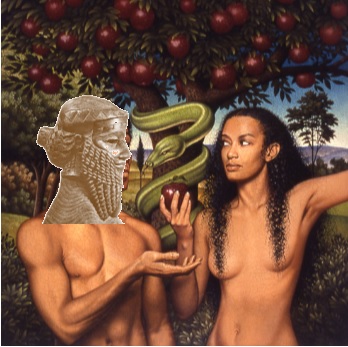

You all know this one:

{The Lord} said, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree of which I commanded you that you should not eat?”

Then the man said, “The woman whom You gave to be with me, she gave me of the tree, and I ate.”

And the Lord God said to the woman, “What is this you have done?”

The woman said, “The serpent deceived me, and I ate.”

Genesis 3:11-13 (NKJV)

It’s the first story from the first book generally agreed upon as sacred by the world’s most populous religions. In it, people screw up and quickly sacrifice their most important relationships out of selfishness, shame, and resentment. I don’t know whether the story of Adam and Eve and their Slytherin friend actually happened; I am certain, however, that it’s true.

Don’t worry – I’m not going to go all theological on you. But whatever else the Bible is, it’s a penetrant guide to our mortal hopes, fears, and foibles. It’s the ultimate anthology of sin and salvation, leaving us to debate only the details and the extent to which it should be taken literally.

Let’s fast forward a few chapters. Turns out the “blame” theme doesn’t end with humanity’s banishment from Eden:

Sarai said to Abram, “See now, the Lord has restrained me from bearing children. Please, go in to my maid; perhaps I shall obtain children by her.” And Abram heeded the voice of Sarai. Then Sarai, Abram’s wife, took Hagar her maid, the Egyptian, and gave her to her husband Abram to be his wife… So he went in to Hagar, and she conceived. And when she saw that she had conceived, her mistress became despised in her eyes.

Genesis 16:2-4 (NKJV)

When authors repeat a theme with minor variations, they’re trying to tell you something. Great literature does it, Broadway musicals do it, even sitcoms do it. Two stories, melodies, or wacky conflicts weave around one another, each echoing and expanding the other. The parallels between this passage and the account of mankind’s initial fall are striking – as are the differences.

The right clergyman could preach a Venn Diagram of these for a straight month.

Then Sarai said to Abram, “My wrong be upon you! I gave my maid into your embrace; and when she saw that she had conceived, I became despised in her eyes. The Lord judge between you and me.” So Abram said to Sarai, “Indeed your maid is in your hand; do to her as you please.” And when Sarai dealt harshly with {Hagar}, she fled from her presence.

Genesis 16:5-6 (NKJV)

As in the Garden, no one wanted to own their role in the problem. As in the Garden, none of those involved (among the humans, anyway) was entirely blameless or maniacally evil. Let’s be honest – hanging such pretty fruit nearby and naming it something like “Eternal Life” was just begging for the newbies to fail. And leaving Abram hanging for so many years after promising him so much? Men have certainly boinked around with less cause throughout history. Heck, IT WAS HIS WIFE’S IDEA.

In her defense, her entire value as a woman was on the line, and she’d been faithfully following his magical voices for a decade or so without payoff. Maybe it was time to give things a nudge? (You may remember an old joke about a man who waved off two boats and a helicopter because he believed God would save him from the flood. The twist is that those rather mundane earthly solutions WERE his promised salvation.)

Abram, Sarai, and Hagar all had good reason to be confused – perhaps even frustrated. But like many of us, each had difficulty owning their choices – their efficacy. Any genuine search for truth or improvement has to begin by accepting one’s own fallibility and ignorance. It takes humility to learn from mistakes – our own or those of others.

Sarai: “This is on you, Buddy!”

Abram: (*steps back*) “She’s your servant – I’m going to let you sort this out.”

Hagar: “None of this was my idea – I’m outta here.”

One last story. It’s told three separate times in the book of Genesis (chapters 12, 20, and 26) with minor variations.

