Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About… the “XYZ Affair”

Three Big Things

1. France was mad because the U.S. was making nice with England, who France had only recently helped them break away from and who France hated most of the time anyway.

2. U.S. efforts to make nice with France led to serious drama when French representatives (code names “X,” “Y,” and “Z”) made demands the U.S. contingent found offensive.

3. The resulting kerfuffle led to a “Quasi-War” abroad and more pronounced divisions between political parties at home before being resolved by a new round of diplomacy and a new treaty. The dispute also prompted the Federalists to push through the infamous Alien and Sedition Acts (which didn’t turn out all that well).

Background

If you’ve seen Hamilton (or at least listened to the soundtrack), you might be surprised to learn that many of the characters and events portrayed were based on real people and events in American history. Seriously, there should have been a note on the program or something to that effect. It would have added a whole other dimension to the experience.

In any case, I refer you to one of the highlights of the second act, “Cabinet Battle #2”:

The issue on the table: France is on the verge of war with England. Now do we provide aid and troops to our French allies, or do we stay out of it? … Secretary Jefferson, you have the floor, sir…

Jefferson, as you may recall, thought it was a complete no-brainer that the U.S. should jump in and assist France. French aid had tipped the balance in the Revolutionary War and their rhetoric was rooted in the same Enlightenment ideals that inspired the colonies to rebel in the first place. Hamilton thought getting involved was a horrible idea, particularly since the folk with whom they’d actually signed a treaty (the King and Queen) were dead at that point, beheaded by French revolutionaries. President Washington agreed with Hamilton, and in the very next number (“it must be nice… it must be nice… to have Washington on your side…”) the nation’s first two political parties were formed – right there on stage. It wasn’t the beginning of tensions over how the new nation should be run, but it certainly helped clarify and solidify the sides.

