate as a break-up letter, and our forebears were trying something entirely new. They were idealists, sure – but they were also educated, and realists, and had some idea of the ways in which people tend to behave.

If this ‘self-government’ thing didn’t work, America would fail. If America failed, then democracy had failed. And if democracy failed here, it effectively failed everywhere – in many cases it would never even begin.

The Dark Ages would return – tyranny and ignorance. Monsters once again rule the earth. It would be what we in the social sciences call “bad.”

It was John Adams (of all people) who best explained how the young nation could be both a land of opportunity and pragmatically defend itself against fools and freeloaders.

It is certain in Theory, that the only moral Foundation of Government is the Consent of the People.

There’s that “in theory” again…

But to what an Extent Shall We carry this Principle? Shall We Say, that every Individual of the Community, old and young, male and female, as well as rich and poor, must consent, expressly to every Act of Legislation? No, you will Say. This is impossible…

Adams probably talked too much, but I do love how he steps his audience through his reasoning. It’s very Socrates, very Holmes, very Bill Nye the Government Guy. Franklin may have been the poster child of the Enlightenment in the New World, but Adams was its lesson-planner and incessant blogger.

But why exclude Women? You will Say, because their Delicacy renders them unfit for Practice and Experience, in the great Business of Life, and the hardy Enterprizes of War, as well as the arduous Cares of State. Besides, their attention is So much engaged with the necessary Nurture of their Children, that Nature has made them fittest for domestic Cares. And Children have not Judgment or Will of their own…

How did Abigail not kill him regularly?

I know a number of impressive women both professionally and personally. They are varied and wonderful creatures, but very few qualify for the epithet ‘delicate’. Clearly John was not in the room during childbirth.

But will not these Reasons apply to others? Is it not equally true, that Men in general in every Society, who are wholly destitute of Property, are also too little acquainted with public Affairs to form a Right Judgment, and too dependent upon other Men to have a Will of their own? … Such is the Frailty of the human Heart, that very few Men, who have no Property, have any Judgment of their own…

There it is – the same basic argument which was made time and again by our Framers. You gotta pass the 8th grade reading test to take Driver’s Ed, you gotta keep a ‘C’ average or better to play football, and you gotta have your own land to vote. It’s nothing personal. It’s simply an imperfect indicator of minimal competence.

Doctors gotta have degrees to doctor on you. Accountants have to be certified to do spreadsheets on your behalf. Barbers have to have special certificates confirming their competence to snip your hair off with scissors. None of these hold the power over the vast numbers of people a voter does. None could do the damage possible at the hands of the unqualified citizen.

Or so they reasoned. Personally, I think they were overreacting. I mean, pretty much everyone can vote today, right? And things are going –

OK, maybe they weren’t overreacting.

But Adams doesn’t leave it at that. He elaborates on a solution, a counterbalance. He looks at the long game.

Power always follows Property. This I believe to be as infallible a Maxim, in Politicks, as, that Action and Re-action are equal, is in Mechanicks. Nay I believe We may advance one Step farther and affirm that the Ballance of Power in a Society, accompanies the Ballance of Property in Land.

The only possible Way then of preserving the Ballance of Power on the side of equal Liberty and public Virtue, is to make the Acquisition of Land easy to every Member of Society: to make a Division of the Land into Small Quantities, So that the Multitude may be possessed of landed Estates.

If the Multitude is possessed of the Ballance of real Estate, the Multitude will have the Ballance of Power, and in that Case the Multitude will take Care of the Liberty, Virtue, and Interest of the Multitude in all Acts of Government.

(Letter to James Sullivan, May 1776)

It’s all kinda understatement to say that the first century of American history was largely shaped by this need for land.

Some of it was primal and selfish, of course. At times, shiny rocks were in the ground or particularly nice lumber stuck up out of it. But those were the temporal motivators. The ethical Under Armour of expansion as a whole was this political – almost spiritual – paradigm.

To be a City on a Hill, one must have a hill. To be a republic – a government of-the-by-the-for-the – one must have qualified voters. The most universal way to demonstrate basic responsibility, competence, and character, was land ownership. Thus the almost sacred role of land in both the founding and expanding of this new democracy. It was, to many Framers, the most obvious and tangible measure of a man’s legitimacy, his investment, and his potential value as another voice in the national discussion.

Without widespread, relatively easy access to land, democracy wasn’t possible, and this grand experiment would fail. If democracy failed here, it effectively failed everywhere – it would, in fact, never even begin elsewhere.

Dark Ages. Tyranny and ignorance. Monsters rule the earth.

