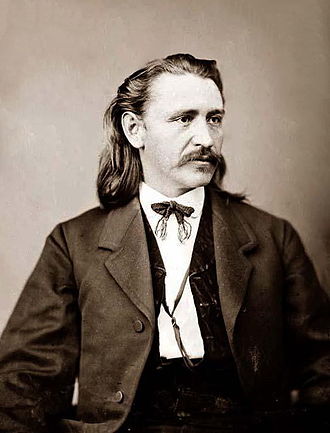

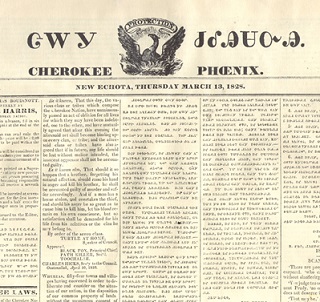

Elias C. Boudinot was the son of Elias “I Don’t Have A Middle Name” Boudinot, who’d helped to establish and edit the first Amerindian newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. Remember Sequoyah and his syllabary? Boudinot was the guy who turned it into movable type so it could be printed easily.

Elias C. Boudinot was the son of Elias “I Don’t Have A Middle Name” Boudinot, who’d helped to establish and edit the first Amerindian newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. Remember Sequoyah and his syllabary? Boudinot was the guy who turned it into movable type so it could be printed easily.

The senior Boudinot believed acculturation (assimilation into white culture) was the best hope for the survival and success of his people. He was assassinated in 1839 for his role in Indian Removal, having signed the Treaty of New EchoStar – convinced that a move to Indian Territory was inevitable and the Cherokee should at least secure the best terms possible.

I don’t know what it must be like to have your father assassinated by members of your tribe over violations of sacred beliefs, but I can’t imagine it does much for your love of the people or their traditions and values. I’m just speculating.

The rest of the younger Boudinot’s upbringing took place in Connecticut with his mother’s family – a well-off people of some status who supported Christian missionaries among the Cherokee. These weren’t the yelling and shaking godly fists types of missionaries, or the Spanish Priests variety who thought enslavement was good for the sinful savage. These were the kind of missionaries who tried to make themselves legitimately useful among those to whom they were missioning, but who also hoped to eventually change a few key traditions and values – like, say… killing those who sign away tribal lands.

The rest of the younger Boudinot’s upbringing took place in Connecticut with his mother’s family – a well-off people of some status who supported Christian missionaries among the Cherokee. These weren’t the yelling and shaking godly fists types of missionaries, or the Spanish Priests variety who thought enslavement was good for the sinful savage. These were the kind of missionaries who tried to make themselves legitimately useful among those to whom they were missioning, but who also hoped to eventually change a few key traditions and values – like, say… killing those who sign away tribal lands.

What I’m suggesting is that ECB’s later betrayal of his ancestry might not have been completely without foundation. I don’t know this for a fact, but I’m writing it with great confidence so I’m pretty sure that makes it true – especially if others stumble across this and repeat it as canon. At the very least, I don’t think it’s an unreasonable interpretation.

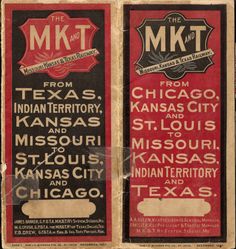

Elias C. Boudinot became in many ways the worst version of his father’s progressive vision – a political figure who worked in both Indian Territory (I.T.) and Washington, D.C., often more in support of railroads and national expansion than anything traditionally Cherokee. The excerpts below are from a letter he wrote which created quite a stir after its publication in 1879.

Elias C. Boudinot became in many ways the worst version of his father’s progressive vision – a political figure who worked in both Indian Territory (I.T.) and Washington, D.C., often more in support of railroads and national expansion than anything traditionally Cherokee. The excerpts below are from a letter he wrote which created quite a stir after its publication in 1879.

