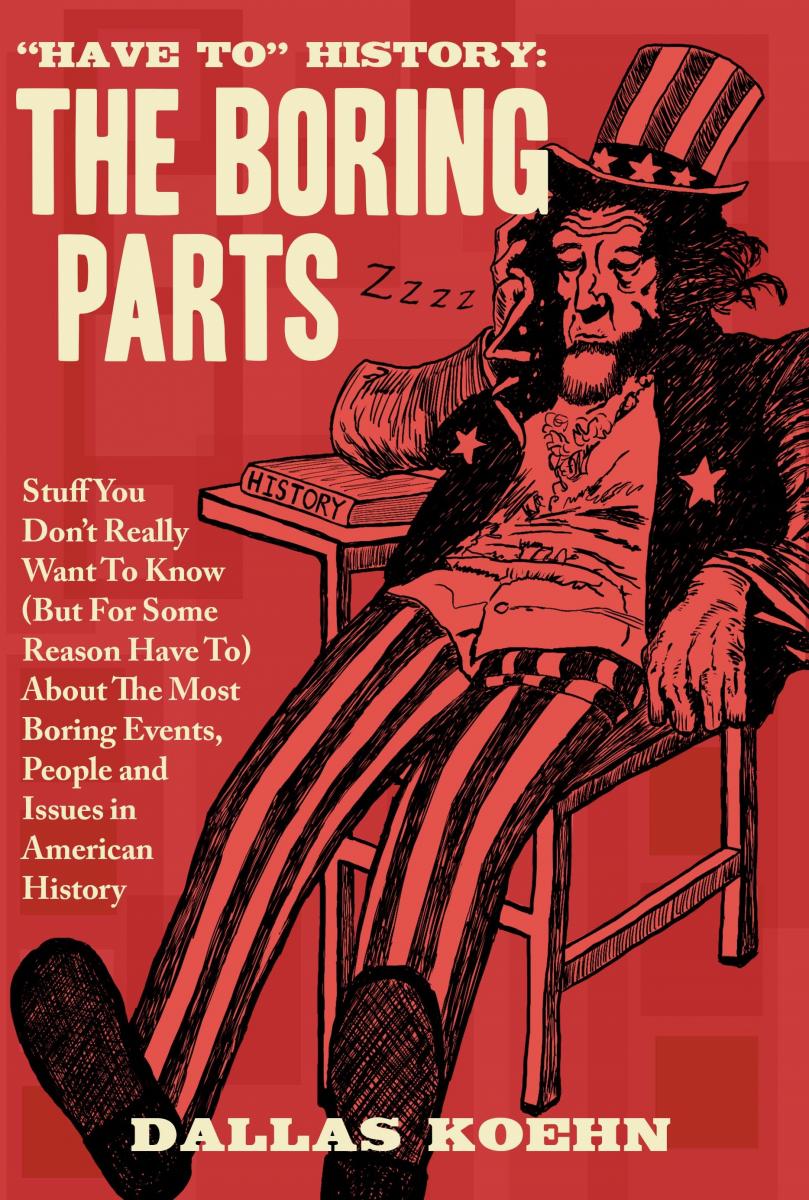

NOTE: This post and its sequel are from the rough draft of a book I’m hoping will be called something like “Have To” History: Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About The Most Boring Events, People, and Issues in American History.

As is generally the case with the drafts I post here, the final version will presumably be tightened up substantially and better edited. Your comments along the way are very much welcomed.

The 1950s – Because The Sixties Had To Come From Somewhere (Part One)

Three Big Things:

1. The 1950s are largely remembered as a time of prosperity and “cultural homogeneity.” Nevertheless, the major issues of the 1960s were poking through everywhere.

2. The explosion of new “suburbs” (like Levittown) was facilitated by more highways and more automobiles. White families fled big cities for protected pockets of all-white schools, churches, shopping, and front lawns that all looked the same.

3. On a larger scale, workers and their families moved from the “Rust Belt” of the northeast to the “Sun Belt” of the south and west in pursuit of better employment opportunities. This move was facilitated by highways and cars as well, along with advancements in the modern miracle of air conditioning.

Introduction

The 1950s are an easily brushed-over decade, whether you’re rushing to get through someone else’s curriculum before “the test” or a lover of history browsing titles at your local bookstore or online.