Every homestead was a 160-acre, individually-sized portion of national ideals. Its role was not asserted so much as perceived – much like many other “self-evident” truths bandied about in those days. And as if that weren’t enough, the issue wasn’t solely terrestrial.

Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever He had a chosen people, whose breasts He has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue. It is the focus in which he keeps alive that sacred fire which otherwise might escape from the face of the earth. Corruption of morals in the mass of cultivators is a phenomenon of which no age nor nation has furnished an example.

(Thomas Jefferson, Notes on Virginia, 1782)

I’m no authority on Jefferson, but you don’t know that – so let’s just play along and not make trouble, alright?

“Those who labor in the earth…”

I suppose he could have just said “farmers,” but this paints a more vivid picture to set up where he’s going. It’s not about a role in the economy or the food chain – it’s about the agency of individuals, applied not merely to ground or soil but to the “earth”. It’s a wide-angle lens on an idealized way of life – Jefferson’s strength.

“…the chosen people of God, if ever He had a chosen people…”

Wow. Jefferson getting all allusion-y up in here. The most obvious antecedent would be the Israelites of the Old Testament. Jefferson wasn’t a huge fan of biblical literalism, but that wouldn’t negate its value as a frame of reference.

The addition of “if ever he had a chosen people” may be read as emphasis (“that’s a miracle if ever I saw one!”) or a touch of skepticism (“if there are such things as miracles, this would be one”) – an ambivalence consistent with his few recorded thoughts on scripture. But the power of the image – the holy role of the Hebrew children –he utilizes quite intentionally.

It wasn’t much of a leap from Old Testament progenitors to fresh young Americans – the City on a Hill, the people whose destiny was quickly becoming manifest, and a culture who a century later would carry their “white man’s burden” well past the boundaries of the continent.

But for now the issue was land – or at least the way of life it promoted.

Farmers worked 365 days a year. Soil still needing tilling on your birthday, cows needed milked on Christmas, and no matter how sick you might be, those crops weren’t going to reap themselves. It was labor-intensive and the hours were long, and yet after doing all you could do, all day every day – you waited.

You waited for the rain. You waited for the growth. You waited for the births. You waited for the universe to do its part.

Sometimes it didn’t. Often, even when it did, it took too long and was too slow and there was no way to rush it, but many ways to ruin it. This combination of intense human application and eternal patience is inconceivable generations later. Almost nothing works that way anymore – at least not the sorts of things to which you set your hand on purpose, to carry proudly from cradle to grave.

Sometimes enough years and sufficient survival teach similar lessons in the 21st century – but they come too late to shape much more than our troubled reflections. The laboring Jefferson extols, however, produced “substantial genuine virtue” – a type of perspective and wisdom unavailable minus the requisite experiences.

You won’t find accounts of farmers going rogue in meaningful numbers, he claims. Presumably this is related to all that “virtue” and “sacred fire,” but it also seems unlikely that any successful farmer could have found the time or energy to be particularly corrupt. The natural consequences of immorality or irresponsibility would be an immediate, self-inflicted deterrent. Like playing in the traffic or juggling chainsaws, any screw-ups would be painfully self-correcting.

Agriculture… is our wisest pursuit, because it will in the end contribute most to real wealth, good morals and happiness. The wealth acquired by speculation and plunder, is fugacious in its nature, and fills society with the spirit of gambling. The moderate and sure income of husbandry, begets permanent improvement, quiet life, and orderly conduct both public and private.”

(Thomas Jefferson, Letter to George Washington, 1787)

Jefferson had a distrust of bankers, stock markets, or anything financial industry-ish – so much so that he took great personal pride in never having the foggiest idea how to make his estate solvent. (He died in substantial debt.) Farmers raised essentials. They produced raw materials which could be woven into clothing, smoked for pleasure, eaten to survive. “Real wealth.”

Bankers scribbled numbers in little books, in stuffy rooms, producing nothing, but somehow always taking from you. Farmers dealt in uncertainty, but financiers gambled. While farmers produced, money men “plundered.” The soil, properly tended, would always be there – would always prove reliable. Paper numbers and percentage points never were.

Jefferson is claiming an essential role of land beyond voter qualifications. He’s claiming it as a lifestyle – a moral anchor, social stabilizer, and the only true source of economic security. Husbandry grows in men the essential traits of a fledgling democracy – applied labor, determination, patience, and pragmatism. It’s the wisdom of the earth in the hands of the earth’s masters.

Those Enlightenment-types thought science-y thoughts, but they were still quite comfortable with a little melodramatic sheen to their carefully chosen words. I can’t imagine what it must have been like to spend twice as much time on how you say something as you did on what you were actually saying. Sounds tiring.

