Ernie Pyle (1900-1945) was a journalist specializing in bringing the normal to intimate life through the written word.

Ernie Pyle (1900-1945) was a journalist specializing in bringing the normal to intimate life through the written word.

He was a self-tortured soul in many ways – never content with staying in one place, but perpetually longing for home while traveling. He traveled the United States several times over, writing reflective pieces usually focused on unexpected encounters, and the quirky specifics of characters he discovered – who somehow became everymen for readers of all castes.

When World War II began, Pyle became what was then a very odd sort of war correspondent. He went to where the war was, but he wrote about people. Real soldiers, instead of the Captain America types otherwise put forth in the name of patriotism.

No, he didn’t write about all of the war. He didn’t even attempt to capture the true horrors – even had he wished or been able, the censors never would have allowed it, nor the public wanted it despite thinking they did.

But he made every mother, sister, wife, or other loved one back home feel like he was writing about their boy – their soldier. He made the lowest grunt feel like he was doing something worth doing in tangible, personal ways.

Here’s to the power of the written word.

His most famous column then and since tells a true story of a fallen soldier and the respect paid by the men who served with him. I’m posting it in full here without any sort of permission or rights to any of it, because… the internet.

The Death of Captain Waskow

AT THE FRONT LINES IN ITALY, January 10, 1944 – In this war I have known a lot of officers who were loved and respected by the soldiers under them. But never have I crossed the trail of any man as beloved as Capt. Henry T. Waskow of Belton, Texas.

Capt. Waskow was a company commander in the 36th Division. He had led his company since long before it left the States. He was very young, only in his middle twenties, but he carried in him a sincerity and gentleness that made people want to be guided by him.

“After my own father, he came next,” a sergeant told me.

“He always looked after us,” a soldier said. “He’d go to bat for us every time.”

“I’ve never knowed him to do anything unfair,” another one said.

I was at the foot of the mule trail the night they brought Capt. Waskow’s body down. The moon was nearly full at the time, and you could see far up the trail, and even part way across the valley below. Soldiers made shadows in the moonlight as they walked.

Dead men had been coming down the mountain all evening, lashed onto the backs of mules. They came lying belly-down across the wooden pack-saddles, their heads hanging down on the left side of the mule, their stiffened legs sticking out awkwardly from the other side, bobbing up and down as the mule walked.

The Italian mule-skinners were afraid to walk beside dead men, so Americans had to lead the mules down that night. Even the Americans were reluctant to unlash and lift off the bodies at the bottom, so an officer had to do it himself, and ask others to help.

The first one came early in the morning. They slid him down from the mule and stood him on his feet for a moment, while they got a new grip. In the half light he might have been merely a sick man standing there, leaning on the others. Then they laid him on the ground in the shadow of the low stone wall alongside the road.

I don’t know who that first one was. You feel small in the presence of dead men, and ashamed at being alive, and you don’t ask silly questions.

We left him there beside the road, that first one, and we all went back into the cowshed and sat on water cans or lay on the straw, waiting for the next batch of mules.

Somebody said the dead soldier had been dead for four days, and then nobody said anything more about it. We talked soldier talk for an hour or more. The dead man lay all alone outside in the shadow of the low stone wall.

Then a soldier came into the cowshed and said there were some more bodies outside. We went out into the road. Four mules stood there, in the moonlight, in the road where the trail came down off the mountain. The soldiers who led them stood there waiting. “This one is Captain Waskow,” one of them said quietly.

Two men unlashed his body from the mule and lifted it off and laid it in the shadow beside the low stone wall. Other men took the other bodies off. Finally there were five lying end to end in a long row, alongside the road. You don’t cover up dead men in the combat zone. They just lie there in the shadows until somebody else comes after them.

The unburdened mules moved off to their olive orchard. The men in the road seemed reluctant to leave. They stood around, and gradually one by one I could sense them moving close to Capt. Waskow’s body. Not so much to look, I think, as to say something in finality to him, and to themselves. I stood close by and I could hear.