As part of a formal curriculum, the 50s have the unenviable task of following World War II – which is kind of like booking Led Zeppelin as your opening act but hoping the audience stays for your one-man avant-garde banjo extravaganza. Even teachers who manage to get past “the last good war” before state testing or the AP Exam are anxious to get to the 1960s, where most of the important stuff is naturally engaging all on its own – sex, drugs, rock’n’roll, civil rights, hippies, war protests (and a war to go with them), MLK, JFK, LBJ, Malcolm X, Woodstock, “the pill,” Brown Power, the American Indian Movement, women’s rights – even men on the moon (yes, really).

Sure, we’d like to get to the Reagan Revolution and 9/11, but the Sixties managed to make even stage musicals naughty and blasphemous. And there were Sea Monkeys. Why would we ever move on?

For adults interested in history, it’s almost as bad. Browsing the shelves at your local bookstore or scrolling through Amazon search results, how often do you stop and exclaim, “Hey… post-war suburban development!” There are too many far more tantalizing topics to grab the eye, and no one wants to be the guy on the subway reading The Rise of the Sunbelt: How the Interstate Highway System and Modern Air Conditioning Impacted Twentieth Century Migration Patterns – as if your social life didn’t have enough problems already.

(Thankfully, the book you’re currently reading is a proven status magnet. Currently, everyone in the room either wants you or wants to be you, so play it cool and just keep reading… like you’re too deep in learning to care.)

The 1950s, however, have plenty to add to the conversation – and not just the parts about the Cold War, the G.I. Bill, and the birth of modern rock’n’roll. Let’s see if we can unborify a few of the most neglected or easily overlooked features of the decade before you blindly rush into all the violence, nudity, and social transformation of its successor.

The “Exciting” Parts of the 1950s

Despite its reputation (or lack thereof), there were numerous important history-ish things going on in the 1950s which you probably already know about, even if you don’t realize it.

The Cold War was easily the biggest. This half-century staring contest between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. was going strong by the time all those post-WWII babies started to boom. With it came anticommunist hysteria topping even the “red scare” of the previous generation. All those Congressional committees investigating authors and the film makers and McCarthy with his supposed list of “known Communists” working for the State Department? That was all the 1950s.

The Rosenbergs were executed in 1953 for (apparently) passing along U.S. atomic know-how to the Russians. Those same Russians launched Sputnik in 1957, prompting the creation of NASA in the U.S. and all sorts of panic that American children didn’t know enough math or science. (Sometimes it really does take a rocket scientist.)

There were many less-dramatic-but-still-pretty-important results of the Cold War, such as the National Defense Education Act (1958). This provided financial aid for college students and boosted funding for math and science in high schools. It was the first meaningful foray of the federal government into public education and the basic approach proved so successful that it never went away: if the federal government offers states enough money to do X, Y, or Z, they essentially insert themselves as controlling partner in what were previously state functions (at least according to the Constitution). If states want the money, they have to follow the federal rules and adapt federal priorities.

Who’s a good state? Does someone want federal funding? Hmmm? Heel, state – heel!

Speaking of “sharing” as a means of control, don’t forget the Truman Doctrine (1947), under which the U.S. spends zillions of dollars every year propping up foreign “democracies” with American troops, money, and motivational posters. (The name is periodically updated to reflect whoever’s in office, but its substance hasn’t changed much in 75 years.) In 1954, President Eisenhower popularized the “domino theory” – the idea was that if communism was allowed to take hold anywhere in the world, the surrounding nations would soon fall to it as well. Capitalism and democracy, on the other hand, often required overwhelming military force to implement, as if they were for some reason less attractive to the rest of the world.

Weird, right?

American foreign policy was thus dramatically and forever altered. Rather than wait until U.S. interests were actually threatened, the military could now be sent anywhere in the world – locked, loaded, and overflowing with cash and lifestyle advice – to intervene wherever Uncle Sam thought it might be fun or profitable. It turned out to be surprisingly easy to justify just about anything in the name of someone else’s “freedom” or “democracy” or “unrestricted oil supply.” Besides, you wouldn’t want the godless communists to win, would you?!

This “domino theory” which would be one of the primary justifications for U.S. involvement in Vietnam a decade later was already being cited as justification for the millions spent in the 1950s to finance the war against communism in Indochina. In the meantime, there was a Korean “conflict” to tie everyone over – like a prequel or an appetizer. At least we got M*A*S*H out of the deal. (Rest in peace, Captain Tuttle.)

The modern Civil Rights Movement commonly associated with the 1960s began in the 1950s as well. The Supreme Court decided Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and began the long, messy push towards school desegregation. (It’s possible we’ll still get there someday.) Rosa Parks refused to change seats on the bus in 1955, which in turn sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1956. A young reverend by the name of Martin Luther King, Jr., who just happened to pastor a church in the area, added his voice to the protests and soon became the most recognizable face, name, and voice of the entire movement – all before New Year’s Day, 1960.

