Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About… the Interstate Commerce Act & the Interstate Commerce Commission

Three Big Things:

1. After several states attempted to limit the power of railroads and grain storage facilities on behalf of farmers and other citizens, Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act (1887). This established the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) to regulate railroads, including their shipping rates and route choices.

2. The ICC was the first federal regulatory agency; it’s “success” spawned hundreds of others in subsequent decades. When you hear people complain about “big government,” these are a big part of what they mean. At the same time, they remind us that economic systems are not natural rights; they’re practical mechanisms designed to serve the largest number of people in the most efficient ways possible – at least in theory.

3. Ideally, regulatory agencies attempt to balance the good of society and the general public with the rights of companies to make reasonable profits from providing useful goods and services. They oversee “public services” – things considered essential for most citizens but which don’t easily lend themselves to a competitive marketplace due to the infrastructure required or the necessary scale of the service.

Context

The second half of the nineteenth century was one of America’s greatest (and most controversial) eras of expansion. Rugged, individualistic homesteaders navigated bureaucracy and accepted government oversight to secure their own plots of government-sponsored land in the west, where the government was hard at work clearing out the local populace on their behalf. Railroads, arguably the most poignant symbol of progress in all of Americana, were bravely, capitalistically accepting massive government land grants in exchange for laying their tracks across the Great Plains and finally connecting one coast with another. Along the way they manipulated local townships into catering to their every fiscal whim, lest they destroy them by altering course and instead bestow their blessings on communities more willing to kiss their caboose.

For railroads, more miles of track, continued national expansion, and the vast quantities of crops farmers were shipping further and further from where they were grown meant increased profits and political influence. For farmers, on the other hand, more land, technological advances, and increased production meant lower prices, endless struggles, and increased debt just to stay in the game. Eventually, traditionally individualistic farmers began forming collectives – the Grange, the Farmers’ Alliance, etc. – and pressuring their state and local governments to balance the scales a bit. They weren’t looking for handouts, just some restraints on what they saw as unchecked corporate power and greed. It wasn’t long before other segments of society began adding their voices in support.

Regulating For The Public Good

In Munn v. Illinois (1877), the Supreme Court determined that it was perfectly constitutional for a state to regulate industries within its borders, including capping the amounts grain elevators and storage warehouses were allowed to charge for their services. As the Court explained,

When one becomes a member of society, he necessarily parts with some rights or privileges which, as an individual not affected by his relations to others, he might retain. “A body politic,” as aptly defined in the preamble of the Constitution of Massachusetts, “is a social compact by which the whole people covenants with each citizen, and each citizen with the whole people, that all shall be governed by certain laws for the common good.”

This does not confer power upon the whole people to control rights which are purely and exclusively private… but it does authorize the establishment of laws requiring each citizen to so conduct himself, and so use his own property, as not unnecessarily to injure another. This is the very essence of government.

In other words, capitalism is all very fine and well, and the individual’s (or even the corporation’s) right to property and profit is important – but only because this economic approach presumably serves a larger good. The U.S. doesn’t practice a form of free market economics because it’s holy and just to do so – it’s a pragmatic decision based on the perceived shortcomings of alternative economic systems in comparison. (To paraphrase Winston Churchill, “Capitalism is the worst economic system except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”)

Munn marked as well as anything the birth of the idea that governments can and should regulate industries deemed essential to the general welfare. At the time, that primarily meant stuff related to farming and the distribution of crops, but it would eventually encompass any number of public “utilities” (electricity, water, gas, etc.) as well as some transportation systems, television and radio broadcasting, and even trash pickup.

Many would argue that as society and technology continue to evolve, the same sorts of regulation should apply to internet access, cell phone plans, and even health care and other medical services. While it’s usually pretty easy to find a new burger joint if the one you liked before starts skimping on fries or changes their menu, it’s harder to change gas companies. The local sewer service rarely competes for your business, and only a small percentage of American homeowners get to actually choose who provides their electricity – let alone at what rate. Anytime laissez-faire capitalism would result in an “essential” service being reserved for the elite few, government steps in and makes everyone play nice. Companies providing valuable services deserve to make a reasonable profit, but not at the cost of the larger social good – or so the reasoning goes.