One soldier came and looked down, and he said out loud, “God damn it.” That’s all he said, and then he walked away. Another one came. He said, “God damn it to hell anyway.” He looked down for a few last moments, and then he turned and left.

Another man came; I think he was an officer. It was hard to tell officers from men in the half light, for all were bearded and grimy dirty. The man looked down into the dead captain’s face, and then he spoke directly to him, as though he were alive. He said: “I’m sorry, old man.”

Then a soldier came and stood beside the officer, and bent over, and he too spoke to his dead captain, not in a whisper but awfully tenderly, and he said:

“I sure am sorry, sir.”

Then the first man squatted down, and he reached down and took the dead hand, and he sat there for a full five minutes, holding the dead hand in his own and looking intently into the dead face, and he never uttered a sound all the time he sat there.

And finally he put the hand down, and then reached up and gently straightened the points of the captain’s shirt collar, and then he sort of rearranged the tattered edges of his uniform around the wound. And then he got up and walked away down the road in the moonlight, all alone.

After that the rest of us went back into the cowshed, leaving the five dead men lying in a line, end to end, in the shadow of the low stone wall. We lay down on the straw in the cowshed, and pretty soon we were all asleep.

Recommended Reading – Ernie Pyle’s War: America’s Eyewitness to World War II (James Tobin)

Recommended Reading – Here Is Your War: Story of G.I. Joe (Ernie Pyle)

The story of Joan of Arc forces historians to deal with overtly spiritual claims and potentially miraculous outcomes in ways historians do not generally wish to do. We’ll cover the role of religion in the most general ways, if absolutely necessary, but we DON’T LIKE TO TALK ABOUT IT IF WE DON’T HAVE TO.

The story of Joan of Arc forces historians to deal with overtly spiritual claims and potentially miraculous outcomes in ways historians do not generally wish to do. We’ll cover the role of religion in the most general ways, if absolutely necessary, but we DON’T LIKE TO TALK ABOUT IT IF WE DON’T HAVE TO.  Immutable internal organs or not, how can you tell Joan’s story without pondering her faith? Her voices? She was either crazy with a healthy side of lucky, a very effective liar, or God spoke to her and sent her on a miracle-laden mission to save France from the English. The idea God could like France is problematic enough – but successful wars based on divine visions? Is that something we wish to encourage?

Immutable internal organs or not, how can you tell Joan’s story without pondering her faith? Her voices? She was either crazy with a healthy side of lucky, a very effective liar, or God spoke to her and sent her on a miracle-laden mission to save France from the English. The idea God could like France is problematic enough – but successful wars based on divine visions? Is that something we wish to encourage? If we’re going to acknowledge the hypocrisy and cruelty done in the name of God by early Spanish explorers confronting local Amerindians, let’s recognize the good intentions and legitimate faith of many others in similar situations. If we’re going to explain the cultural destruction done by Anglo-American missionaries to the tribes in their purview, let’s be a bit more vocal about the role of faith driving Samuel Worcester and his nameless ilk who served among the Natives with little reward in this life.

If we’re going to acknowledge the hypocrisy and cruelty done in the name of God by early Spanish explorers confronting local Amerindians, let’s recognize the good intentions and legitimate faith of many others in similar situations. If we’re going to explain the cultural destruction done by Anglo-American missionaries to the tribes in their purview, let’s be a bit more vocal about the role of faith driving Samuel Worcester and his nameless ilk who served among the Natives with little reward in this life.  As we approach modern times, it makes for a rather lopsided view of Presidential paradigms when we discuss foreign policy through every lens but the one most-cited from the Big Podium. “For we must consider that we shall be as a City Upon a Hill…” said John Winthrop in 1630 – a sentiment echoed, reworked, expanded, and cited over and over and over and over by men deciding whether or not we put our best in harm’s way in hopes of spreading that light a little further, or at least holding back the darkness a little longer.