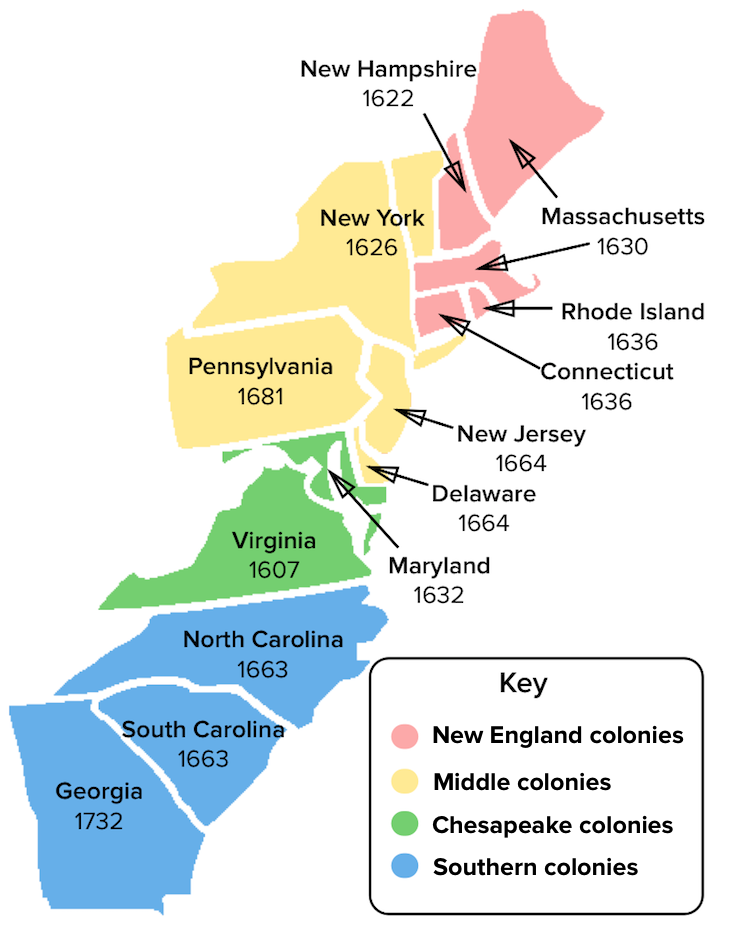

The Federalists (think Alexander Hamilton) were pushing for a strong central government and a more unified nation. Despite the recent Revolutionary War, Federalists still tended to see the world through English eyes. It was the Federalists who’d pushed for the Constitution (which replaced the much looser Articles of Confederation) and who relied on the “three branches” system to keep the government checked and balanced. If taken to the extreme, their approach to the Constitution was that anything it didn’t strictly prohibit was probably OK.

The Anti-Federalists, better known as the Democratic-Republicans (who didn’t officially include “Southern M*****-F******” as part of their title), were less enthused about strong central government. They worried that the young nation would fall back into the same patterns and problems they’d had under King George. Democratic-Republicans loved the revolutionary fervor of the French and believed that agriculture and local control were the keys to extending and strengthening the enlightened, independent nature of their new country. The Constitution gave government specific functions and powers, and anything beyond that was a leap into corruption and self-destruction. Historians often refer to this group as the “Jeffersonian Republicans” because, you know… Jefferson.

How to handle France wasn’t the ONLY issue dividing these emerging parties, but it was pretty high on the list.

Jay’s Treaty (1794)

Right after giving France their promise ring, however, Uncle Sam** slid right back into making goo-goo eyes with his ex, England. Washington and other Federalists were more pragmatic than they were idealistic; they had little interest in endless conflict with the world’s most powerful nation. They signed a treaty resolving several points of contention: the British agreed to pull out of the Northwest Territory and to leave American shipping alone (although that one didn’t exactly last) while the U.S. paid off some outstanding debts to British merchants. Both sides compromised a bit on shared boundaries. Perhaps most importantly, the treaty laid the groundwork for a positive trading relationship with England.

It’s amazing how many things can be worked out when there’s money to be made.

France saw this as a betrayal of all they’d thought they meant to the U.S., particularly after they’d sacrificed so much to help the young nation win its independence… from the very nation it was now making all cuddly with! France and England had been in recurring conflict since roughly the Neolithic Era, so Uncle Sam’s insistence that they were just friends (albeit with benefits) rang hollow. France began attacking American shipping, which hurt America’s feelings and kinda ruined how nice it was that England had finally stopped doing it.

In the middle of this madness, George Washington decided not to run for a third term in 1796. (“One last time… we’ll teach them how to say goodbye…”). The unenviable task of following the Father of the Nation into office fell to John Adams with Thomas Jefferson as VP, which was tricky since they were from different political parties – Adams was a Federalist, and Jefferson, well… was not.

The Adams Tightrope

President John Adams wanted to patch things up with France but without alienating England. He wasn’t the towering figure Washington had been and often made decisions based on how he thought things should work instead of how they did.

To be fair, Washington had struggled on this front as well. Before leaving office, he’d appointed Charles Pinckney as the U.S. “Minister to France.” It wasn’t a great match. Pinckney was a staunch Federalist from an essentially aristocratic background – the exact sort of person the French were gleefully beheading on a regular basis at the time. Adams hoped to do better.

He conferred with his VP, Jefferson, who suggested sending Madison – a Democratic-Republican with revolutionary street cred and who knew how to speak liberté, égalité, and fraternité. Instead, Adams chose the safer political path and selected more Federalists – the party who hated France to begin with and couldn’t relate to them at all. They arrived in Paris disgusted with the people, the politics, and the culture in general – not the ideal foundation for diplomacy. The French Foreign Minister, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, originally refused to see them. Eventually he sent word through intermediaries that a meeting might be arranged if the Americans agreed in advance to pay off all claims made by American merchants against France, loan France a ton of money at rock-bottom interest rates, and offer Talleyrand a substantial bribe just to get things going.