In the late nineteenth century, however, it was primarily grain storage and railroad rates.

The Commerce Clause Wins Again

Not quite a decade after Munn, the Court revised its opinion while pretending it was simply picking up where it left off. Wabash, St. Louis and Pacific Railway Company v. Illinois (1886) clarified that while states had the right to regulate industries within their borders, that power didn’t extend beyond state lines. Just because a railroad route began in Chicago, that didn’t mean the Illinois legislature could dictate shipping rates or other policies as it choo-choo-ed through Iowa or Missouri. This was “interstate commerce” in the truest sense of the term, making it the exclusive province of Congress – whether they chose to act on it or not.

Congress finally took the hint and created the very first federal “regulatory agency” – the Interstate Commerce Commission – in 1887. The ICC was charged with overseeing railroads and shipping of all sorts, and set strict guidelines for how the railroads could do business. Rates had to be the same for short trips as for long, and for all customers, however much or little they shipped. Railroads couldn’t even offer special packages for “preferred destinations.”

The specific rules weren’t the important part, however. These were modified or eliminated as technology, transportation, and society evolved. The important thing was the idea that government could and should set limits on important industries for the good of society. In practice, this usually means federal government. It’s nearly impossible today to find a good or service functioning purely “intrastate.” States can sometimes add to regulations while the good or service is withing their purview, but not beyond.

Over the next century, hundreds of federal agencies would be created in the image of the ICC. While Congress still established guidelines and priorities, agency directors and bureaucrats were left with the detail work – writing the actual rules and at times even taking part in enforcement. When you hear people complain about the unending nightmare of red tape, small print, and regulatory burdens on pretty much everything, this is what they mean. The positive side is that the meat you bought at the store today is probably not rotten and your kids’ clothes probably won’t burst into flames anytime the sun is too bright. The negative side is that unchecked bureaucracy tends to grow like the demonic kudzu and has proven nearly impossible to restrain, let alone prune back. No one can even agree on how many federal regulatory agencies there are, let alone which ones are necessary or what at each of them is actually in charge of.

The ICC was dissolved in 1995 after most of its regulatory power had been reduced or stripped away. Its few remaining functions were transferred to yet another agency – the “Surface Transportation Board” (as opposed to all those other sorts of transportation) which operates under the “U.S. Department of Transportation.” The Secretary of Transportation, in turn, reports directly to the President.

How Do I Remember This? (And Why It Matters)

Much of American history can be viewed as an ongoing struggle between freedom and security – nationally, locally, legally, socially, and – as in this case – economically. Just like in school, too little freedom stifles innovation and productivity; too much freedom leads to chaos, abuse, and a breakdown of the system.

The Interstate Commerce Act and ICC were the federal government’s first major effort to restrict what big business could and couldn’t do in an effort to ensure the results served everyone, not just those already at the top of the economic ladder. The resulting arguments would sound surprisingly familiar nearly a century-and-a-half later. Is it better to let big business run free or rein it in from time to time? Is government better or worse than raw capitalism at meeting the needs of the people as a whole over time? Do the basic rights guaranteed to American citizens as individuals apply to corporations as well?

If the answer to any of these questions seems obvious or easy, you’re doing it wrong.

The ICC, while no longer with us, remains the granddaddy of all federal bureaucracy and regulation. From the “alphabet agencies” of the New Deal to the half-dozen different agencies which today dictate the minutia of salmon treatment, processing, costs, transportation, and preparation long before you squeeze lemon on it at your local chain restaurant – they can all be traced back to the Interstate Commerce Commission… for better or worse.

What You’re Most Likely To Be Asked

It’s unlikely you’ll be asked to recognize or analyze the language of the Interstate Commerce Act itself (it’s not that readable). Instead, make sure you understand its connection to pretty much everything else going on at the time. It’s also a nice precursor to discussing populism (the late 19th century version) or even the Progressive movements of the early 20th century. They were all about using government to balance the power of big business against the needs of the “common man.”