As we approach modern times, it makes for a rather lopsided view of Presidential paradigms when we discuss foreign policy through every lens but the one most-cited from the Big Podium. “For we must consider that we shall be as a City Upon a Hill…” said John Winthrop in 1630 – a sentiment echoed, reworked, expanded, and cited over and over and over and over by men deciding whether or not we put our best in harm’s way in hopes of spreading that light a little further, or at least holding back the darkness a little longer.

That’s not actually the stumbling block you might think teaching high school in the 21st century. Nothing locks the minutiae of your subject into permanent recall like explaining it repeatedly throughout the years, and almost anything that doesn’t stick is easily researched when necessary. We’re still trying to get them to bring a pencil and check the class website periodically; there’s little danger they’ll without warning probe such historical depths that I end up academically cowed.

That’s not actually the stumbling block you might think teaching high school in the 21st century. Nothing locks the minutiae of your subject into permanent recall like explaining it repeatedly throughout the years, and almost anything that doesn’t stick is easily researched when necessary. We’re still trying to get them to bring a pencil and check the class website periodically; there’s little danger they’ll without warning probe such historical depths that I end up academically cowed.  Charles’s daddy, Charles VI (nice system, right?) was insane – even for royalty – and may not have been his daddy at all. The dear Queen was thought to be having an affair with the Duke of Orleans, aka the King’s brother, and he may have been Charles VII’s biological father. That would explain in part why the Queen was so cooperative with England when it came time to designate an official heir to the throne; she signed off on Henry VI holding that honor.

Charles’s daddy, Charles VI (nice system, right?) was insane – even for royalty – and may not have been his daddy at all. The dear Queen was thought to be having an affair with the Duke of Orleans, aka the King’s brother, and he may have been Charles VII’s biological father. That would explain in part why the Queen was so cooperative with England when it came time to designate an official heir to the throne; she signed off on Henry VI holding that honor.  It’s also the kind of thing which makes historians crazy, you understand. It’s just so awkward to deal with the supernatural in an academic context, especially given the typical disconnect between those book-learnin’ types and people of faith. We’d rather not talk about it at all.

It’s also the kind of thing which makes historians crazy, you understand. It’s just so awkward to deal with the supernatural in an academic context, especially given the typical disconnect between those book-learnin’ types and people of faith. We’d rather not talk about it at all. Faith becomes a happy fluke of background rather than a key component – as if King just happened to sit next to someone randomly on the bus who ended up playing some key role we never saw coming, or left his coat too close to the oven and accidentally invented penicillin. As if taking up the call of ministry – of spreading the Word of God to the downtrodden and fighting for justice – made a nice placeholder before changing careers and fighting for civil rights.

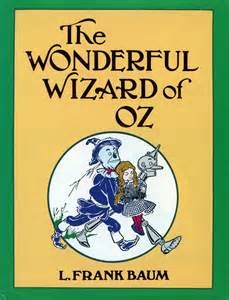

Faith becomes a happy fluke of background rather than a key component – as if King just happened to sit next to someone randomly on the bus who ended up playing some key role we never saw coming, or left his coat too close to the oven and accidentally invented penicillin. As if taking up the call of ministry – of spreading the Word of God to the downtrodden and fighting for justice – made a nice placeholder before changing careers and fighting for civil rights. In 1900, L. Frank Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a children’s book he wasn’t convinced would do particularly well – not compared to his fabulous Mother Goose and Father Goose collections a few years prior. Turns out it was a hit, and spawned multiple stage versions – usually musicals – and thirteen written sequels by Baum.

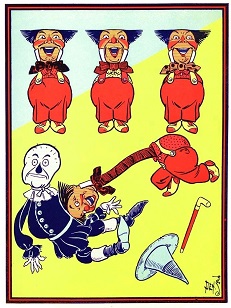

In 1900, L. Frank Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a children’s book he wasn’t convinced would do particularly well – not compared to his fabulous Mother Goose and Father Goose collections a few years prior. Turns out it was a hit, and spawned multiple stage versions – usually musicals – and thirteen written sequels by Baum.

