The following is a first draft for what I hope will become the follow-up to “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases. I’m sharing some of the chapters as they’re written, partly to share with you, my Eleven Faithful Followers, and partly because nothing brings out the typos, grammar errors, and other shortcomings like publishing something online. Enjoy.

FOLLOW UP: The final version of this one (and the one that ended up in the book) can be found here.

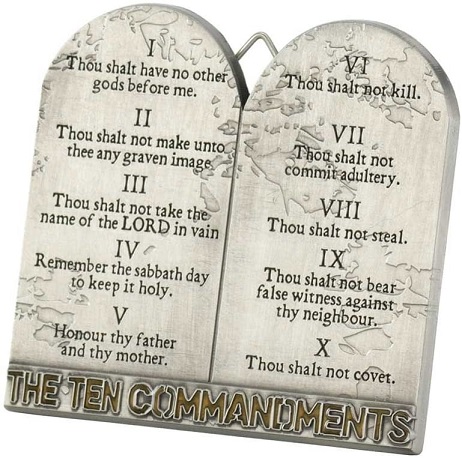

Thou Shalt Post These In Every Classroom

Three Big Things:

1. Kentucky required that the Ten Commandments be posted in all public school classrooms without comment, but with a little disclaimer underneath about them being the “fundamental legal code of Western civilization.”

2. The Court applied the “Lemon Test” and determined that the legislation had no clear secular purpose; it was thus a violation of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

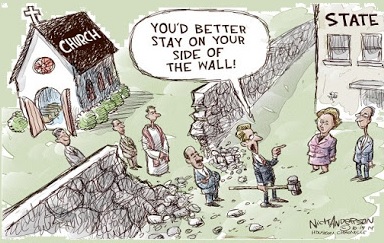

3. Whereas recent cases had dealt with efforts to support the secular education of students in religious schools without running afoul of the “wall of separation,” Stone marked a new generation of cases focused on the reverse – seeing just how far religion could be brought back into public schooling.

Background

The Supreme Court’s decision in Stone v. Graham was announced on November 17th, 1980. Less than two weeks earlier, Ronald Reagan had been elected President of the United States, initiating what would later be called the “Reagan Revolution” – a resurgence of conservative values and policies anchored in an idealized past. The events leading to Stone began years earlier, but its outcome sent a message to the faithful in the 1980s similar to that of Engel v. Vitale and Abington v. Schempp two decades before: American’s fundamental values (meaning public promotion of Christianity) were under attack by intellectual elitists… aka “liberals.” And some of them wore robes.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Stone v. Graham was announced on November 17th, 1980. Less than two weeks earlier, Ronald Reagan had been elected President of the United States, initiating what would later be called the “Reagan Revolution” – a resurgence of conservative values and policies anchored in an idealized past. The events leading to Stone began years earlier, but its outcome sent a message to the faithful in the 1980s similar to that of Engel v. Vitale and Abington v. Schempp two decades before: American’s fundamental values (meaning public promotion of Christianity) were under attack by intellectual elitists… aka “liberals.” And some of them wore robes.

Less than a month after Stone was decided, John Lennon was assassinated. In January of 1981, Reagan took office and began “making America great again.” The symbolism is purely retrospective; it’s not like the 1970s had been great for either side of the cultural divide. The U.S. had weathered Watergate, Vietnam, and a major energy crisis before succumbing to disco, of all things. Cult-leader “Reverend” Jim Jones had recently led his followers in mass suicide, the horrifying event from which the phrase “drinking the Kool-Aid” was coined. As the new year began, the U.S. was on Day 400-plus of the Iranian Hostage Crisis. Everyone knew the exact number each day because the evening news led with it every night.

The “Miracle on Ice” at the 1980 Olympics was nice, but it already felt like a LONG time ago.

In short, there are many for whom it may not have seemed like such a bad time to try to slip some old-time religion back into the classroom, and nothing was more old-time-y than the Ten Commandments.

Rules to Live By

There’s nothing like a decade or two of perceived dissolution and chaos to make law-and-order look wonderfully shiny and assuring, and the Decalogue fit the bill perfectly. It offered clear guidelines for proper living, literally set in stone, but minus the sort of detailed penalties and depressing legalistic minutia spelled out elsewhere in the Old Testament.

