I stopped to ask him what the machine was and what it did. He told me it was a manure spreader – a ‘sh*tslinger’, he said.

Oh! It’s a big ol’ thing, isn’t it? I asked.

Well, he explained, it takes a LOT of sh*t to make stuff grow.

Isn’t THAT the truth, I thought. Always.

Farmers in the late 19th century were frustrated.

To be fair, some of their struggles were not entirely unexpected. As the west ‘filled up’ with white homesteaders, choice farmland was increasingly rare. The U.S. Government had run out of peoples to remove, and even at their most Manifestly Destined could find no justification for another war with Mexico.

The 1890 Census would soon declare the frontier ‘closed’, to the chagrin of men like Frederick Jackson Turner who believed the westward struggle against nature and deprivation both defined and strengthened American character. Things were so desperate that white guys began looking lustfully at Oklahoma as their last best hope – the same ‘Indian Territory’ (I.T.) to whom the bulk of surviving Amerindians had been forcibly removed.

The 1890 Census would soon declare the frontier ‘closed’, to the chagrin of men like Frederick Jackson Turner who believed the westward struggle against nature and deprivation both defined and strengthened American character. Things were so desperate that white guys began looking lustfully at Oklahoma as their last best hope – the same ‘Indian Territory’ (I.T.) to whom the bulk of surviving Amerindians had been forcibly removed.

I.T. had been chosen both for its distance from existing ‘civilization’ and the tacit assumption it represented the most god-forsaken plot of unloveable soil on the continent. Now it was being eyed with a desire born of desperation and a few hopeful shots of delusion. By 1889, the first sections were being opened to white settlement via land run, and eventually Oklahoma would become the 46th State of the Union.

But not yet.

As the century approached another turn, farmers across the Great Plains – even those in slightly more cooperative climes than Oklahoma’s – were enduring hard times. This was not unprecedented, but it did seem to be persisting – and advances in both literacy and communication facilitated an awareness that not everyone seemed to be sharing similar struggles.

It wasn’t always a lack of production. Many farmers across the Plains were quite successful – at least in the traditional sense. They were growing and raising more good stuff than ever before! Wheat! Corn! Cotton! Moo-cows! Chickens! Tomatoes! Quiche!

It wasn’t always a lack of production. Many farmers across the Plains were quite successful – at least in the traditional sense. They were growing and raising more good stuff than ever before! Wheat! Corn! Cotton! Moo-cows! Chickens! Tomatoes! Quiche!

But thanks to the laws of supply and demand, the more they raised, the lower the selling price. That’s great for those purchasing, but suck city for those producing. Throw in improved agriculture in Europe, and the American farmer was in a world of hurt.

As individualists, they reacted in an individually sensible, hard-working way – they looked to produce MORE.

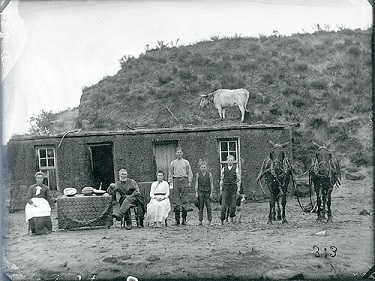

Farmers already worked 365 days a year, sun-up to sun-down. They worked on Sundays, birthdays, Christmas, and when they were sick. They labored in the earth and cared for any animals they held, enduring drought and deluge, heat waves and freezes, in hopes of coaxing forth from the earth sustenance for themselves and the world.

Farmers already worked 365 days a year, sun-up to sun-down. They worked on Sundays, birthdays, Christmas, and when they were sick. They labored in the earth and cared for any animals they held, enduring drought and deluge, heat waves and freezes, in hopes of coaxing forth from the earth sustenance for themselves and the world.

They grew and raised stuff you could eat, or wear, or – back in the day – smoke. They were useful. Heck – they were essential!

