When my kids were little, we used to go to Bishop’s Cafeteria to eat with my dad. He was old, and old people like cafeterias – so we went.

My son would fill his tray with everything he could fit in, including that cafeteria classic – brightly colored, cubed Jello. My daughter was much pickier, but inevitably she chose the wiggly cubes as well. The boy would snarf down his selections in minutes; the girl would take hours if we let her.

It is worth noting that she didn’t usually eat the Jello.

She liked to look at it. The table would inevitably get jostled a bit, or otherwise nudged, and the Jello would wiggle. It’s what Jello does. She loved that. And, to be fair, that’s just as valid a use for Jello as any other. (Just because something is edible doesn’t mean it serves no other function – otherwise, neither houseplants nor family pets would be around long.)

But that’s not how my son saw it.

“Sis, you gonna eat that Jello?”

“No.”

“Can I have it, then?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“It’s my Jello.”

“Are you serious?”

Of course she was serious. I had to question his bewilderment, given that this scene was played out repeatedly over the years. Still, his outrage seemed to build quite genuinely, every time…

“Come on, Sis – you’re not going to eat it!”

“No.”

“But WHY?!?”

“It’s MY Jello.” And at this point, she’d usually give it an extra lil’ nudge – *wigglewigglewigglewigglewiggle*

“DAD!”

“Yes, Son?”

He’d explain, as if perhaps I’d been abroad on business the whole time, rather than sitting there at the same table while things unfolded according to sacred family tradition. I’d express my condolences, but had to concur with Sis that the Jello at issue was, in fact, HER Jello. It didn’t help his case that he’d snarfed an entire platter of foodstuffs only moments before – including a very similar chalice of… cubed Jello.

It never went well.

As the United States began to expand west, its people encountered numerous native tribes who were – to be blunt – in the damn way. Our national sin in regard to Amerindians is not that we overcame them, it’s that we did so bathed in such hypocrisy. Rather than declare war, we declared eternal friendship. We killed them in the name of peace and in pursuit of a faith built on martyrs. We took everything from them while demanding their gratitude – for our civilization, our religion, and our pitiless modernity.

To be fair, we needed the land. They had it, but… well, they weren’t really using it properly. The Plains tribes especially were the worst sort of land-wasters – hunting when hungry, gathering when gathering was useful, hanging out, carousing and eating and socializing and such…

We lacked the words to declare them hippies, but ‘utopians’ didn’t seem harsh enough. Not one single factory. Very little organized agriculture. No hospitals. No schools. Just relationships alternating with quiet reflection.

I’m overgeneralizing, of course – there were hundreds of tribes and cultures and such – but by and large, they weren’t doing proper America things with the lands they claimed as theirs. And, as with the Jello, subjected to repeated wiggling but remaining unconsumed, our frontiersmen forebears weren’t impressed by the arguments of those claiming that land ownership requires neither cultivation nor mall-building.

(And don’t even try to pretend there was no such thing as ‘owning land’. That doesn’t even make sense. That’s like saying you can’t own people – ridiculous.)

It was genuinely maddening. Let’s not overlook that. Mixed in with the greed and selfishness and prejudice and maybe even some dark damnable thoughts was palpable frustration – an almost holy outrage – that this land was being denied them by a people unwilling to do more than jiggle their Jello.

We needed that land – we deserved that land (because if having it allows us to establish worthiness, then we should have it BECAUSE we’re worthy – it makes perfect sense, if you don’t think about it too closely).

This is not just about me and mine – although it IS very much also about me and mine. We’re here as part of something bigger – something important – something holy – something democratic – something special.

Killing Indians for personal reasons wasn’t considered particularly onerous by the standards of the day. Most of the civilized world was still pretty comfortable with what would today be condemned as racial and cultural elitism. This was beyond that, though – this was brushing aside a backwards culture and a darkened people (figuratively?) to make room for progress. Light. Democracy. The New Way.

Because we NEEDED this land for settlers. For homesteaders. For citizens. Without it, there’s no progress. Without sufficient land, the whole of-the-by-the-for-the concept clogs up – it could even fail. And if American democracy fails, the new nation fails. If it fails here, it fails everywhere. Tyranny returns, darkness wins, and monsters rule the earth.

Conflict with Mexico was not much different. Their culture was nothing like most Amerindian peoples, but neither did we particularly fathom or appreciate their social structure, economic mores, or anything else – nor they ours. Perhaps outright disdain for one another played a different role than with the Natives, and certainly by that point the sheer momentum of Westward Expansion eclipsed whatever underlying values or beliefs had fueled it a generation prior, but whatever the immediate motivations, the same conviction of absolute rightness oozed from the words and letters of those pinche gabachos manifesting their destiny.