The Tin Man = Northeastern Factory Workers. Having slaved away under dehumanizing conditions for so long, they’d essentially lost their souls – their hearts – the parts which make us most human. Upton Sinclair would capture this less festively a few years later in The Jungle, a book he intended to be about the factory-driven destruction of the human spirit and instead ended up being about how gross sausage is. Meat-packing was reformed; factory labor continued to kill the human spirit for another few generations.

The Tin Man = Northeastern Factory Workers. Having slaved away under dehumanizing conditions for so long, they’d essentially lost their souls – their hearts – the parts which make us most human. Upton Sinclair would capture this less festively a few years later in The Jungle, a book he intended to be about the factory-driven destruction of the human spirit and instead ended up being about how gross sausage is. Meat-packing was reformed; factory labor continued to kill the human spirit for another few generations.  The Yellow Brick Road = The Gold Standard. It’s an almost sacred path to the Emerald City, but one fraught with inconsistency and danger. There are pitfalls and surprises, and even substantial gaps prohibiting all but the most creative travelers for going forward. But, when you add…

The Yellow Brick Road = The Gold Standard. It’s an almost sacred path to the Emerald City, but one fraught with inconsistency and danger. There are pitfalls and surprises, and even substantial gaps prohibiting all but the most creative travelers for going forward. But, when you add…

On the other hand, there are plenty of events which even the most creative mind can’t reasonably tie to history or populism. The Quadlings who lack arms but fire their heads at you on long necks are a fascinating obstacle, and the fragile ‘china people’ are far more poignant once you drop the weak ‘unreconstructed South’ connection. And how many varieties of ‘the little people’ (or field mice or Winkies or…) can one book have before it no longer makes sense to label them all with the same Jacksonian value?

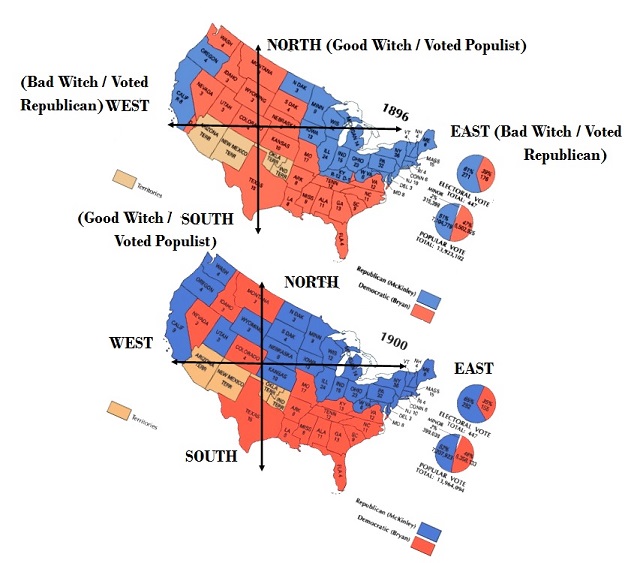

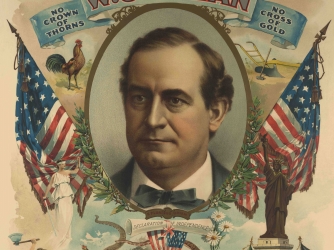

On the other hand, there are plenty of events which even the most creative mind can’t reasonably tie to history or populism. The Quadlings who lack arms but fire their heads at you on long necks are a fascinating obstacle, and the fragile ‘china people’ are far more poignant once you drop the weak ‘unreconstructed South’ connection. And how many varieties of ‘the little people’ (or field mice or Winkies or…) can one book have before it no longer makes sense to label them all with the same Jacksonian value? The Populist Party reached their zenith in the 1890’s. Although they won state and local elections here and there, before and after this decade, their only real shot at the Presidency came in the Elections of 1896 and 1900. Both times they ran William Jennings Bryan as their candidate, and both times the Democratic Party gave in and joined them in the nomination.