In APUSH, Period 6 (1865-1898) is packed with standards related to economic development and industrial growth. The rest mostly involve westward expansion and the farmers movement (“populism”). The ICC is about both, particularly in relation to one another. Knowing the basics will help you add relevant details for any prompt related to government regulation, important Supreme Court decisions of the nineteenth century, or early efforts by farmers to push back against big businesses. It should always be mentioned when speaking or writing about railroads in this period as well. It may not be the single most important thing from this half-century, but it connects to almost everything else happening at the time – and that makes it mighty useful for making yourself look knowledgeable. (KC-6.1.III, KC-6.3, KC-6.3.II, and others)

Utah’s Core Social Studies Standards pose a question many teachers love asking in some form:

How could industrial leaders be considered both “captains of industry” and “robber barons”? (U.S. II Strand I – Industrialization)

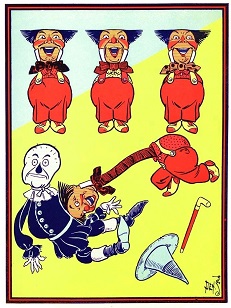

It’s a topic typically addressed while covering the Gilded Age (closer to the start of the twentieth century), but it’s a great chance to reference events associated with the creation of the ICC. Railroads were essential to American growth and progress, as were grain storage facilities, banks, and other “wicked witch” industries of the late nineteenth century. At the same time, they tended to exploit and discard anyone non-essential to their continued growth and power. It was capitalism at its most dichotomous (the whole point of the question).

If you’re not feeling that bold, chances are good you’ll be asked something along the lines of this substandard from Utah. Some variation of this is present in over half of all state social studies standards:

Students will assess how innovations in transportation, science, agriculture, manufacturing, technology, communication, and marketing transformed America in the 19th and early 20th centuries. (U.S. II Standard 1.1)

At the very least you should recognize the ICC as the first federal regulatory agency and railroads as the first federally regulated industry.

Bonus Points: How To Sound Like You Know More Than You Do

Congress’s authority to regulate interstate commerce is found in Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution. As a practical matter, this means that Congress can regulate almost anything by tying it in some way to interstate commerce – a power confirmed by the Supreme Court a half-century before in one of those “must know” cases, Gibbons v. Ogden (1824). Combined with the “Necessary and Proper Clause” (also in Article I, Section 8; confirmed by McCulloch v. Maryland, 1819), Congress and its regulatory power became virtually unchallengeable. Throw in details like what’s covered above, then thoughtfully note that this same basic tension – big government vs. small, the Hamiltonian approach vs. the Jeffersonian approach, etc. – is still a fundamental source of conflict between the two major parties today. (You’ll have literally covered the entire range of American history in a single observation.)

If your teacher seems to lean a bit conservative (they gripe about “those people” or refer to the Civil War as “the war of Northern Aggression,” etc.), you might ingratiate yourself by referring to the current web of federal regulations (which started with the ICC) as “Kafkaesque.” Kafka was a novelist who specialized in the bizarre, especially when it involved protagonists overwhelmed by systems or powers beyond their understanding or control but forced to go along with them anyway. Remember the guy who wakes up as a giant cockroach one day and we never find out why? That was his. “Kafkaesque” is a nice literary touch and should tingle their little conservative hearts without actually committing you to any particular worldview.

Above all else, avoid taking easy positions on the “good” or “bad” of railroads, regulation, farmers’ demands, or even the ICC itself. Always reference specifics while nevertheless acknowledging the inherent complexity and the valid claims of both (or all) sides – freedom, competition, and capitalism on one side and a reasonable opportunity for individuals to succeed (or at least survive) on the other. That’s what makes it interesting – the lack of easy answers.