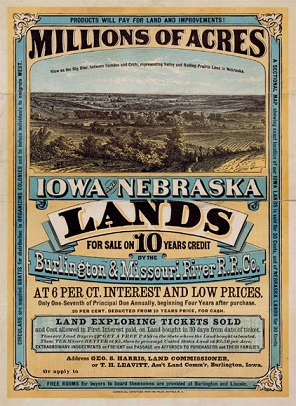

But this was a time of the ‘newer and better’ – machinery, fertilizers, and other technological wonders (“just look at this scientifically shaped point on this metal – that’s right, folks… REAL METAL – shovel!”) With ‘newer and better’, they could bring even more land into production! Purchase more acres, more machinery, more seed, more productivity – PROGRESS!

But… this meant they’d need money. Borrowed money.

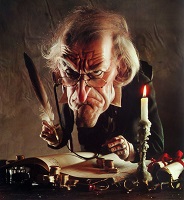

Looking east they saw a world of bankers and businessmen, of numbers and percentages, stock markets and manipulation. Men in suits, working what had already become known as “bankers’ hours” – 5 days a week minus holidays, done by mid-afternoon, and inside by the stove when it was cold or near an open window when it was hot.

They didn’t actually grow anything, or produce anything your kids could eat, or wear, or even that you could smoke, drink, or otherwise enjoy.

They didn’t actually grow anything, or produce anything your kids could eat, or wear, or even that you could smoke, drink, or otherwise enjoy.

Instead, they scribbled in little books, mysterious ciphers covered in obscure terms, and this somehow meant they got to keep part of your money. You couldn’t for the life of your loved ones tell exactly WHAT they were doing, but you knew you needed them – they held access to loans, to financing, to equipment, seed, and survival during patient years. How did THIS make sense, they wondered?

There’s a reason Dickens only a generation before had written Ebenezer Scrooge as a money lender (albeit a British one) – what could be more cold-hearted and useless in this life?**

It wasn’t JUST the banks, of course – farmers felt taken advantage of by railroads, the operators of grain elevators and silos, and pretty much anyone with money or influence in a system they instinctively believed warped in favor of the Ebenezers, but lacked the time or worldviews to master themselves.

So the banks loaned money to the farmers, and the farmers purchased land and equipment. And it worked, in a sense – they became even harder-working, even more productive. They raised even MORE stuff you could eat, smoke, and wear!

Which meant, of course, that prices went even LOWER. In some cases, less than was necessary to break even. Some couldn’t pay back their loans. So, they renegotiated, perhaps borrowed more, bought more, raised more…

Which meant, of course, that prices went even LOWER. In some cases, less than was necessary to break even. Some couldn’t pay back their loans. So, they renegotiated, perhaps borrowed more, bought more, raised more…

See a pattern?

For the first time in American history, it seemed, a large demographic was doing everything right – they were honest, hard-working, productive, and responsible – and they were failing.

Individuals had of course failed before, despite their best efforts, but individual failure can always be blamed on fate, or sin, or some personal shortcoming perhaps hidden in the mix. When the most idealized segment of American Dreamers – those whom Jefferson declared “the chosen people of God” – were facing bankruptcy and starvation, however…

Either malicious players were subverting the system, or the system was broken. They weren’t quite ready to go full Tom Joad (“Damn right, I’m bolshevisky!”), but they were – for the first time en masse – willing to call on the one earthbound entity big enough to tackle perceived corruption and necessary correction on such a grand scale. Those who most clearly defined ‘individualism’ in the American psyche began talking, and joining together, to petition their government for a redress of grievances.

The Populist Party was born.

The Populist Party was born.

They wanted what in their minds would be a return to a level (or fertile?) field. Government regulation or control of railroads, grain storage, even telegraphs – not to make things ‘easier’, but to make things ‘fair’. (The railroads and other owners likely quibbled over the precise definition of that term in such circumstances.)

They also wanted to turn bi. Not just themselves, but the entire country.

That’s probably best covered next time.

RELATED POST: Singing Bi, Bi For Our Money Supply…

RELATED POST: Follow The Yellow Brick Road

RELATED POST: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part One

RELATED POST: Sam Patch (Part One)

**I should, um… clarify for any of my creditors who might be reading this that these are not MY sentiments, of course. These are the approximated impressions of a thousand long-dead homesteaders. I love everyone the same and value our varied contributions to the Great American Melting Pot of Commerce.

