Should I Pray or Should I Go?

Three Big Things:

1. McCollum v. Board of Education was the first Supreme Court case to test the idea of “released time” during the school day for religious instruction by outside groups or religious leaders.

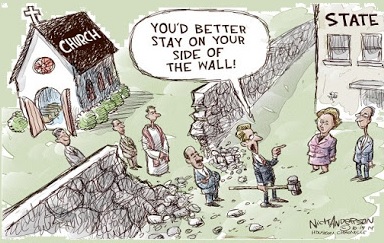

2. The Court’s four different written opinions demonstrate the complexity of applying absolutist rhetoric (“wall of separation”) to specific circumstances without trampling on the rights of local decision-makers.

3. The issues debated in McCollum reappeared in various iterations long after this particular decision and still come up in only slightly modified forms today.

Background

The Board of Education in Champaign, Illinois, allowed a local religious organization consisting of clergy and other volunteers to come into their public schools and teach religion classes during the school day. The organization, calling itself the Champaign Council on Religious Education, offered Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish options. The classes were “voluntary,” and any expenses were paid for by the Council, not the school district or parents.

The Board of Education in Champaign, Illinois, allowed a local religious organization consisting of clergy and other volunteers to come into their public schools and teach religion classes during the school day. The organization, calling itself the Champaign Council on Religious Education, offered Protestant, Catholic, or Jewish options. The classes were “voluntary,” and any expenses were paid for by the Council, not the school district or parents.

This wasn’t unique in the world of local public schools. It even had a name: “released time.” The implication was that students were temporarily “released” from school to attend “voluntary” religious classes. In practice, they had two choices – attend the religious classes, or go to whatever room or part of the school was designated for non-participants.

Vashti McCollum, an atheist with a cool name, objected to this system on several bases. Primarily, she argued, this use of public school facilities during the school day amounted to “Establishment,” thus violating the very first clause of the First Amendment. In practice, she said, students like her eight-year old son, James, faced substantial pressure from teachers and administration to attend. He was eventually forced to sit alone in the hallway while other students were being indoctrinated and endured mockery and ostracism from his peers with the tacit sanction of his teachers and other school staff. Furthermore, McCollum claimed, the power of the Council and local School Superintendent to pick and choose which religious leaders were included amounted to government censorship of some religious views in favor of others.

McCollum’s case reached the Supreme Court in 1947, the same year Everson v. Board of Education was decided. In Everson, the Court determined that state assistance to parents whose children rode public busses to school was fine, even though that assistance included families utilizing parochial schools. Everson was the first case of its kind to reach the Court and involved difficult questions about what the “wall of separation” meant in practice when applied to state and local government via the 14th Amendment. Plus, it hadn’t been decided at the time McCollum first began pursuing her case in the courts. It’s unlikely she or anyone else involved had even heard of it yet.

McCollum’s case reached the Supreme Court in 1947, the same year Everson v. Board of Education was decided. In Everson, the Court determined that state assistance to parents whose children rode public busses to school was fine, even though that assistance included families utilizing parochial schools. Everson was the first case of its kind to reach the Court and involved difficult questions about what the “wall of separation” meant in practice when applied to state and local government via the 14th Amendment. Plus, it hadn’t been decided at the time McCollum first began pursuing her case in the courts. It’s unlikely she or anyone else involved had even heard of it yet.

In other words, McCollum was stepping out with absolutely no reason to think she had a chance of winning and no real precedent on which to build her case. Her demands in the name of “separation of church and state,” which initially went well-beyond the “released time” issue, were inflammatory and unpopular. At the same time, she was seeking no damages and wasn’t insisting that anyone be fired or go to jail. What she asked of the courts was a writ of mandamus –an order from the bench to government officials to fulfill their duties properly and fix a mistake they were making, whether as an abuse of power or simply because they didn’t know any better. (The reason “writ of mandamus” sounds like something from Harry Potter is because the Latin root hints at its English offspring in words like “mandatory” or “command.”)