In 1900, L. Frank Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a children’s book he wasn’t convinced would do particularly well – not compared to his fabulous Mother Goose and Father Goose collections a few years prior. Turns out it was a hit, and spawned multiple stage versions – usually musicals – and thirteen written sequels by Baum.

In 1900, L. Frank Baum published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, a children’s book he wasn’t convinced would do particularly well – not compared to his fabulous Mother Goose and Father Goose collections a few years prior. Turns out it was a hit, and spawned multiple stage versions – usually musicals – and thirteen written sequels by Baum.

The Tin Man = Northeastern Factory Workers. Having slaved away under dehumanizing conditions for so long, they’d essentially lost their souls – their hearts – the parts which make us most human. Upton Sinclair would capture this less festively a few years later in The Jungle, a book he intended to be about the factory-driven destruction of the human spirit and instead ended up being about how gross sausage is. Meat-packing was reformed; factory labor continued to kill the human spirit for another few generations.

The Tin Man = Northeastern Factory Workers. Having slaved away under dehumanizing conditions for so long, they’d essentially lost their souls – their hearts – the parts which make us most human. Upton Sinclair would capture this less festively a few years later in The Jungle, a book he intended to be about the factory-driven destruction of the human spirit and instead ended up being about how gross sausage is. Meat-packing was reformed; factory labor continued to kill the human spirit for another few generations.  The Yellow Brick Road = The Gold Standard. It’s an almost sacred path to the Emerald City, but one fraught with inconsistency and danger. There are pitfalls and surprises, and even substantial gaps prohibiting all but the most creative travelers for going forward. But, when you add…

The Yellow Brick Road = The Gold Standard. It’s an almost sacred path to the Emerald City, but one fraught with inconsistency and danger. There are pitfalls and surprises, and even substantial gaps prohibiting all but the most creative travelers for going forward. But, when you add…

On the other hand, there are plenty of events which even the most creative mind can’t reasonably tie to history or populism. The Quadlings who lack arms but fire their heads at you on long necks are a fascinating obstacle, and the fragile ‘china people’ are far more poignant once you drop the weak ‘unreconstructed South’ connection. And how many varieties of ‘the little people’ (or field mice or Winkies or…) can one book have before it no longer makes sense to label them all with the same Jacksonian value?

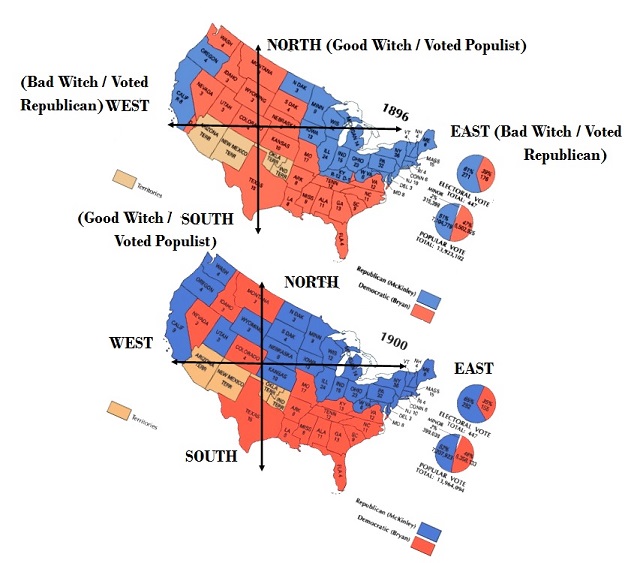

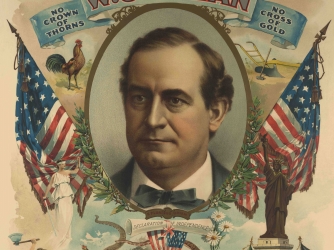

On the other hand, there are plenty of events which even the most creative mind can’t reasonably tie to history or populism. The Quadlings who lack arms but fire their heads at you on long necks are a fascinating obstacle, and the fragile ‘china people’ are far more poignant once you drop the weak ‘unreconstructed South’ connection. And how many varieties of ‘the little people’ (or field mice or Winkies or…) can one book have before it no longer makes sense to label them all with the same Jacksonian value? The Populist Party reached their zenith in the 1890’s. Although they won state and local elections here and there, before and after this decade, their only real shot at the Presidency came in the Elections of 1896 and 1900. Both times they ran William Jennings Bryan as their candidate, and both times the Democratic Party gave in and joined them in the nomination.