In better dynamics, these might have served as a starting point for under-the-table negotiations. As things were, it merely offended and annoyed the American coterie. They wrote back to President Adams, who in turn informed Congress that things weren’t going well and that maybe they should start preparing for the possibility of war. Not wanting to stir things up more than they already were, or risk the safety of his representatives in France, Adams substituted letters – W, X, Y, and Z – for the names of the French go-betweens. The subsequent kerfuffle, then, could just as easily have become known as the ABC Affair, the WXYZ Conflict, or the Beta Epsilon Gamma Kappa Shenanigans. He also withheld numerous details of exactly what was going badly, informing them merely that the French were being uncooperative and things could get ugly.

Well… uglier.

Let Me Be Frank(ophile) With You

France had by this time closed its ports to ships from any nation not totally “Team France” and had granted permission to French vessels to capture and search any ship they suspected of carrying British goodies – which could be any of them. Congress nevertheless insisted on getting the full TMZ report before taking further action. It passed resolutions and called Adams all sorts of bad names (although that last part wasn’t exactly new). Eventually, Adams released the letters from his representatives in France, including the demands made by X, Y, and Z.

The Democratic-Republicans simply couldn’t believe anything negative about their revolutionary brethren across the ocean. Surely Adams was lying, or the emissaries had misunderstood, or – and this one was a crowd favorite – Talleyrand’s demands were a natural result of Adam’s push for a military buildup, despite those two things having occurred in the opposite order, many months apart. (No sense letting a little thing like objective reality interfere with a good political barrage.)

American outrage was about what one would expect for a generation still drunk on the patriotic fervor of its own revolution. “Millions for defense but not one cent for tribute!” cried the masses. War was never officially declared, but this “Quasi-War” was definitely a few shoves and swear words past being “at peace.”

À La Réflexion…

Talleyrand had by this point realized he’d miscalculated and things weren’t going the way he’d hoped. He began scrambling to reopen negotiations with the U.S. while navigating revolution at home which was becoming increasingly unpredictable and bloody. Napoleon was rapidly gaining power as well, and while he loved a good scrap as much as anyone, the General was more interested in using France’s claim on Louisiana Territory (which was technically owned by Spain at the time) to help finance war in Europe.

President Adams sent new representatives to France, thus averting a real war. They eventually reached a new agreement – the Convention of 1800. (It’s also called the Treaty of Mortefontaine, but seriously – who even wants to try saying that, let alone remembering it?)

Hostilities ceased. France gave back America’s boats and the U.S. agreed to reimburse owners for any losses incurred as a result. Perhaps most importantly, France and the U.S. agreed to be trading besties again, although the U.S. was not required to quit seeing England in order to do so. This was to be something of an “open partnership.” As long as the brides didn’t have to share a bed or anything, they’d ignore one another and make it work.

Why It Matters

Public backlash to the Federalist handling of the affair contributed to the election of Thomas Jefferson, which in turn led to the Louisiana Purchase, the establishment of the U.S. Military Academy, and the end of the (legal) slave trade in the U.S. While it’s likely most of this would have occurred with or without Jefferson in the White House, the specifics likely would have unfolded quite differently, and it’s impossible to say what THAT might have looked like.

The XYZ Affair was the first major foreign policy dilemma faced by the young United States. It presented a question they’d be faced with many times over the coming centuries – when is it better to fight on principle and when does it make more sense to compromise in order to keep things running smoothly and peacefully The treaties with England and France helped the young nation continue building its economy, which over time became a major source of strength and influence (and remains so today).

Perhaps most importantly, repeated clashes over which foreign powers to support (and to what extent) led to the passage of the infamous Alien and Sedition Acts. These you should already know about because (a) they’re relatively easy to understand and remember and (b) they don’t even sound boring. If anything, the moniker oversells them a bit.