It didn’t hurt that it was more-or-less universally revered – Protestants, Catholics, even Jews liked it! (You know, all the REAL religions.) What more could one ask?

The State of Kentucky required that a copy of the Ten Commandments be posted on the wall of every public school classroom. The Commandments were purchased via private contributions, so no state money was used, and teachers were not required to discuss, promote, or even draw attention to the Commandments so posted. At the bottom of each copy was this explanation:

The secular application of the Ten Commandments is clearly seen in its adoption as the fundamental legal code of Western Civilization and the Common Law of the United States.

And yet, there were a few parents who for some reason thought this might violate the Establishment Clause. The case worked its way through the courts until it was accepted on appeal by the big one.

The Decision

The Court’s 5 – 4 decision was nevertheless issued per curiam, meaning “by the court.” Per curiam decisions are traditionally for situations in which there was little need to elaborate on constitutional reasoning and the Court was so united as to eliminate the need for an identifiable voice speaking for the whole. Gradually over the course of the 20th century, however, the Court began allowing concurring opinions to per curiam decisions, then dissents… and eventually it became an unacknowledged tool for avoiding personal responsibility for controversial ideas or arguments.

In other words, per curiam opinions periodically allow a degree of avoidance and misdirection from a body otherwise recognized as unflinching and unafraid.

The Court’s anonymous majority opinion revisited the three-part “Lemon Test” laid out less than a decade before in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971). Part one stated that in order to pass constitutional muster, a law must have a secular purpose to begin with. Clearly, the Court argued, that was not the case here. The Ten Commandments weren’t being used to study the evolution of written law, or in comparative religion, or even as literature or general history. They were just… there.

This is not a case in which the Ten Commandments are integrated into the school curriculum, where the Bible may constitutionally be used in an appropriate study of history, civilization, ethics, comparative religion, or the like. Posting of religious texts on the wall serves no such educational function. If the posted copies of the Ten Commandments are to have any effect at all, it will be to induce the schoolchildren to read, meditate upon, perhaps to venerate and obey, the Commandments. However desirable this might be as a matter of private devotion, it is not a permissible state objective under the Establishment Clause.

Nor was the majority impressed by the State’s “Religious values? Are they really?” defense:

The preeminent purpose for posting the Ten Commandments on schoolroom walls is plainly religious in nature. The Ten Commandments are undeniably a sacred text in the Jewish and Christian faiths, and no legislative recitation of a supposed secular purpose can blind us to that fact…

We conclude that {this legislation} violates the first part of the Lemon v. Kurtzman test, and thus the Establishment Clause of the Constitution.

Having failed the first test, there was no reason to discuss the remaining two. End of story.

The Dissent(s)

Four justices disagreed, but only one went to the trouble to elaborate as to why. Judging from his tone, Justice William Rehnquist (who’d later become Chief Justice) was shocked and a tad appalled that the Court wouldn’t simply take state legislators at face value when they explained that posting religious laws without context in every school classroom regardless of age level or subject matter was actually part of a very important historical lesson on the evolution of Occidental jurisprudence. Because isn’t that normally how lesson plans are put together – mass stapling of posters paid for by outsiders?

Rehnquist quotes from previous decisions extensively and rather effectively:

The Establishment Clause does not require that the public sector be insulated from all things which may have a religious significance or origin. This Court has recognized that “religion has been closely identified with our history and government” (Abington School District v. Schempp, 1963) and that “[t]he history of man is inseparable from the history of religion” (Engel v. Vitale, 1962). Kentucky has decided to make students aware of this fact by demonstrating the secular impact of the Ten Commandments…

What was arguably his strongest rhetorical moment, however, came in one of his footnotes:

The Court’s emphasis on the religious nature of the first part of the Ten Commandments is beside the point. The document as a whole has had significant secular impact, and the Constitution does not require that Kentucky students see only an expurgated or redacted version containing only the elements with directly traceable secular effects.