It’s not logical, but it is very human to devalue how others process their world and the goals they choose to pursue. The Natives had every opportunity to make themselves productive – to get a little schooling (hell, we offered it to them FOR FREE), learn proper civilization, even to take care of themselves through the miracles of modern agriculture. The Mexicans had plenty of chances to be, um… less Mexican.

But let’s set aside for a moment that we were inflicting antithetical values and lifestyles on a diversity of proud peoples. We’ll ignore the generations of broken treaties and outright deception. I’d like to focus on the third element of the equation – the rigged game, even should the Locals choose to play our way.

Poor tools. Bad soil. Spoiled supplies. If there’s such a thing as a “level playing field,” this wasn’t it.

They were assigned a value system and lifestyle they didn’t want, with the full weight of state and federal governments forcing compliance. They were assigned the worst land on which to practice this new system, and given inadequate tools and other supplies. The stakes were incredibly high – at best, they were expected to emulate those with the right equipment, in which case they could perhaps almost survive as second-class citizens. More likely, they would fail, starve, or simply give up – this not being a game they’d wished to play anyway. The dominant citizenry would then point to this “failure” and label them as lazy, incompetent, or otherwise flawed.

(If you didn’t know better, you’d think I was talking about how conservatives manage public education, wouldn’t you? There may be many reasons to study and enjoy history, but the last thing we want to do is to begin recognizing the variety of ways in which humanity manifests the same tendencies and plays the same games across time and place. We might have to learn from it and confront it in real life, and let’s face it – that’s awkward for everyone.)

After the Civil War, many Freedmen believed they deserved – that they had in fact been promised – “40 Acres and a Mule.” Some had actually been granted such at the unauthorized discretion of Union generals who, reasonably enough, took land from defeated plantation-owners and redistributed it to former slaves.

These few instances were reversed to smooth the transition into Reconstruction and maintain the almost cultish commitment Americans had to property rights – and, apparently, to irony. The freedmen received nothing.

Well, that’s not entirely true. They received freedom. That was a pretty big deal. But freedom to do… what? With no education, no land, no resources, no momentum – what, exactly, were their options?

Many stayed where they were, working the same land they’d been working, in exchange for food and shelter. Others left their former “masters” and wandered, either seeking loved ones from whom they’d been separated or simply wanting to go… somewhere else.

Many ended up working for white landowners under various arrangements. The South had just lost a rather brutal war – they didn’t have money to pay anyone. But food, shelter, a place to be… that they had. Eventually sharecropping and tenant farming were ubiquitous.

Freedmen didn’t have any land, or a realistic way to obtain land. Carpetbaggers from the North began establishing schools, the government had a few agencies, but overall opportunity was… limited. Just over a decade after the South surrendered the war, the North surrendered Reconstruction and brought their troops home in exchange for the Presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes.

You all remember Hayes, right? A President for whom it was worth giving up the closest the nation had ever come to realizing its founding ideals?

Yeah, me neither.

The freedman had gained everything – in theory. On paper, they were free! The men could vote! Land ownership! Education! Equality before the law! Unalienable rights, in your FACE!

But without land, or a practical way to obtain land, they couldn’t provide for themselves. The system didn’t facilitate advancement via laboring for others – just ask the Lowell Girls, the Newsies, or any ox. Freedmen (or others without land) couldn’t do the things people had been conditioned to expect as a prerequisite for suffrage – for being a ‘full American’.

Despite written law, it was ridiculously difficult for freedmen to vote. It was impossible to gain economic ground, individually or as a community. Expression is severely limited when any unpopular thought can result in loss of livelihood. How does one maintain a sense of self against so much negation? At what point do we become our labels?

That’s the suffrage part. If Jefferson was correct about the spiritual and moral benefits of “laboring in the earth,” working land belonging to another may or may not have been worth partial divine credit. In terms of vested interest in our collective national success, whatever support black Americans lent to their country came without terrestrial reciprocation.

White men who succeeded under the system believed they deserved to succeed. Most had genuinely worked hard and made good choices by the standards of the time. It was not entirely logical to see those who did not flourish as clearly undeserving – but it was entirely human. We are not, after all, overly rational beings.

We all want to be part of a meaningful system, an ordered universe, and to be justified in whatever satisfaction we draw from our efforts. Generally, ‘facts’ adjust themselves to fit our paradigms rather than the reverse. That’s not specifically a white thing – that’s a people thing.

What began as a checklist for civic participation became the default measure of a man. What was intended to protect representative government from the incompetent or slothful became an anchor on those who didn’t fit certain checklists as of 225 years ago. They were unworthy. Not quite full Americans – and thus not quite real people. Not in the ways that counted.