The McCollum family endured the usual pushback whenever community religious values were challenged – she was fired from her job for vaguely-defined reasons, they were physically threatened and verbally harassed, and their home periodically pelted with rocks and garbage. The family pet – a cat, in this case – was also killed in retaliation for her efforts.

At least those “released time” classes were doing a great job inculcating the values of their approved faiths.

When McCollum’s case reached the Supreme Court, a supportive amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief was filed by none other than the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. This group was in some ways the intellectual and spiritual descendants of those whacky Danbury Baptists who a century-and-a-half before had written to President Thomas Jefferson about the need for protection from the State. Jefferson’s response coined the phrase “a wall of separation,” which quickly became canon in interpreting the two church-state clauses of the First Amendment.

When McCollum’s case reached the Supreme Court, a supportive amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief was filed by none other than the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty. This group was in some ways the intellectual and spiritual descendants of those whacky Danbury Baptists who a century-and-a-half before had written to President Thomas Jefferson about the need for protection from the State. Jefferson’s response coined the phrase “a wall of separation,” which quickly became canon in interpreting the two church-state clauses of the First Amendment.

So that was nice.

The Decision(s)

The Court struck down the “released time” program and any similar programs in which schools set aside class time for religious instruction. Although the classes were technically voluntary and led by a mix of Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish clergy and other volunteers, the use of school facilities during school hours violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment as applied to the states by the Fourteenth.

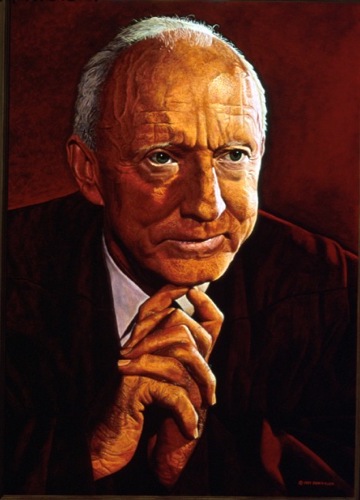

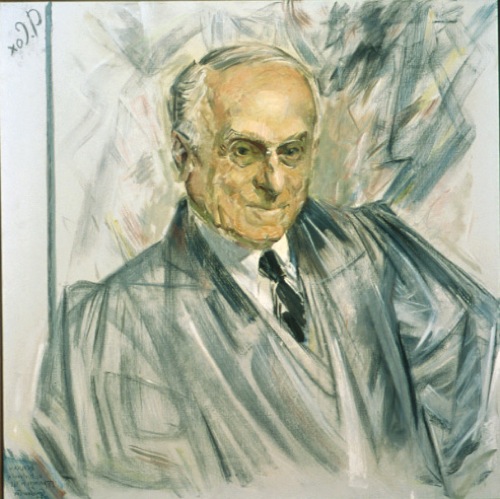

The case prompted no fewer than four distinct written opinions – the Majority Opinion, penned by Justice Hugo L. Black, two separate concurring opinions, written by Justice Felix Frankfurter (joined by two other justices) and Justice Robert J. Jackson respectively, and a dissent from Justice Stanley F. Reed. The variety of opinions expressed, even among those supporting the decision, offer rich insight into the different facets of this and subsequent related cases. The issues with which they wrestle will become familiar and appear in various forms in dozens of subsequent church-school cases.

The Majority Opinion

The Majority Opinion

Justice Hugo Black, writing for the majority, focused on the core issue of “released time” as a violation of the Establishment Clause:

The council employed the religious teachers at no expense to the school authorities, but the instructors were subject to the approval and supervision of the superintendent of schools… Classes were conducted in the regular classrooms of the school building. Students who did not choose to take the religious instruction were not released from public school duties; they were required to leave their classrooms and go to some other place in the school building for pursuit of their secular studies. On the other hand, students who were released from secular study for the religious instructions were required to be present at the religious classes. Reports of their presence or absence were to be made to their secular teachers.