Aftermath

Stone was one of the first cases to rule that even a “passive display” of religion could nevertheless violate the Establishment Clause. It was from this reasoning the Court would subsequently take issue with certain government-sponsored Christmas displays and other state-sanctioned religious ceremonies. The Ten Commandments in particular would become a symbolic “line in the sand” on various state capital grounds or displayed in a public building or two. Consistent with the Court’s decision in Stone, decisions in those future cases would often come down to context – where were they posted, how were they presented, and why were they included?

The 1980s would see a minor explosion of cases directly or indirectly related to the “wall of separation” between religion and public education. The question of equitable facility usage became a thing – can schools who allow community groups to meet on school grounds after-hours deny the same opportunity to religious groups? (Spoiler: Nope.) Indirect aid to religious institutions via tax credits for parents, secular school supplies, or simply sending over teachers kept coming before the Court, always in slightly different forms and forcing the Court to continually revise their solutions. There was even a brief foray into “Evolution vs. Creationism” before the decade was out.

By far the most interesting cases, however, would be ever-shifting efforts to circumvent Engel, Abington, and the rest by testing one problematic element at a time. Eventually, all sorts of religious expression in public schools would be framed as “student led,” but in the 80s it started much more simply. What if schools weren’t posting commandments, reading Bible verses, or leading students in prayers? What if every day simply began with a… “moment of silence”?

Turns out that one will be hard to dispute, no matter how obvious the intent. The right was finally going to have a few wins.

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – The Ten Commandments (Part One)

RELATED POST: A Wall of Separation – The Ten Commandments (Part Two)

RELATED POST: “Have To” History – Zorach v. Clauson (1952)

The Board of Education in Champaign, Illinois, allowed a local religious organization consisting of clergy and other volunteers to come into their public schools and teach religion classes during the school day. The organization, calling itself the Champaign Council on Religious Education, offered Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish options. The classes were “voluntary,” and any expenses were paid for by the Council, not the school district or parents.

The Board of Education in Champaign, Illinois, allowed a local religious organization consisting of clergy and other volunteers to come into their public schools and teach religion classes during the school day. The organization, calling itself the Champaign Council on Religious Education, offered Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish options. The classes were “voluntary,” and any expenses were paid for by the Council, not the school district or parents. McCollum’s case reached the Supreme Court in 1947, the same year Everson v. Board of Education was decided. In Everson, the Court determined that state assistance to parents whose children rode public busses to school was fine, even though that assistance included families utilizing parochial schools. Everson was the first case of its kind to reach the Court and involved difficult questions about what the “wall of separation” meant in practice when applied to state and local government via the 14th Amendment. Plus, it hadn’t been decided at the time McCollum first began pursuing her case in the courts. It’s unlikely she or anyone else involved had even heard of it yet.

McCollum’s case reached the Supreme Court in 1947, the same year Everson v. Board of Education was decided. In Everson, the Court determined that state assistance to parents whose children rode public busses to school was fine, even though that assistance included families utilizing parochial schools. Everson was the first case of its kind to reach the Court and involved difficult questions about what the “wall of separation” meant in practice when applied to state and local government via the 14th Amendment. Plus, it hadn’t been decided at the time McCollum first began pursuing her case in the courts. It’s unlikely she or anyone else involved had even heard of it yet. When McCollum’s case reached the Supreme Court, a supportive amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief was filed by none other than the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. This group was in some ways the intellectual and spiritual descendants of those whacky Danbury Baptists who a century-and-a-half before had written to President Thomas Jefferson about the need for protection from the State. Jefferson’s response coined the phrase “a wall of separation,” which quickly became canon in interpreting the two church-state clauses of the First Amendment.

When McCollum’s case reached the Supreme Court, a supportive amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief was filed by none other than the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. This group was in some ways the intellectual and spiritual descendants of those whacky Danbury Baptists who a century-and-a-half before had written to President Thomas Jefferson about the need for protection from the State. Jefferson’s response coined the phrase “a wall of separation,” which quickly became canon in interpreting the two church-state clauses of the First Amendment. The Majority Opinion

The Majority Opinion Frankfurter’s Concurrence

Frankfurter’s Concurrence Jackson’s Concurrence

Jackson’s Concurrence Reed’s Dissent

Reed’s Dissent I’ve started putting together information and drafts for something which may or may not be titled “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation (Public School Edition). Call me wacky, but I find this stuff fascinating.