How To Remember This

The most important things about the XYZ Affair weren’t really the details of the situation itself but what it revealed about the U.S. at the time and its impact on the nation going forward. It highlighted some of the key differences between the two major political parties (despite many of the Founding Fathers going to great lengths to avoid parties existing to begin with) as well as the growing strength and influence of the U.S. in world affairs. It led to the Quasi-War, the Alien and Sedition Acts, and renewed peace with France (without sacrificing peace with England). The U.S. slung enough testosterone to demonstrate it wished to be treated like one of the big kids while going to great lengths to avoid actual war.

The jilted lover analogy hinted at above isn’t without its problems, but it’s tawdry and inappropriate – just like France and their Democratic-Republican mistresses. Anyone horrified by the comparison is probably a British sympathizer just like the Federalists with all their rules and order and financial security. The Jeffersonians, on the other hand, were all about freedom and slogans and running naked through arable fields of enlightened rule.

What You’re Likely To Be Asked

This one lends itself readily to either multiple choice questions (with “The XYZ Affair” as the correct answer) or prompts asking about challenges confronting the young nation, particularly in reference to foreign affairs. It also comes up regularly in questions about early political parties, often as an example of issues over which they disagreed.

The Texas eighth grade TEKS include this:

(5) History. The student understands the challenges confronted by the government and its leaders in the early years of the republic and the Age of Jackson. The student is expected to… (C) explain the origin and development of American political parties… (E) identify the foreign policies of presidents Washington through Monroe…

Most other state standards include similar rhetoric – political parties, foreign policy, economic stability, etc.

APUSH, too, loves it some XYZ Affair. One of the primary themes – “American in the World (WOR)” seems tailor-made for discussing this event:

Diplomatic, economic, cultural, and military interactions between empires, nations, and peoples shape the development of America and America’s increasingly important role in the world.

Learning Objective ‘L’ is equally applicable:

Explain how and why political ideas, institutions, and party systems developed and changed in the new republic.

Numerous content standards connect in some way, two quite directly:

War between France and Britain resulting from the French Revolution presented challenges to the United States over issues of free trade and foreign policy and fostered political disagreement. (KC-3.3.II.B)

Political leaders in the 1790s took a variety of positions on issues such as the relationship between the national government and the states, economic policy, foreign policy, and the balance between liberty and order. This led to the formation of political parties – most significantly the Federalists, led by Alexander Hamilton, and the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. (KC-3.2.III.B)