There are a few other things we usually remember easily enough. The G.I. Bill, which helped returning soldiers go to school or start small businesses. The general economic prosperity of the postwar years. The explosion of modernity for normal people – kitchen appliances, automobiles, television, McDonald’s, and Barbie. Finally, of course, there’s that legendary “cultural homogeneity” of the 1950s – a collective sense of shared purpose lingering from WWII, now redirected into the brave struggle against alternative economic systems and political structures. There’s great comfort in sameness, particularly when accompanied by common enemies and a newfound prosperity for those enemies to threaten.

In reality, the 1950s weren’t quite as universally unified or prosperous as they appeared. Still, it was close enough to give the 1960s something to challenge – a lifestyle and presumed set of values for the youth of the era to reject. (It’s difficult to rebel against the mainstream if there’s no mainstream.) If nothing else, the 1950s made the 1960s possible. The decade became the “ordinary world” for a whole new hero’s journey.

So… what were the boring parts we should make sure we don’t overlook?

Levittown and the Growth of the Suburbs

All those folks coming back from the war needed somewhere to live. Plus, there was that “Baby Boom” thing which somehow started increasing the population – dramatically. The name you should most remember in connection with all of this is William J. Levitt.

Levitt built entire neighborhoods of affordable, but decent, family homes. The most notable was his pilot project in Long Island, New York – Levittown. Disposable income was up, and while the 30-year mortgage so familiar today wasn’t yet standard, it was becoming increasingly popular. The federal government played with ways to keep interest rates low and gave homeowners a big ol’ tax deduction as well. (Remember the part above about using money to promote government-approved lifestyles?) It worked. Levitt sold nearly 17,000 homes in Long Island alone before moving into other markets. Needless to say, other developers quickly followed suit.

The ready availability of automobiles and the growth of highways made travel to and from work more convenient, even at a distance – and just look at all those freshly-mowed lawns… looking exactly the same! These mass-produced suburban homes weren’t always easy to tell apart. It became easy comedy to portray a husband coming home from work and entering the wrong home without ever noticing the difference. But this was the 50s – being the same as everyone else wasn’t exactly a downside.

On the other hand, that homogeneity didn’t end with the shingle choices on your Cape Cod. Levitt’s suburbs, like many others, only sold to white families. This wasn’t something subtle or implied based on a close reading of the historical data; it was established policy. Part of the appeal of the suburbs was getting away from crowded cities and into affordable convenience, but “white flight” was quite intentional as well. White neighborhoods meant your kids could go to all-white schools and you could attend all-white churches and shop at all-white stores, etc. It may seem biased or hurtful to portray racism as planned, systematic, and intentional across the board and by everyone involved; it’s just that it was planned, systematic, and intentional across the board by everyone involved.

Other than that, though, the suburbs were (and are) swell.

Prosperity Doctrines

The federal government had poured major stimulation into the economy during the war, and they were in no hurry to dial it back just because the bad guys had finally surrendered. Tax dollars both collected and anticipated were funneled into education, social programs, highways and other infrastructure, the aforementioned G.I. Bill, mortgage protection for all those new suburban homeowners, and anything else Congress could think of. While federal spending in the 1950s may have been humble by the standards of subsequent decades, the idea that it was a time of pure self-sufficiency or any version of laissez-faire economics is just silly. That would be like suggesting that homesteaders and railroads after the Civil War forged west without constant, massive government support and encouragement.

Nothing against the “invisible hand,” but it’s terrible at land grants, killing Indians, or promoting interstate travel.

In the 1950s, at least, all that government stimulation turned out to be quite effective. Americans were able to whip themselves into a consumerist frenzy, purchasing homes, cars, appliances, entertainment, and anything else they could think of. All that buying and wanting meant higher demand for pretty much everything, which meant good wages and low unemployment while somehow keeping inflation low. It was truly a marvelous time to be alive.

And white.

NEXT TIME: The 1950s (Part Two) – “It’s Moving Day!”

Many history aficionados get a bit touchy when “outsiders” label something from history “boring.” Like, anything. There’s so much we find fascinating or important or connected or just… weird that it’s easy to take it a bit personally when someone labels our interests “lame” (even when they soften such declarations with more moderate language).

Many history aficionados get a bit touchy when “outsiders” label something from history “boring.” Like, anything. There’s so much we find fascinating or important or connected or just… weird that it’s easy to take it a bit personally when someone labels our interests “lame” (even when they soften such declarations with more moderate language).