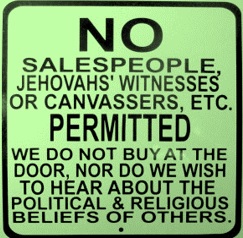

I’ve started putting together information and drafts for something which may or may not be titled “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation (Public School Edition). Call me wacky, but I find this stuff fascinating. After the Supreme Court’s decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), harassment and violence towards Jehovah’s Witnesses surged dramatically across the United States. Many felt validated and encouraged by the Court’s decision, which in their mind had essentially prioritized loyalty and being a good American over freedom of religion, speech, or association. It didn’t help that the U.S. entered World War II shortly thereafter, making patriotism and loyalty towards one’s nation and the flag representing it even more essential in the minds of many and any deviance not merely suspect, but dangerous.

After the Supreme Court’s decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), harassment and violence towards Jehovah’s Witnesses surged dramatically across the United States. Many felt validated and encouraged by the Court’s decision, which in their mind had essentially prioritized loyalty and being a good American over freedom of religion, speech, or association. It didn’t help that the U.S. entered World War II shortly thereafter, making patriotism and loyalty towards one’s nation and the flag representing it even more essential in the minds of many and any deviance not merely suspect, but dangerous. Perhaps not surprisingly, persecution only strengthened the resolve of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their kids still to have other gods before the Big One. It was a mere three years before almost the exact same case as Gobitis came before the High Court once again. This time, the results would be a tiny bit different.

Perhaps not surprisingly, persecution only strengthened the resolve of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their kids still to have other gods before the Big One. It was a mere three years before almost the exact same case as Gobitis came before the High Court once again. This time, the results would be a tiny bit different. West Virginia and other states did allow some modification of the stiff-arm salute now associated with the Nazi Party. (Presumably, it was OK to behave like fascists as long as one used a slightly different arm motion while so doing.) They also tweaked the rules concerning expulsion. Children not saluting the flag and saying the Pledge would be sent home, after which parents would be prosecuted for not having them in school.

West Virginia and other states did allow some modification of the stiff-arm salute now associated with the Nazi Party. (Presumably, it was OK to behave like fascists as long as one used a slightly different arm motion while so doing.) They also tweaked the rules concerning expulsion. Children not saluting the flag and saying the Pledge would be sent home, after which parents would be prosecuted for not having them in school. In a rather bold move, the three-judge court not only decided in favor of the Barnettes, but made no effort to justify their decision by pretending this case was in some way different than its predecessor. Instead, they simply explained their reasoning based on developments since Gobitis, along with their own interpretation of the law and the Bill of Rights. Taken together, it’s a written opinion as eloquent as anything coming from the Supremes in those days:

In a rather bold move, the three-judge court not only decided in favor of the Barnettes, but made no effort to justify their decision by pretending this case was in some way different than its predecessor. Instead, they simply explained their reasoning based on developments since Gobitis, along with their own interpretation of the law and the Bill of Rights. Taken together, it’s a written opinion as eloquent as anything coming from the Supremes in those days: The State appealed the case up the ladder (hence the reversal in the order of the names) and the Supreme Court was given an opportunity to try again. This time, they ruled 6 – 3 in favor of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The majority focused less on religious freedom for Jehovah’s Witnesses and more on freedom of speech (or lack thereof) in general. It’s not just that children of certain faiths should be free to respectfully abstain from public recitations of mandatory patriotism, they argued – it was bigger than that. There are certain core liberties which should be protected for everyone, regardless of the specific belief system or point of view involved:

The State appealed the case up the ladder (hence the reversal in the order of the names) and the Supreme Court was given an opportunity to try again. This time, they ruled 6 – 3 in favor of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The majority focused less on religious freedom for Jehovah’s Witnesses and more on freedom of speech (or lack thereof) in general. It’s not just that children of certain faiths should be free to respectfully abstain from public recitations of mandatory patriotism, they argued – it was bigger than that. There are certain core liberties which should be protected for everyone, regardless of the specific belief system or point of view involved: Barnette was a turning point for jurisprudence involving the freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Initially, the first ten Amendments were added to the new Constitution as limits on what the federal government could do or demand of individuals. While state constitutions might offer similar protections for speech, religion, etc., there was no national standard for such things until the first half of the 20th century, when the Court began utilizing the 14th Amendment (ratified just after the Civil War, in 1868) to apply the protections and ideals of the Bill of Rights to the relationship between citizens and state or local government as well.