The issue became your state of being rather than your efforts, choices, or abilities. It was self-perpetuating and self-reinforcing. It became circular.

Eventually land would lose its status as the ultimate measure and cure-all, and we’d find something new which absolutely must be made theoretically available to all for ‘democracy’ – such as it is – to survive. This new ‘golden ticket’ would replace land in terms of both the opportunity it purports to provide and the gage by which we rank value and ability. As with land, many will feel compelled to force the façade of equity into the equation while denying the risk of large-scale success by undesirables. {Hint: it starts with an ‘E’ and rhymes with ‘zeducation’.}

But that’s a few generations away. For now, men were looking west and feeling the pull of its potential – and of theirs.

None of our Founders or Framers could have anticipated just how quickly this baby nation would begin filling up – the locals spawning and immigrants flowing in as fast as boats could carry them. Nor is it fair to judge their worldviews and prejudices entirely by the standards of our own times. We can recognize their shortcomings and even their sins without completely demonizing them.

It did mean, however, that the ideals on which the nation had been founded quickly proved problematic in their implementation. Even in the limited, white male paradigm of the day, fulfilling those ideals seemed to require more territory than we’d realized. And yet… they still seemed like such promising ideals.

We were going to need even more land, or this wasn’t going to work.

1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers.

1. Eastern Amerindians in colonial times practiced a very different sort of warfare than the large-scale, mass destruction favored by European powers. I may have mentioned how giddy I was to come across a wonderful piece by Helen Churchill Condee in Harper’s Weekly, from way back on February 23, 1901. When you combine insight, knowledge, and pithy writing, you have my heart forever.

I may have mentioned how giddy I was to come across a wonderful piece by Helen Churchill Condee in Harper’s Weekly, from way back on February 23, 1901. When you combine insight, knowledge, and pithy writing, you have my heart forever. Candee moved to Guthrie, Oklahoma, for several years, writing regularly for periodicals back east. It was around this time she published her first two books – How Women May Earn A Living and An Oklahoma Romance. The first became a landmark in women’s literature (a subject for another time) and the second – her only work of fiction out of the many successful books she’d continue to write – helped publicize and glorify life in the recently opened territory.

Candee moved to Guthrie, Oklahoma, for several years, writing regularly for periodicals back east. It was around this time she published her first two books – How Women May Earn A Living and An Oklahoma Romance. The first became a landmark in women’s literature (a subject for another time) and the second – her only work of fiction out of the many successful books she’d continue to write – helped publicize and glorify life in the recently opened territory.

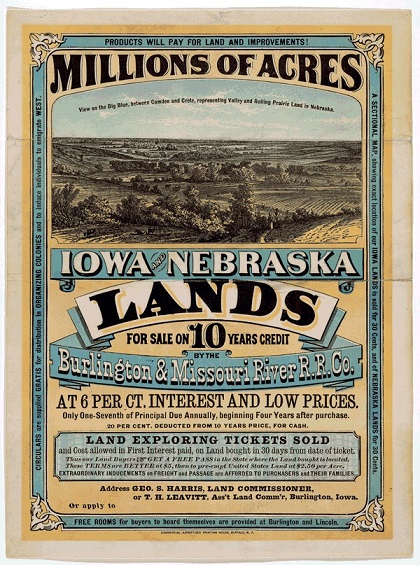

At that moment, it was still all about land – farming, growing, raising, living land. And this was it. Everything else was pretty much taken. The bar was closing and the men outnumbered the women 3 to 1. Time to make your play.

At that moment, it was still all about land – farming, growing, raising, living land. And this was it. Everything else was pretty much taken. The bar was closing and the men outnumbered the women 3 to 1. Time to make your play.  The allotment size was consistent with the Homestead Act from way back in 1862, signed by Lincoln during the Civil War. This was considered a sufficient spread to allow a homestead and plenty of planting land. A free man working without modern equipment would be unlikely to cultivate more than this productively.

The allotment size was consistent with the Homestead Act from way back in 1862, signed by Lincoln during the Civil War. This was considered a sufficient spread to allow a homestead and plenty of planting land. A free man working without modern equipment would be unlikely to cultivate more than this productively.  How many others in that generation and prior had taken their shots, staked their claims, virtually everywhere else in the West? Those waiting now were the also-rans, the coulda-beens, desperate for one last chance at stepping into the role of Yeoman Farmer in the most democratic manifestation of the ideal. Redemption? Maybe so.

How many others in that generation and prior had taken their shots, staked their claims, virtually everywhere else in the West? Those waiting now were the also-rans, the coulda-beens, desperate for one last chance at stepping into the role of Yeoman Farmer in the most democratic manifestation of the ideal. Redemption? Maybe so.