The foregoing facts, without reference to others that appear in the record, show the use of tax supported property for religious instruction and the close cooperation between the school authorities and the religious council in promoting religious education… This is beyond all question a utilization of the tax-established and tax-supported public school system to aid religious groups to spread their faith…

He cited Everson by way of support, then added what would become something of a requisite disclaimer in subsequent church-school separation cases:

To hold that a state cannot, consistently with the First and Fourteenth Amendments, utilize its public school system to aid any or all religious faiths or sects in the dissemination of their doctrines and ideals does not, as counsel urge, manifest a governmental hostility to religion or religious teachings…

{T}he First Amendment rests upon the premise that both religion and government can best work to achieve their lofty aims if each is left free from the other within its respective sphere. Or, as we said in the Everson case, the First Amendment has erected a wall between Church and State which must be kept high and impregnable.

Frankfurter’s Concurrence

Frankfurter’s Concurrence

Justice Felix Frankfurter’s tone as he introduced his concurring thoughts could be perceived as a tad, well… snippy. If one weren’t paying attention, it would be easy to assume he was setting up a scathing dissent rather than a supportive addendum:

We are all agreed that the First and the Fourteenth Amendments have a secular reach far more penetrating in the conduct of Government than merely to forbid an “established church.” But agreement, in the abstract, that the First Amendment was designed to erect a “wall of separation between church and State” does not preclude a clash of views as to what the wall separates.

Involved is not only the Constitutional principle, but the implications of judicial review in its enforcement. Accommodation of legislative freedom and Constitutional limitations upon that freedom cannot be achieved by a mere phrase. We cannot illuminatingly apply the “wall of separation” metaphor until we have considered the relevant history of religious education in America, the place of the “released time” movement in that history, and its precise manifestation in the case before us.

Justice Frankfurter went on to anchor his concurring opinion in just such an extended historical analysis and application. He even quoted President Ulysses S. Grant. How often does THAT happen?

His primary argument was that this was not a new issue; the idea that public education should remain unencumbered with shifting local religious allegiances was not part of some radical new judicial activism. “Released time” was from the beginning largely an excuse to leverage the power of the state to compel public school attendance into an opportunity for indoctrinating young people who simply weren’t interested enough to listen otherwise.

Jackson’s Concurrence

Jackson’s Concurrence

Justice Robert H. Jackson, too, offered a supporting opinion which somehow didn’t sound entirely supportive. He agreed with the Court’s decision except for a few minor things, such as his uncertainty they’d established their requisite jurisdiction over the case to begin with. Jackson simply couldn’t bring himself to embrace the suggestion that the First Amendment was intended to provide the sort of relief sought by the McCollums:

When a person is required to submit to some religious rite or instruction or is deprived or threatened with deprivation of his freedom for resisting such unconstitutional requirement, {this Court} may then set him free or enjoin his prosecution. Typical of such cases was West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943). There, penalties were threatened against both parent and child for refusal of the latter to perform a compulsory ritual which offended his convictions…

But here, complainant’s son may join religious classes if he chooses and if his parents so request, or he may stay out of them. The complaint is that, when others join and he does not, it sets him apart as a dissenter, which is humiliating. Even admitting this to be true, it may be doubted whether the Constitution, which, of course, protects the right to dissent, can be construed also to protect one from the embarrassment that always attends nonconformity, whether in religion, politics, behavior or dress…

He went on to express concern that the Court did not specifically reject the wide variety of other complaints and demands brought by McCollum as part of her case. Even granting that the “released time” thing is a no-no, he didn’t like the implication that she or anyone else with their own list of religious slights or other offenses taken might conceivably cite the case by way of demanding judicial protection from pretty much anything that hurt their little feelings or offended their bizarre worldviews.

He put it a bit more jurisprudentially than that, but not by much.