Barnette was a turning point for jurisprudence involving the freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Initially, the first ten Amendments were added to the new Constitution as limits on what the federal government could do or demand of individuals. While state constitutions might offer similar protections for speech, religion, etc., there was no national standard for such things until the first half of the 20th century, when the Court began utilizing the 14th Amendment (ratified just after the Civil War, in 1868) to apply the protections and ideals of the Bill of Rights to the relationship between citizens and state or local government as well. The basic principle still holds – there are laws and expectations ever citizen must heed, regardless of belief system or personal creed. After Barnette, though, sincerely held religious convictions gained substantial ground in terms of what they could or couldn’t be used to justify, both in the world of public education and beyond. Also magnified was the idea that fundamental freedoms like those guaranteed in the Bill of Rights shouldn’t have to wait on legislatures or the next election to find protection – an approach which will be applied to full effect by the Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s.

The basic principle still holds – there are laws and expectations ever citizen must heed, regardless of belief system or personal creed. After Barnette, though, sincerely held religious convictions gained substantial ground in terms of what they could or couldn’t be used to justify, both in the world of public education and beyond. Also magnified was the idea that fundamental freedoms like those guaranteed in the Bill of Rights shouldn’t have to wait on legislatures or the next election to find protection – an approach which will be applied to full effect by the Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s. Several years ago, my wife and I moved to northern Indiana from Oklahoma and I started a job at a new school. Day One, first hour, I was about 30 seconds into introducing our opening activity when I was interrupted by announcements via school intercom. “Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance…”

Several years ago, my wife and I moved to northern Indiana from Oklahoma and I started a job at a new school. Day One, first hour, I was about 30 seconds into introducing our opening activity when I was interrupted by announcements via school intercom. “Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance…” I recently finished

I recently finished  In the waning years of the Great Depression, as Europe stumbled towards war, patriotism in the United States became mandatory in all but name. Many states passed laws requiring all public school students to salute the American Flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance each day, apparently assuming that nothing promotes heartfelt commitment like mandatory obeisance. If you’ve seen pictures from the era, you may notice that the standard salute looked different than it does today. Typically, it involved the right arm extended forward and upwards at a slight degree towards the flag as participants chanted in unison their devotion to the collective.

In the waning years of the Great Depression, as Europe stumbled towards war, patriotism in the United States became mandatory in all but name. Many states passed laws requiring all public school students to salute the American Flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance each day, apparently assuming that nothing promotes heartfelt commitment like mandatory obeisance. If you’ve seen pictures from the era, you may notice that the standard salute looked different than it does today. Typically, it involved the right arm extended forward and upwards at a slight degree towards the flag as participants chanted in unison their devotion to the collective. We like to imagine the Supreme Court as remaining safely beyond the pale of popular opinion or social forces, but they are at times quite human and may even read the news from time to time. The makeup of the Court evolves as well, and shortly after the Gobitis decision, it changed rather dramatically. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes retired, as did Justice McReynolds. Justice Stone, author of the sole dissent in Gobitis, was promoted to Chief Justice, and Justices Robert Jackson and Wiley Rutledge joined the Court.

We like to imagine the Supreme Court as remaining safely beyond the pale of popular opinion or social forces, but they are at times quite human and may even read the news from time to time. The makeup of the Court evolves as well, and shortly after the Gobitis decision, it changed rather dramatically. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes retired, as did Justice McReynolds. Justice Stone, author of the sole dissent in Gobitis, was promoted to Chief Justice, and Justices Robert Jackson and Wiley Rutledge joined the Court.