Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About Voltaire…

Three Big Things:

1. Voltaire (1694 – 1778) was one of the best known and most entertaining figures of the Enlightenment. He wrote philosophy and history and vigorously defended science and reason, but is best remembered for using his scathing wit in defense of the weak – their individual value and their natural rights.

1. Voltaire (1694 – 1778) was one of the best known and most entertaining figures of the Enlightenment. He wrote philosophy and history and vigorously defended science and reason, but is best remembered for using his scathing wit in defense of the weak – their individual value and their natural rights.

2. He was alternately embraced by the wealthy and influential and in very real danger from those whose pride he wounded. Unlike most great thinkers or artists, however, he had enough money that he wasn’t beholden to any of them for his sustenance.

3. Voltaire left behind dozens of books, hundreds of essays, plays, and short stories, and thousands of personal letters. The novella Candide is the most-read and referenced today, although his Letters on England, Treatise on Toleration, and Philosophical Dictionary are all readily available and accessible to modern readers.

Background

Voltaire was the pen name of François-Marie Arouet, although once he began receiving attention for his writing, he seems to have used the name pretty much full time. He was born into an upper middle-class family to a father working as a minor government official and a mother with claims to aristocratic ancestry and upbringing. His pre-fame life reads like YA fiction – plenty of teen angst, a father desperately wanting a better life for his son, and our young protagonist repeatedly straying from his assigned path in order to write.

His acerbic sense of humor and love of puncturing overinflated personages got him into trouble time and again, including time served in the Bastille (the notorious French prison which later played such a pivotal role in the French Revolution). Unable or unwilling to moderate his rhetoric, he continued to provoke until eventually banished to England.

When he wasn’t running for his life, though, he was quite the hit at parties. More than willing to schmooze those he didn’t despise, Voltaire was a favorite guest and respected confidant of noblemen, wealthy patrons, and celebrated philosophers of his day.

Voltaire in England

What began as a flight for safety became an extended awakening for Voltaire, who found himself enamored by Britain’s constitutional monarchy, their freedom of religion and of the press, and the culture’s liberal tolerance (by eighteenth century standards) of such a wide range of ideas and beliefs. He stayed for over three years, soaking in its politics, its society, and its philosophy – in particular the writings of John Locke and Isaac Newton.

Locke, of course, wrote the hugely influential “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding’ in which he argues that God gave man reason with which to figure things out rather than relying on distorted perceptions of divine will. Knowledge is built from experience, and careful attention – a radical departure from the idea that man is born with an innate understanding of God and morality. Locke would also prove one of the most influential political thinkers on the founding fathers of what would later become the United States, claiming that man is born “with a title to perfect freedom, and an uncontrolled enjoyment of all the rights and privileges of the law of nature, equally with any other man… not only to preserve his property – that is, his life, liberty and estate – against the injuries and attempts of other men; but to judge of, and punish the breaches of that law in others…”

Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica all but invented modern science. Most of us are vaguely familiar with his principles about motion and equal and opposite reactions, and at some point in our high school career we probably answered a quiz question or two about his explanations of gravity. He subsequently invented calculus, then physics, and in his spare time completely reshaped astronomy. He may have scribbled the first several verses of “Freebird” and outlined the idea of a kid bitten by a radioactive spider as a superhero, both while figuring out where babies come from. The point is, he was a big deal.

Locke and Newton were both recently deceased, but their writings and ideas were alive and irrepressible; while no one was calling it that yet, they’d sparked what would later be called “The Enlightenment.” Like the Algonquin Round Table or CBGB, western Europe was brewing up a batch of innovative, dangerous ideas which would quite literally change everything following.

The Philosophes

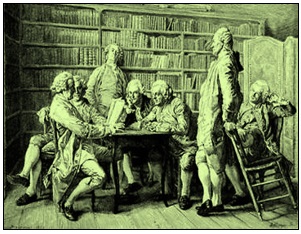

“Philosophes” is the French word for “philosophers,” but in the mid-18th century the term came to refer specifically to a breed of thinkers, speakers, and writers, who became the voices of the Enlightenment – Voltaire, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Ben Franklin, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Denis Diderot, and others. What identified the philosophes was not so much a specific doctrine or belief system, but a drive to apply logic and inquisitive criticism to pretty much anything worth discussing – philosophy, history, science, mathematics, politics, economics, social issues, etc. They wrote prolifically and read voraciously, and whenever possible they sat and drank and argued and wondered.

It was quite a time to be alive.

Of particular interest was the philosophes’ almost universal endorsement of social and political progress and religious tolerance. While not openly against religion, most – including Voltaire – were Deists. God, they believed, was akin to a clockmaker, who designed the world and all its wonders according to very specific (and sometimes rather complex) principles and natural laws. Once designed, he set it into motion and stepped back to let it play out as it may. Should one wish to improve or repair the clock, or some element thereof, there’s no sense crying out for the clockmaker. Rather, one must apply oneself to better understanding its functions and operations, so as to maintain or improve it effectively.