*ironic yawn*

I think our governments will remain virtuous for many centuries as long as they are chiefly agricultural; and this will be as long as there shall be vacant lands in any part of America. When they get piled upon one another in large cities as in Europe, they will become corrupt as in Europe.”

(Thomas Jefferson, Letter to James Madison, 1787)

Uh-oh.

As yet our manufacturers are as much at their ease, as independent and moral as our agricultural inhabitants, and they will continue so as long as there are vacant lands for them to resort to; because whenever it shall be attempted by the other classes to reduce them to the minimum of subsistence, they will quit their trades and go to laboring the earth.”

(Thomas Jefferson, Letter to Mr. J. Lithgow, 1805)

So let’s recap…

Land ownership allows the property owner to demonstrate his capability, his competence, his potential to be a useful voice – a valid voter. It suggested he was invested in the success of the nation.

Land ownership promotes solidity, character, ethereal virtues reflected in wise words and actions – valuable in and of themselves, sure, but especially necessary in a nation relying on the people themselves to provide effective leadership – directly or through their choices regarding representation.

Land must be available to meet the demands of an expanding nation. Without sufficient, arable land, the ideals on which the nation was founded lack the requisite elements to survive. It’s not an optional ingredient – it’s the eggs in the democracy omelet, the flour in the ‘Mericake.

Finally, in a nod to inconveniently unfolding realities, Jefferson argues that even the POTENTIAL of land ownership – its availability – provides an essential safety valve, a check on the industrializing leaven of Europe as it attempts to leaven the entire American loaf. That he so easily adjusts his faith to accommodate current events I leave to you to interpret as you see fit.

None of our Founders could have anticipated just how quickly this baby nation would begin filling up – the locals spawning and immigrants flowing in as fast as boats could carry them. If these fancy new ideals were going to expand with them, we needed to act quickly.

Opportunity. Responsibility. Chosen people. If it fails here, it fails everywhere. Darkness. Tyranny. Monsters rule the earth.

They were going to need more land. And looking west, it was largely taken…

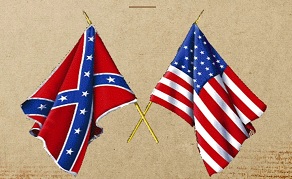

1. The North had more of everything except capable military leadership. They also weren’t fighting to defend their home states, their farms or families, or their overly-romanticized “way of life.” Despite Lincoln’s best efforts, the North kept finding ways to lose for most of the first half of the war.

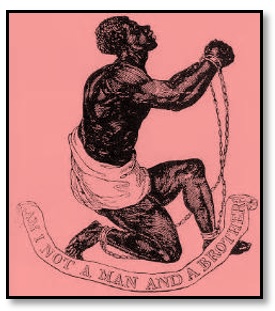

1. The North had more of everything except capable military leadership. They also weren’t fighting to defend their home states, their farms or families, or their overly-romanticized “way of life.” Despite Lincoln’s best efforts, the North kept finding ways to lose for most of the first half of the war. 1. Slavery. While not the only factor, it was by far the largest. Without it, there would have been no war. Seceding southern states issued their own “declarations” explaining the causes which impelled them to the separation. The issue? Slavery, threats to slavery, insufficient protection of slavery, criticisms of slavery. Oh, and slavery.

1. Slavery. While not the only factor, it was by far the largest. Without it, there would have been no war. Seceding southern states issued their own “declarations” explaining the causes which impelled them to the separation. The issue? Slavery, threats to slavery, insufficient protection of slavery, criticisms of slavery. Oh, and slavery. Westward Expansion: Despite the increasing tensions between the North and South over a variety of things, political compromises held the nation together most of the time. The problem was that the U.S. continued expanding at an unbelievable rate, and each new territory acquired forced anew the question of slavery.

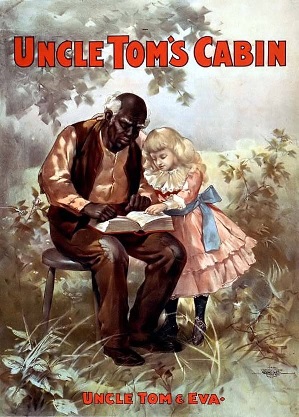

Westward Expansion: Despite the increasing tensions between the North and South over a variety of things, political compromises held the nation together most of the time. The problem was that the U.S. continued expanding at an unbelievable rate, and each new territory acquired forced anew the question of slavery.  Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): When President Lincoln met author Harriet Beecher Stowe a decade later, the story goes, he exclaimed something to the effect of “So you’re the little lady who started this great big war!” Whether this actually happened or not, the idea is sound. Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more to galvanize the North against slavery and slave-owners than any other single factor. It took nameless, faceless masses of dark chattel and made them real to readers (think Anne Frank, or that kid in the striped pajamas.)