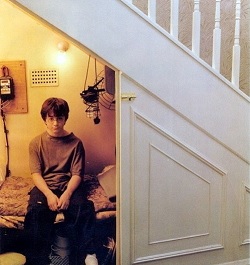

The Populist Party reached their zenith in the 1890’s. Although they won state and local elections here and there, before and after this decade, their only real shot at the Presidency came in the Elections of 1896 and 1900. Both times they ran William Jennings Bryan as their candidate, and both times the Democratic Party gave in and joined them in the nomination. I mean, Harry Potter was safe and secure at the Dursley’s under the stairs – literally and completely. No harm could come to him. As the series progressed, he grew increasingly autonomous and faced greater and greater danger. Finally, released even from the rules of Hogwarts or the direction of Dumbledore – completely and totally independent – he frickin’ DIES!

I mean, Harry Potter was safe and secure at the Dursley’s under the stairs – literally and completely. No harm could come to him. As the series progressed, he grew increasingly autonomous and faced greater and greater danger. Finally, released even from the rules of Hogwarts or the direction of Dumbledore – completely and totally independent – he frickin’ DIES! Not that most American farmers in the late 19th century were pondering such abstractions. Mostly they’d joined their voices – and their votes – to demand a few basic policy changes to compensate for what they perceived as gross imbalance in the economic order of things. They didn’t see themselves as wanting ‘help’ so much as fighting to remove cancers in the system.

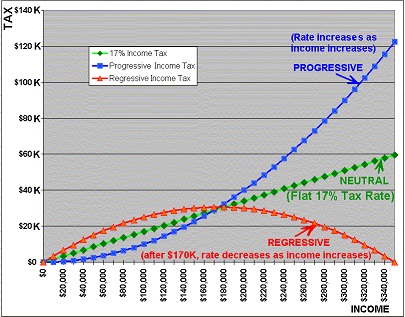

Not that most American farmers in the late 19th century were pondering such abstractions. Mostly they’d joined their voices – and their votes – to demand a few basic policy changes to compensate for what they perceived as gross imbalance in the economic order of things. They didn’t see themselves as wanting ‘help’ so much as fighting to remove cancers in the system. The Populists wanted a weighted system. If you made $10,000 this year, you pay little, or nothing. You made $50,000? Ten percent. $250,000? Twenty percent. $1,000,000? Fifty percent. Those making the most were still left with more than everyone else, and those making the least were freed from the burden of paying at all.

The Populists wanted a weighted system. If you made $10,000 this year, you pay little, or nothing. You made $50,000? Ten percent. $250,000? Twenty percent. $1,000,000? Fifty percent. Those making the most were still left with more than everyone else, and those making the least were freed from the burden of paying at all.  If you’re a bi… cycle, you have two wheels.

If you’re a bi… cycle, you have two wheels. Silver is valuable and not at all common, but it’s far more plentiful than its friend gold. The change would be dramatic. More money in circulation lowers the value of each dollar – counterintuitively helping those with less money and especially those in debt.

Silver is valuable and not at all common, but it’s far more plentiful than its friend gold. The change would be dramatic. More money in circulation lowers the value of each dollar – counterintuitively helping those with less money and especially those in debt. The food quickly draws attention and Max offers him a dollar for one of the slices. He accepts.

The food quickly draws attention and Max offers him a dollar for one of the slices. He accepts.  He sells most of the first box, but things quickly slow. Lowering the price to $1.00 helps a little, but it still looks like he’ll be stuck with 9 or 10 boxes of pizza with ten minutes to go. He panics and drops to 50 cents a slice… then a quarter… and manages to move enough that he’s only losing a little money for his troubles.

He sells most of the first box, but things quickly slow. Lowering the price to $1.00 helps a little, but it still looks like he’ll be stuck with 9 or 10 boxes of pizza with ten minutes to go. He panics and drops to 50 cents a slice… then a quarter… and manages to move enough that he’s only losing a little money for his troubles.