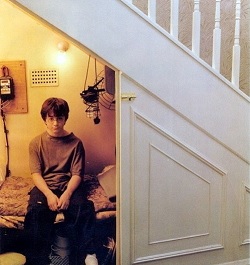

The Populist Party reached their zenith in the 1890’s. Although they won state and local elections here and there, before and after this decade, their only real shot at the Presidency came in the Elections of 1896 and 1900. Both times they ran William Jennings Bryan as their candidate, and both times the Democratic Party gave in and joined them in the nomination. I mean, Harry Potter was safe and secure at the Dursley’s under the stairs – literally and completely. No harm could come to him. As the series progressed, he grew increasingly autonomous and faced greater and greater danger. Finally, released even from the rules of Hogwarts or the direction of Dumbledore – completely and totally independent – he frickin’ DIES!

I mean, Harry Potter was safe and secure at the Dursley’s under the stairs – literally and completely. No harm could come to him. As the series progressed, he grew increasingly autonomous and faced greater and greater danger. Finally, released even from the rules of Hogwarts or the direction of Dumbledore – completely and totally independent – he frickin’ DIES! Not that most American farmers in the late 19th century were pondering such abstractions. Mostly they’d joined their voices – and their votes – to demand a few basic policy changes to compensate for what they perceived as gross imbalance in the economic order of things. They didn’t see themselves as wanting ‘help’ so much as fighting to remove cancers in the system.

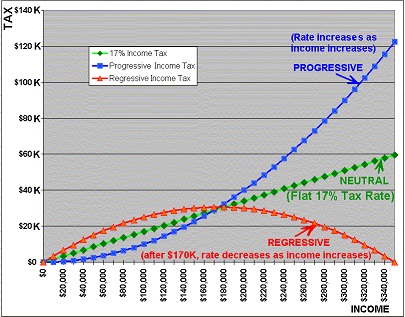

Not that most American farmers in the late 19th century were pondering such abstractions. Mostly they’d joined their voices – and their votes – to demand a few basic policy changes to compensate for what they perceived as gross imbalance in the economic order of things. They didn’t see themselves as wanting ‘help’ so much as fighting to remove cancers in the system. The Populists wanted a weighted system. If you made $10,000 this year, you pay little, or nothing. You made $50,000? Ten percent. $250,000? Twenty percent. $1,000,000? Fifty percent. Those making the most were still left with more than everyone else, and those making the least were freed from the burden of paying at all.

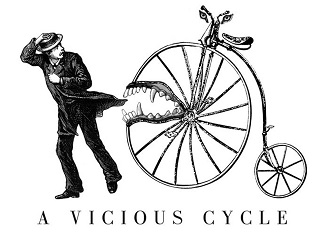

The Populists wanted a weighted system. If you made $10,000 this year, you pay little, or nothing. You made $50,000? Ten percent. $250,000? Twenty percent. $1,000,000? Fifty percent. Those making the most were still left with more than everyone else, and those making the least were freed from the burden of paying at all.  If you’re a bi… cycle, you have two wheels.

If you’re a bi… cycle, you have two wheels. Silver is valuable and not at all common, but it’s far more plentiful than its friend gold. The change would be dramatic. More money in circulation lowers the value of each dollar – counterintuitively helping those with less money and especially those in debt.

Silver is valuable and not at all common, but it’s far more plentiful than its friend gold. The change would be dramatic. More money in circulation lowers the value of each dollar – counterintuitively helping those with less money and especially those in debt. The food quickly draws attention and Max offers him a dollar for one of the slices. He accepts.