Also, I’m expecting a check and should be caught up by Monday.

In keeping with their love of all things dainty, the French introduced the metal frame, lighter and sturdier. Unfortunately, the large wooden wheels and lack of any sort of shock-absorbing mechanism led to another unflattering moniker: the “bone-shaker” – less foppish than ‘dandy-horse,’ but still unlikely to facilitate worldwide acceptance and marketability.

In keeping with their love of all things dainty, the French introduced the metal frame, lighter and sturdier. Unfortunately, the large wooden wheels and lack of any sort of shock-absorbing mechanism led to another unflattering moniker: the “bone-shaker” – less foppish than ‘dandy-horse,’ but still unlikely to facilitate worldwide acceptance and marketability. The ‘Safety Bicycle’ allowed an even greater top speed than the ‘Ordinary’. More importantly, it suddenly made the bicycle easy to ride, fairly safe to steer, easier to control, lighter, and – as production increased to accommodate the wider customer base – less expensive than anything comparable prior.

The ‘Safety Bicycle’ allowed an even greater top speed than the ‘Ordinary’. More importantly, it suddenly made the bicycle easy to ride, fairly safe to steer, easier to control, lighter, and – as production increased to accommodate the wider customer base – less expensive than anything comparable prior.  There are bicycles to suit pretty much any type of rider today – any gender, race, nationality, or income level – but by and large they’re all traceable back to that first ‘Safety’. I suppose we should pay appropriate homage to its ancestors as well – but many are rather awkward to consider.

There are bicycles to suit pretty much any type of rider today – any gender, race, nationality, or income level – but by and large they’re all traceable back to that first ‘Safety’. I suppose we should pay appropriate homage to its ancestors as well – but many are rather awkward to consider.  Suddenly something of great potential but limited use, realistic only for a few, became accessible. The experience reached for by a select minority in prior generations was suddenly not only possible, but intoxicating. It was fun. It was freeing. And it was so good for you – body, mind, and soul.

Suddenly something of great potential but limited use, realistic only for a few, became accessible. The experience reached for by a select minority in prior generations was suddenly not only possible, but intoxicating. It was fun. It was freeing. And it was so good for you – body, mind, and soul.

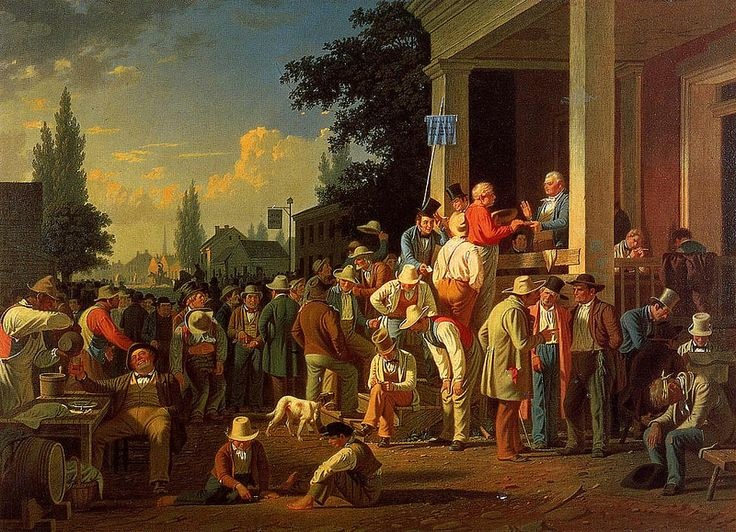

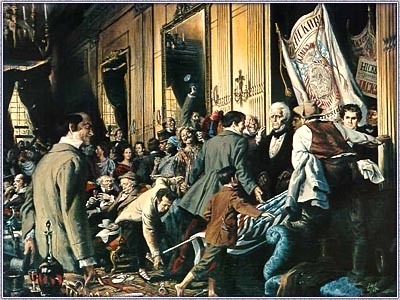

To celebrate this ‘victory of the common man’, Jackson broke with the restrictive traditions of his predecessors and threw open his inaugural celebration at the White House to all comers. It wasn’t HIS victory, after all – it was THEIR victory. Why not let THEM celebrate it as fully as anyone?