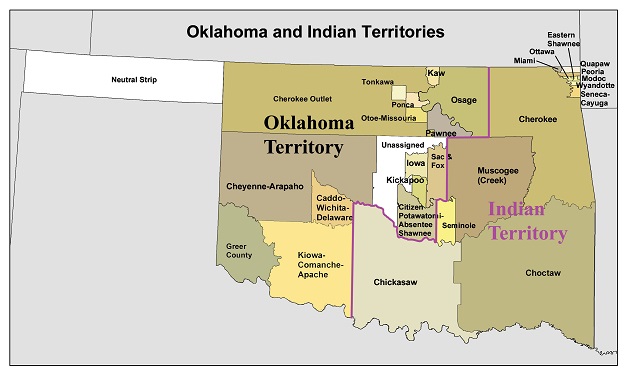

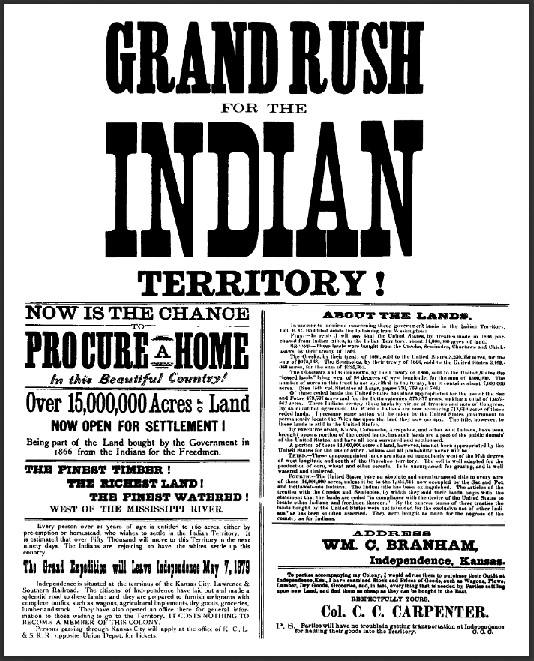

Boudinot’s argument regarding the availability of ‘unassigned lands’ in I.T. sparked a land-hungry kerfuffle and spawned ‘Boomers’ like Charles Carpenter and the unofficial ‘Father of Oklahoma’, David L. Payne.

These unappropriated lands… amount to several millions of acres and are as valuable as any in the Territory. The soil is well adapted for the production of corn, wheat and other cereals. It is unsurpassed for grazing, and is well watered and timbered.

The United States have an absolute and unembarrassed title to every acre of the 14,000,000 acres… The Indian title has been extinguished… the lands {were} ceded “in compliance with the desire of the United States to locate other Indians and freedmen thereon.”

The Reconstruction Treaties made with the various ‘Civilized Tribes’ after the Civil War include ‘freedmen’ explicitly and persistently. This choice of words was presumably intended to reinforce the postbellum reality that former slaves of the various tribes were now free, and under these treaties were to receive full rights and privileges of tribal citizenship. In this case, this meant access to land under the same terms as any other member of their respective tribes.

The Reconstruction Treaties made with the various ‘Civilized Tribes’ after the Civil War include ‘freedmen’ explicitly and persistently. This choice of words was presumably intended to reinforce the postbellum reality that former slaves of the various tribes were now free, and under these treaties were to receive full rights and privileges of tribal citizenship. In this case, this meant access to land under the same terms as any other member of their respective tribes.

By the express terms of these treaties, the lands bought by the United States were not intended for the exclusive use of ‘other Indians,’ as has been so often asserted. They were bought as much for the negroes of the country as for Indians…

Boudinot may be technically correct, but I’m not convinced he’s being completely honest. The implication that freedmen were ever intended to be granted acreage in I.T. outside the procedure for tribal land allotment is – to the best of my knowledge – ridiculous. Perhaps he’s playing on readers’ emotional reactions to the suggestion that the land ‘off limits’ to them would be so freely given to a bunch of ‘negroes.’

{The} public lands in the Territory… amount, as before stated, to about fourteen million acres.