Reed’s Dissent

Reed’s Dissent

Justice Stanley F. Reed, the sole dissenter in the case, had a fairly straightforward explanation of his primary objection to the Court’s ruling:

I find it difficult to extract from the opinions any conclusion as to what it is in the Champaign plan that is unconstitutional. Is it the use of school buildings for religious instruction; the release of pupils by the schools for religious instruction during school hours; the so-called assistance by teachers in handing out the request cards to pupils, in keeping lists of them for release and records of their attendance; or the action of the principals in arranging an opportunity for the classes and the appearance of the Council’s instructors?

None of the reversing opinions say whether the purpose of the Champaign plan for religious instruction during school hours is unconstitutional, or whether it is some ingredient used in or omitted from the formula that makes the plan unconstitutional.

In other words, he found the majority’s explanation of why “released time” programs were unconstitutional unconvincing primarily because the majority hadn’t explained what made them constitutional.

Whether his criticism was justified in this particular case or not, the principle he evoked is sound. Clarity as to the Court’s reasoning in any decision is essential if those impacted are to have any idea what is or is not acceptable going forward. Lower courts are expected to look to the Supreme Court for guidance in deciding related cases in their states or federal districts – something difficult to do if the explanation really were, in essence, “it just feels unconstitutional.”

Reed echoed Justice Frankfurter in his concern that the Court may have been leaning too heavily on a catchy phrase and not heavily enough on the history and context behind it:

{T}he “wall of separation between church and State” that Mr. Jefferson built at the University which he founded did not exclude religious education from that school. The difference between the generality of his statements on the separation of church and state and the specificity of his conclusions on education are considerable. A rule of law should not be drawn from a figure of speech.

Like Justice Jackson, Justice Reed was not persuaded that a child’s humiliation, even when school officials were culpable, was sufficient to trigger constitutional review:

It seems obvious that the action of the School Board in permitting religious education in certain grades of the schools by all faiths did not prohibit the free exercise of religion {by students of other faiths or beliefs}. Even assuming that certain children who did not elect to take instruction are embarrassed to remain outside of the classes, one can hardly speak of that embarrassment as a prohibition against the free exercise of religion.

Reed’s dissent concludes with an argument which would resurface in various forms almost every time public schools and proselytization had a spat in following decades:

The prohibition of enactments respecting the establishment of religion do not bar every friendly gesture between church and state. It is not an absolute prohibition against every conceivable situation where the two may work together, any more than the other provisions of the First Amendment — free speech, free press — are absolutes. If abuses occur, such as the use of the instruction hour for sectarian purposes, I have no doubt… that Illinois will promptly correct them…

This Court cannot be too cautious in upsetting practices embedded in our society by many years of experience. A state is entitled to have great leeway in its legislation when dealing with the important social problems of its population… Devotion to the great principle of religious liberty should not lead us into a rigid interpretation of the constitutional guarantee that conflicts with accepted habits of our people.

Aftermath

Four short years later, the Court would hear Zorach v. Clauson (1952), a New York case quite similar to McCollum with only one notable difference – students who wished to participate in religious instruction during the school day were “released” to leave school grounds and report to religious training elsewhere. The Court determined in a 6 – 3 decision as perfectly constitutional. The Majority Opinion, written by Justice William O. Douglas (who’d sided with the majority in McCollum), strongly echoed Justice Reed’s dissent from four years before.

Clearly, the Court was still working out the details of this “wall of separation.”

RELATED POST: “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation

RELATED POST: The Jehovah’s Witnesses Flag Cases (Part One)

RELATED POST: The Jehovah’s Witnesses Flag Cases (Part Two)

The Majority Opinion

The Majority Opinion Frankfurter’s Concurrence

Frankfurter’s Concurrence Jackson’s Concurrence

Jackson’s Concurrence Reed’s Dissent

Reed’s Dissent I’ve started putting together information and drafts for something which may or may not be titled “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation (Public School Edition). Call me wacky, but I find this stuff fascinating.