To celebrate this ‘victory of the common man’, Jackson broke with the restrictive traditions of his predecessors and threw open his inaugural celebration at the White House to all comers. It wasn’t HIS victory, after all – it was THEIR victory. Why not let THEM celebrate it as fully as anyone? Sam Patch jumped off of cliffs near waterfalls, off of the topmost masts of ships, and from other daunting heights – often into the narrowest of survivable apertures, disciplining body and breathing precisely to allow him to emerge unharmed.

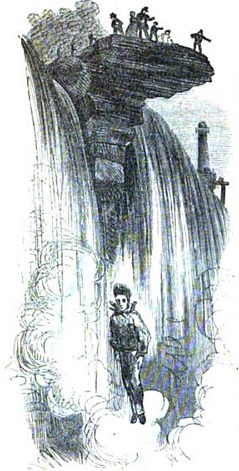

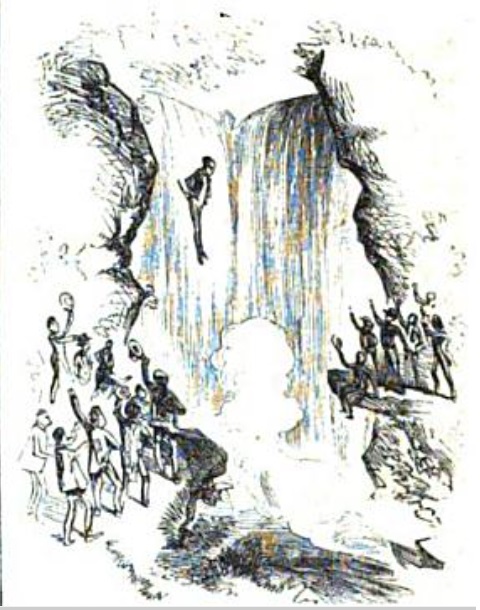

Sam Patch jumped off of cliffs near waterfalls, off of the topmost masts of ships, and from other daunting heights – often into the narrowest of survivable apertures, disciplining body and breathing precisely to allow him to emerge unharmed.  I may dig the Ramones, but I’d never invite them to dinner among proper company. I love the reckless abandon of some of my students, but I’m not sure I’d risk putting them in charge of anything potentially life-altering for myself or those around them.

I may dig the Ramones, but I’d never invite them to dinner among proper company. I love the reckless abandon of some of my students, but I’m not sure I’d risk putting them in charge of anything potentially life-altering for myself or those around them.

However stunning the surroundings, these were necessarily utilitarian times. You didn’t come to Pawtucket if things in your life had gone according to plan; the remnants who found work in the mills were either without a male head of house, or stuck with one of little use. You came because you needed work, and Pawtucket was happy to oblige.

However stunning the surroundings, these were necessarily utilitarian times. You didn’t come to Pawtucket if things in your life had gone according to plan; the remnants who found work in the mills were either without a male head of house, or stuck with one of little use. You came because you needed work, and Pawtucket was happy to oblige.  Besides offsetting his costs, the fee was designed to screen out ne’er-do-wells. The park was designed for the ‘right’ kind of people, who were far more likely to both appreciate and take care of the area. Free admission, he feared, would allow the dregs and drunkards to spoil the space. Their inability to pay was indicative of far more than income level – it was a tag of behavior and education.