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852): When President Lincoln met author Harriet Beecher Stowe a decade later, the story goes, he exclaimed something to the effect of “So you’re the little lady who started this great big war!” Whether this actually happened or not, the idea is sound. Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more to galvanize the North against slavery and slave-owners than any other single factor. It took nameless, faceless masses of dark chattel and made them real to readers (think Anne Frank, or that kid in the striped pajamas.) John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859): Brown was back, this time trying to start a full-blown slave revolt in Virginia. He was captured, put on trial, and sentenced to death. This is when he wrote, rather creepily, that he was “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood…”

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry (1859): Brown was back, this time trying to start a full-blown slave revolt in Virginia. He was captured, put on trial, and sentenced to death. This is when he wrote, rather creepily, that he was “now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood…” From Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address:

From Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address: It is difficult for those of you with the slightest shred of decency to appreciate how the law and politics work. They do not operate according to anything most of us consider reasonable, moral, or even explicable. In the past they didn’t have to. Those affected had little expectation of being fully informed and no real control of the outcome.

It is difficult for those of you with the slightest shred of decency to appreciate how the law and politics work. They do not operate according to anything most of us consider reasonable, moral, or even explicable. In the past they didn’t have to. Those affected had little expectation of being fully informed and no real control of the outcome. And then the South began writing the history of the war and the events which led to it. The war they’d lost. The one fought over a variety of issues, but in which slavery and its continuation were central and essential as defined by the South in the very documents they issued to justify their cause.

And then the South began writing the history of the war and the events which led to it. The war they’d lost. The one fought over a variety of issues, but in which slavery and its continuation were central and essential as defined by the South in the very documents they issued to justify their cause. What’s less tolerable is the fervent hurt and chagrin evidenced by the South’s defenders at the very suggestion that secession had ANYTHING to do with slavery. It’s not that they wish to lay out a reasoned argument, you understand – it’s that they’ve reshaped history and historiography solely through repetition and strong emotion.

What’s less tolerable is the fervent hurt and chagrin evidenced by the South’s defenders at the very suggestion that secession had ANYTHING to do with slavery. It’s not that they wish to lay out a reasoned argument, you understand – it’s that they’ve reshaped history and historiography solely through repetition and strong emotion. My favorite hockey team captain after a tough loss and horrible officiating: “There were some tough calls, but the real problem is that we didn’t take care of business in our own end. We let too many pucks get past us and didn’t take advantage of our opportunities.”

My favorite hockey team captain after a tough loss and horrible officiating: “There were some tough calls, but the real problem is that we didn’t take care of business in our own end. We let too many pucks get past us and didn’t take advantage of our opportunities.” Of course, if the real issues were states’ rights-ish, that’s not as bad. Federalism is about balance, after all, and if perhaps the South got out of balance, that’s clearly rectified now. If anything, the central government is much stronger than originally intended as a result!

Of course, if the real issues were states’ rights-ish, that’s not as bad. Federalism is about balance, after all, and if perhaps the South got out of balance, that’s clearly rectified now. If anything, the central government is much stronger than originally intended as a result! If our ideals are as flawless and our procedures as sound as we clearly wish to promote, then inequity and suffering must stem from personal or cultural failures. If America is ‘exceptional’ in the way those now in power demand we acknowledge, whatever failures have occurred within it are individual and not national. Potential solutions or cures must, logically, come from the same. Anything else is charity. Or enabling. Or corruption.

If our ideals are as flawless and our procedures as sound as we clearly wish to promote, then inequity and suffering must stem from personal or cultural failures. If America is ‘exceptional’ in the way those now in power demand we acknowledge, whatever failures have occurred within it are individual and not national. Potential solutions or cures must, logically, come from the same. Anything else is charity. Or enabling. Or corruption. I’ll close with a little Bible talkin’, since that seems to be such a motivator for those pushing a better whitewashing for our lil’uns. Whatever we may disagree on, I wholeheartedly concur that we’ve lost much in our upbringing if we feel the need to run from the wisdom found in

I’ll close with a little Bible talkin’, since that seems to be such a motivator for those pushing a better whitewashing for our lil’uns. Whatever we may disagree on, I wholeheartedly concur that we’ve lost much in our upbringing if we feel the need to run from the wisdom found in