Excerpts from the Federalist Papers #78 (Alexander Hamilton)

The Federalist Papers were a series of 85 essays written by John Jay (5), James Madison (29), and Alexander Hamilton (51) to explain and defend the new Constitution in hopes of securing unanimous ratification. While not part of the document, they are generally considered one of the most reliable sources of the Framers’ intentions. Hamilton was the original “Federalist” in terms of his commitment to a strong central government and an expansive reading of the Constitution and the powers it grants to the various branches. Unlike Thomas Jefferson, who was primarily concerned with protecting the liberties of individuals, Hamilton’s focus was on strengthening the powers of the federal government sufficiently to ensure its long-term success. And yet, here in Essay #78, he argues that lifetime appointments are essential in the judicial branch in order to assure attention to precedent and consistent protection of individual liberties from legislative abuse.

WE PROCEED now to an examination of the judiciary department of the proposed government…

{T}he judiciary is beyond comparison the weakest of the three departments of power… {T}hough individual oppression may now and then proceed from the courts of justice, the general liberty of the people can never be endangered from that quarter; I mean so long as the judiciary remains truly distinct from both the legislature and the Executive. For I agree, that “there is no liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers.” … {Since} liberty can have nothing to fear from the judiciary alone, but would have everything to fear from its union with either of the other departments… {and since the judicial branch is the weakest of the three,} nothing can contribute so much to its firmness and independence as permanency in office{. T}his quality may therefore be justly regarded as an indispensable ingredient in its constitution, and, in a great measure, as the citadel of the public justice and the public security.

We might debate whether or not Hamilton was correct to consider the judicial branch the “weakest” of the three, but what’s important here is the idea that the lifetime tenure of justices was intended to provide consistency in the nation’s highest court. Notice also his assumption that one of the primary purposes of the Court is to protect the “general liberty of the people” and act as the “citadel of the public justice and the public security.” While Hamilton was speaking primarily of national government (it would almost a century before constitutional protections were automatically assumed to apply at the state and local level via the Fourteenth Amendment), this understanding of the judicial branch is antithetical to the idea that “faithfulness” to the Constitution requires stripping away established protections in order to better facilitate state-level abuse of personal liberties.

The complete independence of the courts of justice is peculiarly essential in a limited Constitution. By a limited Constitution, I understand one which contains certain specified exceptions to the legislative authority… Limitations of this kind can be preserved in practice no other way than through the medium of courts of justice, whose duty it must be to declare all acts contrary to the manifest tenor of the Constitution void. Without this, all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing…

There is no position which depends on clearer principles, than that every act of a delegated authority, contrary to the tenor of the commission under which it is exercised, is void. No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the Constitution, can be valid. To deny this, would be to affirm, that the deputy is greater than his principal; that the servant is above his master; that the representatives of the people are superior to the people themselves; that men acting by virtue of powers, may do not only what their powers do not authorize, but what they forbid…

The power of “judicial review” was formally claimed by the Supreme Court in its landmark decision in Marbury v. Madison (1803). The concept, however, was established long before then. One of the primary reasons Jefferson and Madison had so much trouble garnering support for their Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions (1798-1799) which promoted state “nullification” of the Alien and Sedition Acts was that even state legislatures who didn’t love these statutes deferred to the appropriate branch of government for dealing with such things. In this essay, Hamilton is not suggesting “judicial review” as a potential power of the Supreme Court; he’s explaining and justifying it as something clearly granted under the new Constitution… even if it wasn’t spelled out in exactly those words.

If it be said that the legislative body are themselves the constitutional judges of their own powers, and that the construction they put upon them is conclusive upon the other departments, it may be answered, that this cannot be the natural presumption, where it is not to be collected from any particular provisions in the Constitution. It is not otherwise to be supposed, that the Constitution could intend to enable the representatives of the people to substitute their WILL to that of their constituents. It is far more rational to suppose, that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority.

Until Justice Clarence Thomas and his ilk manage to effectively neuter the Fourteenth Amendment, it’s reasonable to apply this philosophy to state governments as well as the national Congress. The original purpose of the Fourteenth Amendment, after all, was to decry “states’ rights” when they violated more fundamental (and more important) natural rights.