How To Sound Like You Know More Than You Do

If you can keep track of 80% of the details and interwoven issues involved in the XYZ Affair, you don’t have to shoot any higher. It’s legitimately a tough topic to keep straight and knowing your basics is as impressive as you need to get.

~~~~~~~~

**The term “Uncle Sam” didn’t come along for a few more years, but you know exactly who I mean. Don’t be difficult.

Given my penchant for delusions of grandeur, I opted not to commit to much this summer other than attending a single AP English institute and gradually working through a long list of “to do” stuff around the house. My hope was to make noticeable progress on a book I kinda laid the groundwork for years ago when I began adding “Have To” History articles to this site.

Given my penchant for delusions of grandeur, I opted not to commit to much this summer other than attending a single AP English institute and gradually working through a long list of “to do” stuff around the house. My hope was to make noticeable progress on a book I kinda laid the groundwork for years ago when I began adding “Have To” History articles to this site.

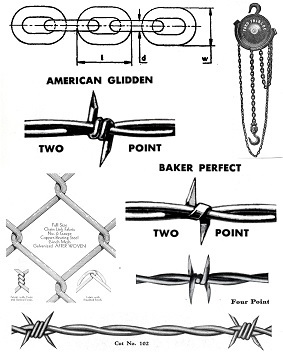

There are barbed wire museums in nearly a dozen different states. That’s right – museums devoted exclusively (or at least primarily) to the origins and impact of pokey wires in all its many varieties. The Oklahoma Cowboy Museum boasts over 8,000 varieties of prickly steel yarn, while the Devil’s Rope Museum in McLean, Texas, promises “everything you want to know about barbed wire and fencing tools.” There are several collections in and around DeKalb, Illinois, the birthplace of barbed wire, but it’s the Kansas Barbed Wire Museum which makes the grandest claims and boasts the most extensive curated exploration of this marvelous innovation.

There are barbed wire museums in nearly a dozen different states. That’s right – museums devoted exclusively (or at least primarily) to the origins and impact of pokey wires in all its many varieties. The Oklahoma Cowboy Museum boasts over 8,000 varieties of prickly steel yarn, while the Devil’s Rope Museum in McLean, Texas, promises “everything you want to know about barbed wire and fencing tools.” There are several collections in and around DeKalb, Illinois, the birthplace of barbed wire, but it’s the Kansas Barbed Wire Museum which makes the grandest claims and boasts the most extensive curated exploration of this marvelous innovation. In the meantime, demand for beef was rising. Soldiers insisted on eating from time to time and all that meat has to come from somewhere. After the war, a prosperous and victorious North wanted steak for dinner. Creative cross-breeding eventually produced a fairly hearty steer which was nevertheless edible – the Texas Longhorn. Railroads connecting the west to markets in the northeast didn’t quite reach Texas, so the age of the great cattle drives was born. Despite its eternal popularity in TV and movie westerns, the era of “git along little doggie” was really only about two decades long – from the 1850s to mid-1870s. By the 1910s… nothing.

In the meantime, demand for beef was rising. Soldiers insisted on eating from time to time and all that meat has to come from somewhere. After the war, a prosperous and victorious North wanted steak for dinner. Creative cross-breeding eventually produced a fairly hearty steer which was nevertheless edible – the Texas Longhorn. Railroads connecting the west to markets in the northeast didn’t quite reach Texas, so the age of the great cattle drives was born. Despite its eternal popularity in TV and movie westerns, the era of “git along little doggie” was really only about two decades long – from the 1850s to mid-1870s. By the 1910s… nothing. This nasty little innovation shifted the balance of power in the west considerably. Pretty much anyone could easily stake out and claim any section of land they wished, whether they legally owned it or not. Sure, you could sneak in and cut the wires, but unlike wooden fences they could be repaired and replaced just as quickly. You could try to go over, under, or through, but the wire itself discouraged this by its very nature. Barbed wire wasn’t the only reason homesteaders and private property took over the west, but it was arguably the deciding factor. As to cattle drives, yes, the railroads finally reached Texas. There were also a few brutal winters in the 1880s which killed tons of livestock. While less dramatic, there’s no denying the impact of wave after wave of desperate settlers now armed with the ability to slice the frontier into private little homesteads defended by cheap, durable, pokey wire fence.

This nasty little innovation shifted the balance of power in the west considerably. Pretty much anyone could easily stake out and claim any section of land they wished, whether they legally owned it or not. Sure, you could sneak in and cut the wires, but unlike wooden fences they could be repaired and replaced just as quickly. You could try to go over, under, or through, but the wire itself discouraged this by its very nature. Barbed wire wasn’t the only reason homesteaders and private property took over the west, but it was arguably the deciding factor. As to cattle drives, yes, the railroads finally reached Texas. There were also a few brutal winters in the 1880s which killed tons of livestock. While less dramatic, there’s no denying the impact of wave after wave of desperate settlers now armed with the ability to slice the frontier into private little homesteads defended by cheap, durable, pokey wire fence. There’s no substitute for actual historical details and legitimate reasoning, but sometimes we want to dangle something a bit more profound out there and hope it catches the teacher’s imagination. The trick is not to push it further than you can back up with actual thought and substance – let them be thrilled at the potential you’re showing, not dismayed by your grandiose nonsense.

There’s no substitute for actual historical details and legitimate reasoning, but sometimes we want to dangle something a bit more profound out there and hope it catches the teacher’s imagination. The trick is not to push it further than you can back up with actual thought and substance – let them be thrilled at the potential you’re showing, not dismayed by your grandiose nonsense.