The food quickly draws attention and Max offers him a dollar for one of the slices. He accepts.  He sells most of the first box, but things quickly slow. Lowering the price to $1.00 helps a little, but it still looks like he’ll be stuck with 9 or 10 boxes of pizza with ten minutes to go. He panics and drops to 50 cents a slice… then a quarter… and manages to move enough that he’s only losing a little money for his troubles.

He sells most of the first box, but things quickly slow. Lowering the price to $1.00 helps a little, but it still looks like he’ll be stuck with 9 or 10 boxes of pizza with ten minutes to go. He panics and drops to 50 cents a slice… then a quarter… and manages to move enough that he’s only losing a little money for his troubles.

The 1890 Census would soon declare the frontier ‘closed’, to the chagrin of men like Frederick Jackson Turner who believed the westward struggle against nature and deprivation both defined and strengthened American character. Things were so desperate that white guys began looking lustfully at Oklahoma as their last best hope – the same ‘Indian Territory’ (I.T.) to whom the bulk of surviving Amerindians had been forcibly removed.

The 1890 Census would soon declare the frontier ‘closed’, to the chagrin of men like Frederick Jackson Turner who believed the westward struggle against nature and deprivation both defined and strengthened American character. Things were so desperate that white guys began looking lustfully at Oklahoma as their last best hope – the same ‘Indian Territory’ (I.T.) to whom the bulk of surviving Amerindians had been forcibly removed.  It wasn’t always a lack of production. Many farmers across the Plains were quite successful – at least in the traditional sense. They were growing and raising more good stuff than ever before! Wheat! Corn! Cotton! Moo-cows! Chickens! Tomatoes! Quiche!

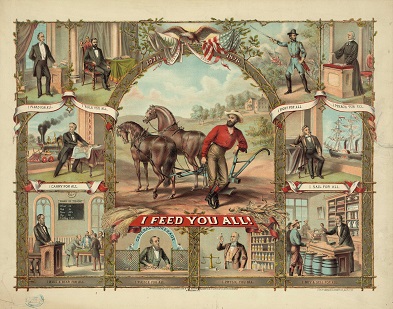

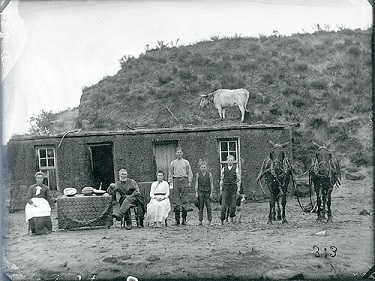

It wasn’t always a lack of production. Many farmers across the Plains were quite successful – at least in the traditional sense. They were growing and raising more good stuff than ever before! Wheat! Corn! Cotton! Moo-cows! Chickens! Tomatoes! Quiche!  Farmers already worked 365 days a year, sun-up to sun-down. They worked on Sundays, birthdays, Christmas, and when they were sick. They labored in the earth and cared for any animals they held, enduring drought and deluge, heat waves and freezes, in hopes of coaxing forth from the earth sustenance for themselves and the world.

Farmers already worked 365 days a year, sun-up to sun-down. They worked on Sundays, birthdays, Christmas, and when they were sick. They labored in the earth and cared for any animals they held, enduring drought and deluge, heat waves and freezes, in hopes of coaxing forth from the earth sustenance for themselves and the world.  They didn’t actually grow anything, or produce anything your kids could eat, or wear, or even that you could smoke, drink, or otherwise enjoy.

They didn’t actually grow anything, or produce anything your kids could eat, or wear, or even that you could smoke, drink, or otherwise enjoy.  Which meant, of course, that prices went even LOWER. In some cases, less than was necessary to break even. Some couldn’t pay back their loans. So, they renegotiated, perhaps borrowed more, bought more, raised more…

Which meant, of course, that prices went even LOWER. In some cases, less than was necessary to break even. Some couldn’t pay back their loans. So, they renegotiated, perhaps borrowed more, bought more, raised more… The Populist Party was born.

The Populist Party was born.