The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.

Nor does this conclusion by any means suppose a superiority of the judicial to the legislative power. It only supposes that the power of the people is superior to both; and that where the will of the legislature, declared in its statutes, stands in opposition to that of the people, declared in the Constitution, the judges ought to be governed by the latter rather than the former. They ought to regulate their decisions by the fundamental laws, rather than by those which are not fundamental.

President Andrew Jackson saw himself as defending the “common man” from the corrupted powers of their elected legislators. According to Hamilton, however, the primary defense of the people from legislative bodies is the courts. That’s not “judicial activism,” according to one of the strongest proponents of powerful central government in our history – it’s one of the judicial system’s primary functions.

This exercise of judicial discretion, in determining between two contradictory laws, is exemplified in a familiar instance. It not uncommonly happens, that there are two statutes existing at one time, clashing in whole or in part with each other, and neither of them containing any repealing clause or expression. In such a case, it is the province of the courts to liquidate and fix their meaning and operation. So far as they can, by any fair construction, be reconciled to each other, reason and law conspire to dictate that this should be done; where this is impracticable, it becomes a matter of necessity to give effect to one, in exclusion of the other. The rule which has obtained in the courts for determining their relative validity is, that the last in order of time shall be preferred to the first. But this is a mere rule of construction, not derived from any positive law, but from the nature and reason of the thing. It is a rule not enjoined upon the courts by legislative provision, but adopted by themselves, as consonant to truth and propriety, for the direction of their conduct as interpreters of the law. They thought it reasonable, that between the interfering acts of an EQUAL authority, that which was the last indication of its will should have the preference…

What Hamilton is essentially talking about here is stare decisis – the importance of maintaining judicial precedents. When laws (or, say… clauses in the First Amendment) clash or pull against one another, it’s the job of the Supreme Court to figure out the best understanding of those laws and establish this as the correct meaning.

This independence of the judges is equally requisite to guard the Constitution and the rights of individuals from the effects of those ill humors, which the arts of designing men, or the influence of particular conjunctures, sometimes disseminate among the people themselves, and which, though they speedily give place to better information, and more deliberate reflection, have a tendency, in the meantime, to occasion dangerous innovations in the government, and serious oppressions of the minor party in the community.

Hamilton may not have been quite the progressive crusader suggested by his musical, but he’s at least pro-Warren Court here.

It’s worth repeating – a primary duty of the courts is to protect individual liberties (in this case, minority rights specifically) from legislative abuses. That’s not “exceeding” their constitutional role, at least according to the guys who wrote the damn thing.

Surely you can’t get much more “originalist” than that.

Though I trust the friends of the proposed Constitution will never concur with its enemies, in questioning that fundamental principle of republican government, which admits the right of the people to alter or abolish the established Constitution, whenever they find it inconsistent with their happiness, yet it is not to be inferred from this principle, that the representatives of the people, whenever a momentary inclination happens to lay hold of a majority of their constituents, incompatible with the provisions in the existing Constitution, would, on that account, be justifiable in a violation of those provisions; or that the courts would be under a greater obligation to connive at infractions in this shape, than when they had proceeded wholly from the cabals of the representative body. Until the people have, by some solemn and authoritative act, annulled or changed the established form, it is binding upon themselves collectively, as well as individually; and no presumption, or even knowledge, of their sentiments, can warrant their representatives in a departure from it, prior to such an act. But it is easy to see, that it would require an uncommon portion of fortitude in the judges to do their duty as faithful guardians of the Constitution, where legislative invasions of it had been instigated by the major voice of the community.

It’s nice of him to go ahead and validate the January 6th hearings while he’s at it. Alexander “Nostradamus” Hamilton, at your service.

Hamilton continues making his point that lifetime tenure is essential for the judiciary to effectively protect individual liberty against potential abuses by the other two branches (but mostly the legislative). Apparently he doesn’t consider elected representatives to always be the best judges of what the Constitution does and doesn’t protect. Huh.