Abraham (or Isaac) enters a new region and worries how he’ll be treated, especially since his wife is something of a hottie (remember, she still hasn’t had kids at this point). He tells whoever’s in charge that she’s his sister, which is apparently technically true – they’re related in some way. (Translations are tricky for stuff like this, and the original authors had other priorities than making life easy on future historians).

The king takes Sarai (or Rebekah) into his harem, which includes a waiting period during which God intervenes and punishes the entire household for – get this – not realizing they’d been lied to by the people God actually likes much better. This not only preserves the sanctity of the married couple but prevents God from raining down even more severe destruction on the victims of the deception, who are not God’s chosen favorites because they’re the wrong ethnicity and from the wrong region.

It was the Old Testament, people – they were harsher times; you get harsher gods.

But here’s where Abimelech (the deceived party in two of the three versions) approaches things somewhat differently than the protagonists and presumed heroes of the narratives. Having been confronted by God with the truth of the situation, he pleads his case to the Almighty, then takes concrete action:

So Abimelech rose early in the morning, called all his servants, and told all these things in their hearing…

Presumably this was so they could adjust their behavior based on this new information.

…and the men were very much afraid.

You think?

And Abimelech called Abraham and said to him, “What have you done to us? How have I offended you, that you have brought on me and on my kingdom a great sin? You have done deeds to me that ought not to be done.” Then Abimelech said to Abraham, “What did you have in view, that you have done this thing?”

Genesis 20:8-10 (NKJV)

It’s possible Abimelech is simply expressing his outrage. He has every reason to be chafed. But the narrator records his specific phrasing, and if we learn nothing else in English class, we’re inundated with examples of how authors love packing meaning into the subtleties of dialogue and background details.

Abimelech: “How have I offended you? Why would you do this, exactly? Seriously, that was messed up.”

It just seems like a much healthier, more direct way to confront a problem.

Abimelech: “So… best case scenario – what did you think would happen?”

I ask my kids variations of this question all the time.

Abraham’s response is typical of what we’ve already seen from the future Father of Nations:

And Abraham said, “Because I thought, surely the fear of God is not in this place; and they will kill me on account of my wife. But indeed she is truly my sister. She is the daughter of my father, but not the daughter of my mother; and she became my wife. And it came to pass, when God caused me to wander from my father’s house, that I said to her, ‘This is your kindness that you should do for me: in every place, wherever we go, say of me, “He is my brother.” ’ ”

In other words…

Abraham: “It was because of you people…”

Combined with…

“And besides, technically…”

Topped off with…

Abraham: “This was all God’s idea. I’d still be back in Ur chillin’.”

Abimelech’s response is interesting.

Then Abimelech took sheep, oxen, and male and female servants, and gave them to Abraham; and he restored Sarah his wife to him. And Abimelech said, “See, my land is before you; dwell where it pleases you” …

So Abraham prayed to God; and God healed Abimelech, his wife, and his female servants. Then they bore children; for the Lord had closed up all the wombs of the house of Abimelech because of Sarah, Abraham’s wife.

Genesis 20:14-18 (NKJV)

There was no extended rationalizing about what happened – no recorded complaints about the completely bogus way accountability was doled out – no lingering bitterness over the cost or headache. Abimelech had a kingdom to think of – a people to lead. He couldn’t afford to be defensive or small because he had responsibilities. Relationships. A role to fulfill.

I may infer too much, but Abimelech sounds like someone comfortable enough with who and what he is that he has little use for blame. Honesty, sure. Accountability, absolutely. But finger-pointing and petty denials? Nope. Sorry. More important things to do.

Even when he’s the one getting screwed over – unlike, say, Adam. Or Sarai. Or Abraham.

I think there’s a lesson here for classroom leadership and our relationships with difficult students, peers, or parents. I fear there’s a much larger lesson regarding my approach to society and politics.

If I’m comfortable with who I am and what I’m doing, what does that change about how I confront criticism? Opposition? Betrayal? Confusion? Is the priority fulfilling my role or defending my record? When should we pursue more complete accountability and when is it best to simply say, “here’s what I’ve got; dwell where it pleases you”?

I’m not sure I know enough to be more specific or better gage the extent to which we should take such things literally, but I know it’s on my mind and that it’s probably important.