I’ve started putting together information and drafts for something which may or may not be titled “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation (Public School Edition). Call me wacky, but I find this stuff fascinating. After the Supreme Court’s decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), harassment and violence towards Jehovah’s Witnesses surged dramatically across the United States. Many felt validated and encouraged by the Court’s decision, which in their mind had essentially prioritized loyalty and being a good American over freedom of religion, speech, or association. It didn’t help that the U.S. entered World War II shortly thereafter, making patriotism and loyalty towards one’s nation and the flag representing it even more essential in the minds of many and any deviance not merely suspect, but dangerous.

After the Supreme Court’s decision in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), harassment and violence towards Jehovah’s Witnesses surged dramatically across the United States. Many felt validated and encouraged by the Court’s decision, which in their mind had essentially prioritized loyalty and being a good American over freedom of religion, speech, or association. It didn’t help that the U.S. entered World War II shortly thereafter, making patriotism and loyalty towards one’s nation and the flag representing it even more essential in the minds of many and any deviance not merely suspect, but dangerous. Perhaps not surprisingly, persecution only strengthened the resolve of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their kids still to have other gods before the Big One. It was a mere three years before almost the exact same case as Gobitis came before the High Court once again. This time, the results would be a tiny bit different.

Perhaps not surprisingly, persecution only strengthened the resolve of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Their kids still to have other gods before the Big One. It was a mere three years before almost the exact same case as Gobitis came before the High Court once again. This time, the results would be a tiny bit different. West Virginia and other states did allow some modification of the stiff-arm salute now associated with the Nazi Party. (Presumably, it was OK to behave like fascists as long as one used a slightly different arm motion while so doing.) They also tweaked the rules concerning expulsion. Children not saluting the flag and saying the Pledge would be sent home, after which parents would be prosecuted for not having them in school.

West Virginia and other states did allow some modification of the stiff-arm salute now associated with the Nazi Party. (Presumably, it was OK to behave like fascists as long as one used a slightly different arm motion while so doing.) They also tweaked the rules concerning expulsion. Children not saluting the flag and saying the Pledge would be sent home, after which parents would be prosecuted for not having them in school. In a rather bold move, the three-judge court not only decided in favor of the Barnettes, but made no effort to justify their decision by pretending this case was in some way different than its predecessor. Instead, they simply explained their reasoning based on developments since Gobitis, along with their own interpretation of the law and the Bill of Rights. Taken together, it’s a written opinion as eloquent as anything coming from the Supremes in those days:

In a rather bold move, the three-judge court not only decided in favor of the Barnettes, but made no effort to justify their decision by pretending this case was in some way different than its predecessor. Instead, they simply explained their reasoning based on developments since Gobitis, along with their own interpretation of the law and the Bill of Rights. Taken together, it’s a written opinion as eloquent as anything coming from the Supremes in those days: The State appealed the case up the ladder (hence the reversal in the order of the names) and the Supreme Court was given an opportunity to try again. This time, they ruled 6 – 3 in favor of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The majority focused less on religious freedom for Jehovah’s Witnesses and more on freedom of speech (or lack thereof) in general. It’s not just that children of certain faiths should be free to respectfully abstain from public recitations of mandatory patriotism, they argued – it was bigger than that. There are certain core liberties which should be protected for everyone, regardless of the specific belief system or point of view involved:

The State appealed the case up the ladder (hence the reversal in the order of the names) and the Supreme Court was given an opportunity to try again. This time, they ruled 6 – 3 in favor of the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The majority focused less on religious freedom for Jehovah’s Witnesses and more on freedom of speech (or lack thereof) in general. It’s not just that children of certain faiths should be free to respectfully abstain from public recitations of mandatory patriotism, they argued – it was bigger than that. There are certain core liberties which should be protected for everyone, regardless of the specific belief system or point of view involved: Barnette was a turning point for jurisprudence involving the freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Initially, the first ten Amendments were added to the new Constitution as limits on what the federal government could do or demand of individuals. While state constitutions might offer similar protections for speech, religion, etc., there was no national standard for such things until the first half of the 20th century, when the Court began utilizing the 14th Amendment (ratified just after the Civil War, in 1868) to apply the protections and ideals of the Bill of Rights to the relationship between citizens and state or local government as well.