It turns out there’s even a more important reason for those lifetime appointments – they help protect stare decisis by making justices less likely to overturn established precedents in service of their own ideological whims. At least, that was the idea.

There is yet a further and a weightier reason for the permanency of the judicial offices, which is deducible from the nature of the qualifications they require. It has been frequently remarked, with great propriety, that a voluminous code of laws is one of the inconveniences necessarily connected with the advantages of a free government. To avoid an arbitrary discretion in the courts, it is indispensable that they should be bound down by strict rules and precedents, which serve to define and point out their duty in every particular case that comes before them…

Precedent matters. It’s not inviolable, but it should carry greater weight than “yeah, but we don’t like how the last fifty years or so have gone.” It should certainly trump “you don’t know how long the Federalist Society and rich white evangelicals have been working to reverse course on this stuff!”

Hamilton was concerned that excessive turnover on the bench would produce justices insufficiently schooled in established jurisprudence. He did not account for the possibility that they’d know damn well what’s been said and done before but simply pick and choose selected bits to justify their predetermined outcomes while ignoring context and inevitable impact.

{T}here can be but few men in the society who will have sufficient skill in the laws to qualify them for the stations of judges. And… the number must be still smaller of those who unite the requisite integrity with the requisite knowledge.

You said it, Alexander.

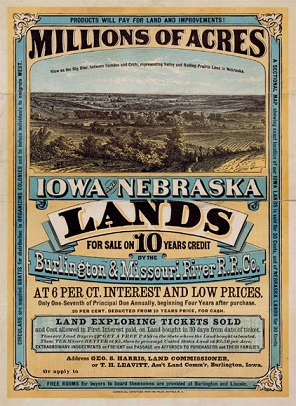

Land was a big deal when our little experiment in democracy began. Why?

Land was a big deal when our little experiment in democracy began. Why?  So, in order to assure that everyone’s political voice is more or less equal, we’re going to have to deny a political voice to some – to those without the ability to provide for themselves. Otherwise, the entire representative system may be undermined through the ability of the wealthy to manipulate the indigent.

So, in order to assure that everyone’s political voice is more or less equal, we’re going to have to deny a political voice to some – to those without the ability to provide for themselves. Otherwise, the entire representative system may be undermined through the ability of the wealthy to manipulate the indigent. No help here from the ‘Father of the Constitution’. Apparently handing power over to men without land leads to either a tyranny of the masses (mob democracy) or a system in which the ignorant are led about by the manipulations of the wealthy and power-hungry.

No help here from the ‘Father of the Constitution’. Apparently handing power over to men without land leads to either a tyranny of the masses (mob democracy) or a system in which the ignorant are led about by the manipulations of the wealthy and power-hungry. Keep in mind this was a new country – a baby nation. The Declaration was as much a Birth Certificate as a break-up letter, and our forebears were trying something entirely new. They were idealists, sure – but they were also educated, and realists, and had some idea how people tend to people-ize.

Keep in mind this was a new country – a baby nation. The Declaration was as much a Birth Certificate as a break-up letter, and our forebears were trying something entirely new. They were idealists, sure – but they were also educated, and realists, and had some idea how people tend to people-ize. Adams probably talked too much, but I do love how he steps his audience through his reasoning. It’s very Socrates, very Holmes, very Bill Nye the Government Guy. Franklin may have been the poster child of the Enlightenment in the New World, but Adams was its lesson planner and edu-blogger.

Adams probably talked too much, but I do love how he steps his audience through his reasoning. It’s very Socrates, very Holmes, very Bill Nye the Government Guy. Franklin may have been the poster child of the Enlightenment in the New World, but Adams was its lesson planner and edu-blogger. Power always follows Property. This I believe to be as infallible a Maxim, in Politicks, as, that Action and Re-action are equal, is in Mechanicks. Nay I believe We may advance one Step farther and affirm that the Ballance of Power in a Society, accompanies the Ballance of Property in Land.

Power always follows Property. This I believe to be as infallible a Maxim, in Politicks, as, that Action and Re-action are equal, is in Mechanicks. Nay I believe We may advance one Step farther and affirm that the Ballance of Power in a Society, accompanies the Ballance of Property in Land.