Then again, it’s not like I can help it – you’re the ones reading and egging me on. If anything, this is all your fault. Let God be the judge!

RELATED POST: Jonah’s Education

RELATED POST: It’s Not About Them (It’s About Us)

RELATED POST: Obedience School

Do you ever start off intending to write about one thing and no matter how much you try to stay on target, you keep shooting off an entirely different direction like a blog grocery cart full of one item and with a bad wheel (*squeak lurch squeak squeak lurch*) and although you’re desperately trying to steer back to what you set out to write about, you just… can’t – at least not until you’re so close to your max word count that there’s no point?

Do you ever start off intending to write about one thing and no matter how much you try to stay on target, you keep shooting off an entirely different direction like a blog grocery cart full of one item and with a bad wheel (*squeak lurch squeak squeak lurch*) and although you’re desperately trying to steer back to what you set out to write about, you just… can’t – at least not until you’re so close to your max word count that there’s no point? I don’t write many posts about Bible stuff, or faith in general. As incoherent as my posts may be, I try to remain tethered to topics at least remotely related to public education.

I don’t write many posts about Bible stuff, or faith in general. As incoherent as my posts may be, I try to remain tethered to topics at least remotely related to public education. It’s an obsession which seems to directly counter the entire point of the New Testament. An obsession specifically condemned by the central figure of that more recent Covenant, and after whom their faith is generally named.

It’s an obsession which seems to directly counter the entire point of the New Testament. An obsession specifically condemned by the central figure of that more recent Covenant, and after whom their faith is generally named.  According to the book of Genesis, God started mankind out with much to enjoy and to do, and a single rule not to eat fruit from one particular tree. The very first temptation by the earliest manifestation of ‘Satan’ began by questioning this lone prohibition – “Did God REALLY Say…?”

According to the book of Genesis, God started mankind out with much to enjoy and to do, and a single rule not to eat fruit from one particular tree. The very first temptation by the earliest manifestation of ‘Satan’ began by questioning this lone prohibition – “Did God REALLY Say…?”

The New Testament and the arrival of Jesus Christ instead offered freedom – from the hierarchical structure of the Old Testament system, from rituals and sacrifices, and from the bondage of sin itself. The problem with freedom, though, is that you’re free. You have to figure things out and sort through options yourself. That’s great, in theory, but also terrifying and disorienting.

The New Testament and the arrival of Jesus Christ instead offered freedom – from the hierarchical structure of the Old Testament system, from rituals and sacrifices, and from the bondage of sin itself. The problem with freedom, though, is that you’re free. You have to figure things out and sort through options yourself. That’s great, in theory, but also terrifying and disorienting.  Remember the rush of shared victory you feel when your favorite team wins an important game, or the release of dopamine when you finally get past that nest of mercenaries on your X-box, and apply it to your eternity-shaping spiritual paradigm.

Remember the rush of shared victory you feel when your favorite team wins an important game, or the release of dopamine when you finally get past that nest of mercenaries on your X-box, and apply it to your eternity-shaping spiritual paradigm.  Instead we’re exhorted to “take up our cross” and follow Him – and as a bonus, if our hearts are truly pure, men will revile and persecute us and we’ll suffer a bunch, then die! We’re even specifically warned away from anyone who looks like things are going pretty well for them or who claims to have God’s will all figured out.

Instead we’re exhorted to “take up our cross” and follow Him – and as a bonus, if our hearts are truly pure, men will revile and persecute us and we’ll suffer a bunch, then die! We’re even specifically warned away from anyone who looks like things are going pretty well for them or who claims to have God’s will all figured out.  The New Testament simply doesn’t lend itself to the sorts of things politics are good at, or that people naturally want to be a part of. The Old Testament is a much easier model to emulate, and a far more entertaining system in which to be on the “right side” – preferably wreaking havoc on the “wrong.”

The New Testament simply doesn’t lend itself to the sorts of things politics are good at, or that people naturally want to be a part of. The Old Testament is a much easier model to emulate, and a far more entertaining system in which to be on the “right side” – preferably wreaking havoc on the “wrong.”