Barnette was a turning point for jurisprudence involving the freedoms enshrined in the Bill of Rights. Initially, the first ten Amendments were added to the new Constitution as limits on what the federal government could do or demand of individuals. While state constitutions might offer similar protections for speech, religion, etc., there was no national standard for such things until the first half of the 20th century, when the Court began utilizing the 14th Amendment (ratified just after the Civil War, in 1868) to apply the protections and ideals of the Bill of Rights to the relationship between citizens and state or local government as well. The basic principle still holds – there are laws and expectations ever citizen must heed, regardless of belief system or personal creed. After Barnette, though, sincerely held religious convictions gained substantial ground in terms of what they could or couldn’t be used to justify, both in the world of public education and beyond. Also magnified was the idea that fundamental freedoms like those guaranteed in the Bill of Rights shouldn’t have to wait on legislatures or the next election to find protection – an approach which will be applied to full effect by the Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s.

The basic principle still holds – there are laws and expectations ever citizen must heed, regardless of belief system or personal creed. After Barnette, though, sincerely held religious convictions gained substantial ground in terms of what they could or couldn’t be used to justify, both in the world of public education and beyond. Also magnified was the idea that fundamental freedoms like those guaranteed in the Bill of Rights shouldn’t have to wait on legislatures or the next election to find protection – an approach which will be applied to full effect by the Warren Court of the 1950s and 1960s. Several years ago, my wife and I moved to northern Indiana from Oklahoma and I started a job at a new school. Day One, first hour, I was about 30 seconds into introducing our opening activity when I was interrupted by announcements via school intercom. “Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance…”

Several years ago, my wife and I moved to northern Indiana from Oklahoma and I started a job at a new school. Day One, first hour, I was about 30 seconds into introducing our opening activity when I was interrupted by announcements via school intercom. “Please stand for the Pledge of Allegiance…” I recently finished

I recently finished  In the waning years of the Great Depression, as Europe stumbled towards war, patriotism in the United States became mandatory in all but name. Many states passed laws requiring all public school students to salute the American Flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance each day, apparently assuming that nothing promotes heartfelt commitment like mandatory obeisance. If you’ve seen pictures from the era, you may notice that the standard salute looked different than it does today. Typically, it involved the right arm extended forward and upwards at a slight degree towards the flag as participants chanted in unison their devotion to the collective.

In the waning years of the Great Depression, as Europe stumbled towards war, patriotism in the United States became mandatory in all but name. Many states passed laws requiring all public school students to salute the American Flag and say the Pledge of Allegiance each day, apparently assuming that nothing promotes heartfelt commitment like mandatory obeisance. If you’ve seen pictures from the era, you may notice that the standard salute looked different than it does today. Typically, it involved the right arm extended forward and upwards at a slight degree towards the flag as participants chanted in unison their devotion to the collective. We like to imagine the Supreme Court as remaining safely beyond the pale of popular opinion or social forces, but they are at times quite human and may even read the news from time to time. The makeup of the Court evolves as well, and shortly after the Gobitis decision, it changed rather dramatically. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes retired, as did Justice McReynolds. Justice Stone, author of the sole dissent in Gobitis, was promoted to Chief Justice, and Justices Robert Jackson and Wiley Rutledge joined the Court.

We like to imagine the Supreme Court as remaining safely beyond the pale of popular opinion or social forces, but they are at times quite human and may even read the news from time to time. The makeup of the Court evolves as well, and shortly after the Gobitis decision, it changed rather dramatically. Chief Justice Charles E. Hughes retired, as did Justice McReynolds. Justice Stone, author of the sole dissent in Gobitis, was promoted to Chief Justice, and Justices Robert Jackson and Wiley Rutledge joined the Court. Background

Background