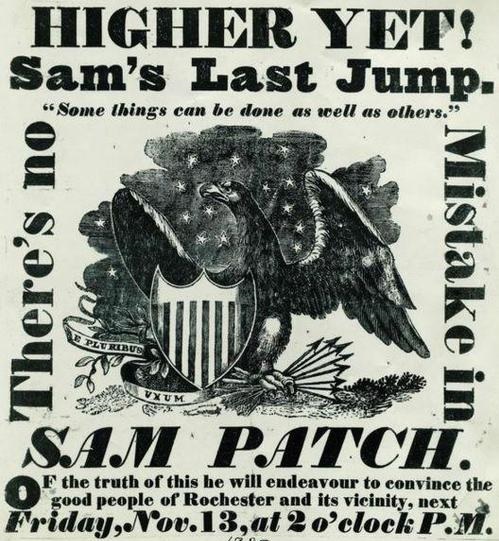

Besides offsetting his costs, the fee was designed to screen out ne’er-do-wells. The park was designed for the ‘right’ kind of people, who were far more likely to both appreciate and take care of the area. Free admission, he feared, would allow the dregs and drunkards to spoil the space. Their inability to pay was indicative of far more than income level – it was a tag of behavior and education.  On November 13, 1829, Sam made his last jump. Something went horribly wrong. It may have been the drinking or a related difficulty, but descriptions from those witnessing the event suggest he died in mid-air from something internal. His body positioning gave way and he fell limply for at least half of the 125 feet he spent in the air, striking the water with an impact which would have been fatal had he still been alive.

On November 13, 1829, Sam made his last jump. Something went horribly wrong. It may have been the drinking or a related difficulty, but descriptions from those witnessing the event suggest he died in mid-air from something internal. His body positioning gave way and he fell limply for at least half of the 125 feet he spent in the air, striking the water with an impact which would have been fatal had he still been alive. Land was a big deal when our little experiment in democracy began. Why?

Land was a big deal when our little experiment in democracy began. Why?  So, in order to assure that everyone’s political voice is more or less equal, we’re going to have to deny a political voice to some – to those without the ability to provide for themselves. Otherwise, the entire representative system may be undermined through the ability of the wealthy to manipulate the indigent.

So, in order to assure that everyone’s political voice is more or less equal, we’re going to have to deny a political voice to some – to those without the ability to provide for themselves. Otherwise, the entire representative system may be undermined through the ability of the wealthy to manipulate the indigent. No help here from the ‘Father of the Constitution’. Apparently handing power over to men without land leads to either a tyranny of the masses (mob democracy) or a system in which the ignorant are led about by the manipulations of the wealthy and power-hungry.

No help here from the ‘Father of the Constitution’. Apparently handing power over to men without land leads to either a tyranny of the masses (mob democracy) or a system in which the ignorant are led about by the manipulations of the wealthy and power-hungry. Keep in mind this was a new country – a baby nation. The Declaration was as much a Birth Certificate as a break-up letter, and our forebears were trying something entirely new. They were idealists, sure – but they were also educated, and realists, and had some idea how people tend to people-ize.

Keep in mind this was a new country – a baby nation. The Declaration was as much a Birth Certificate as a break-up letter, and our forebears were trying something entirely new. They were idealists, sure – but they were also educated, and realists, and had some idea how people tend to people-ize. Adams probably talked too much, but I do love how he steps his audience through his reasoning. It’s very Socrates, very Holmes, very Bill Nye the Government Guy. Franklin may have been the poster child of the Enlightenment in the New World, but Adams was its lesson planner and edu-blogger.

Adams probably talked too much, but I do love how he steps his audience through his reasoning. It’s very Socrates, very Holmes, very Bill Nye the Government Guy. Franklin may have been the poster child of the Enlightenment in the New World, but Adams was its lesson planner and edu-blogger. Power always follows Property. This I believe to be as infallible a Maxim, in Politicks, as, that Action and Re-action are equal, is in Mechanicks. Nay I believe We may advance one Step farther and affirm that the Ballance of Power in a Society, accompanies the Ballance of Property in Land.

Power always follows Property. This I believe to be as infallible a Maxim, in Politicks, as, that Action and Re-action are equal, is in Mechanicks. Nay I believe We may advance one Step farther and affirm that the Ballance of Power in a Society, accompanies the Ballance of Property in Land.