Whatever may have been the desire or intention of the United States Government in 1866 to located Indians and negroes upon these lands, it is certain that no such desire or intention exists in 1879…

While the Massacre at Wounded Knee (which effectively ended Amerindian resistance on the Great Plains) was a decade away, Boudinot was correct that the vast majority of those who were to be ‘relocated’ had already been moved. This ‘extra land’ in Indian Territory was unlikely to be assigned anytime soon.

While the Massacre at Wounded Knee (which effectively ended Amerindian resistance on the Great Plains) was a decade away, Boudinot was correct that the vast majority of those who were to be ‘relocated’ had already been moved. This ‘extra land’ in Indian Territory was unlikely to be assigned anytime soon.

These laws practically leave several million acres of the richest lands on the continent free from Indian title or occupancy and an integral part of the public domain…

Well now he’s done it.

If these lands are public domain, they’re subject to the terms of the Homestead Act same as any other land in the west. They were pretty easy terms.

Enter Charles C. Carpenter, a former Civil War… er, ‘participant’ in various capacities, both official and not. Apparently a fan of the recently deceased George Armstrong Custer, Carpenter sported long golden curls and buckskins. A commanding officer wrote of him that “he adds great shrewdness to the reckless courage which he undoubtedly possesses.”

Enter Charles C. Carpenter, a former Civil War… er, ‘participant’ in various capacities, both official and not. Apparently a fan of the recently deceased George Armstrong Custer, Carpenter sported long golden curls and buckskins. A commanding officer wrote of him that “he adds great shrewdness to the reckless courage which he undoubtedly possesses.”

I can’t tell if that’s a backhanded compliment or genuine praise.

In any case, Carpenter built quite a resume for himself during and after the war – much of it rather difficult to actually document. To be fair, record-keeping was not a high priority in that century, and things like titles or official functions were far more subject to personal interpretation than is typical today. Think Rooster Cogburn in True Grit – officially a U.S. Marshall, also kinda working privately for Mattie Ross, sometimes subject to the rules and other times… not so much.

Add wooshy hair in slow-motion while swelling frontier music plays and you probably have a pretty good idea how Carpenter saw himself – or at least how he hoped others would see him. Like Custer or Cogburn, he seems to have simultaneously personified the best of the American West AND been a pompous faker-face who could irritate the crap out of anyone with a little civilization or education.

He was persuasive enough, though, to organize at least one big ‘boomer’ push into Indian Territory, where the limits of the government’s determination would be tested by a few brave souls willing to rough it and even risk trouble with the law to grab their little piece of the American Dream. Or at least, that was how they framed themselves.

He was persuasive enough, though, to organize at least one big ‘boomer’ push into Indian Territory, where the limits of the government’s determination would be tested by a few brave souls willing to rough it and even risk trouble with the law to grab their little piece of the American Dream. Or at least, that was how they framed themselves.

The actual ‘boomers’, I mean. Carpenter didn’t go with them. He stayed in Kansas where it was safe.

Troops from nearby Fort Reno were sent to eject these ‘boomers’ and burn their humble settlement, and they were led back to Kansas in temporary defeat. Carpenter had promised they’d try as often as necessary to accomplish their goal, but he didn’t stay long enough to follow up on this first, rather anti-climactic effort. He’d received a visit from a government official familiar with enough of his background to promise him substantial difficulty should he persist in his little settlement scheme, and Charles didn’t care to test the validity of those threats.

He bailed.

His place will be taken, however, by another Civil War veteran, this one a man who’d actually served in the army proper, and who held an advantage much more durable than charm, legal arguments, or high hopes.

David Payne believed.

RELATED POST: Boomers & Sooners, Part One ~ Last Call Land-Lovers

RELATED POST: Boomers & Sooners, Part Three ~ Who’s Your Daddy? Why, It’s David L. Payne!

RELATED POST: Boomers & Sooners, Part Four ~ Dirty Stinkin’ Cheatin’ No Good Sons Of…

RELATED POST: Boomers & Sooners, Part Five ~ Cheater Cheater Red Dirt Eater