Voltaire, like most philosophes, did not trust religious authorities, or anyone who used power as an excuse to manipulate or harm others.

Major Works

Major Works

Voltaire was ridiculously prolific. He wrote major histories of Charles XII of Sweden, Peter the Great of Russia, and Louis XIV of France as well as numerous historical essays. He wrote poetry, and prose, and philosophy, and short stories, and letters – oh, the thousands and thousands of letters! He wrote essays on his time in England and his observations there, which got him into even more trouble in France and forced him to leave his native land yet again. He contributed to Diderot’s Encyclopédie, an ambitious gathering of all the world’s knowledge through the eyes of the philosophes and later compiled his own philosophical dictionary, both comprehensive and packed with personal commentary.

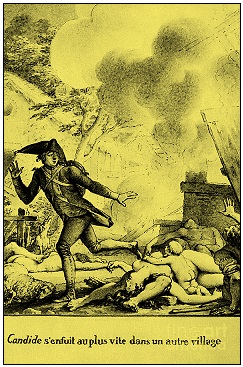

By far his best-known work is the novella Candide, or the Optimist, the story of a young man and those around him who experience an unending chain of human suffering and cruelty – none of it with apparent purpose or meaning. Candide was raised to believe all things work out for the best possible outcome (hence “the Optimist”), but as the story progresses, his efforts to reconcile such ideals with his experiences become increasingly absurd.

Like much of Voltaire’s writing, Candide is pithy and full of brash humor – at least, for its day. It’s not a complicated text, even centuries later, but there are few tweetable lines or knee-slapping scenarios of the type most familiar to modern audiences. It can be difficult to “explain the jokes” to modern readers if they don’t intuitively grasp the insanity in play. Most will, though, without real struggle – even if some outdated allusions and obscure subtleties are lost. Besides, it’s nice to think there’s something left for academics and experts to chuckle smugly over at their seminars.

Legacy

Voltaire is often remembered for a number of catchy things he never actually said. “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” is certainly consistent with his values, but there’s no record of his expressing it quite that way. “To learn who rules over you, simply find out who you are not allowed to criticize” captures his cynicism towards central authority but isn’t stated in any of his extant letters or published writings.

Fortunately, we can document enough of his meme-ready comments that we need not dismiss them all. “Those who can make you believe absurdities, can make you commit atrocities” is from an essay on miracles. “It is better to risk sparing a guilty person than to condemn an innocent one” is from one of his short stories. “If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him” is one of the most-quoted, as well as most easily misused or misunderstood. It’s a phrase taken from a larger argument about the role religion plays in helping society function smoothly; for all his cynicism, he wasn’t suggesting that God was fictional.

Voltaire epitomized so many things the modern progressive wishes to be – he was educated, he was outspoken, he was popular and respected (when he wasn’t being threatened or imprisoned)… and he was wealthy enough to get away with living as he pleased. He spoke truth to power and he used wit rather than weaponry to fight for truth and beauty as he understood it.

Not many of us can claim such a lifestyle, or such a legacy. Plus, he was a hit with the babes. You go, Volts.

Death

Voltaire died of natural causes in 1778, just after returning to Paris from one of his periods of exile. His brain and heart were removed and boiled in alcohol to preserve them for the ages – which was apparently a thing at the time. His brain was auctioned off not long after his death, and its location remains unknown. His heart is buried at the National Library of Paris, while the rest of him lies not so far away in the Panthéon mausoleum.

Voltaire preferred weightier topics, but he would no doubt have had some fun with such a macabre and messy postmortem. One of the great minds of the era was now… lost – and not just colloquially.

You Wanna Sound REALLY Smart? {Extra Stuff}

Excerpts from Voltaire’s Treatise On Tolerance (1763):

The fewer dogmas, the fewer disputes; and the fewer disputes, the fewer misfortunes: if this is not true, I am mistaken… It would be the height of madness to pretend to bring all mankind to think exactly in the same manner about metaphysics. We might, with much greater ease, conquer the whole universe by force of arms than subject the minds of all the inhabitants of one single village…

And, indeed, what can be more foolish, or more horrible than to address mankind in this manner: “My friends, it is not sufficient that you are faithful subjects, dutiful children, tender parents, and good neighbors; that you practice every virtue; that you are friendly, grateful, and worship Jesus-Christ in peace; it is furthermore required of you that you should know how a thing is begotten from all eternity and if you cannot distinguish the omousian in the hypostasis*, we declare to you that you will be burned for all eternity; and in the meantime we will begin by cutting your throats”? …

It does not require any great art or studied elocution to prove that Christians ought to tolerate one another. I will go even further and say that we ought to look upon all men as our brothers. What! call a Turk, a Jew, and a Siamese, my brother? Yes, of course; for are we not all children of the same father, and the creatures of the same God?

But these people despise us and call us idolaters! Well, then, I should tell them that they are very wrong. And I think that I could stagger the headstrong pride of {their most educated leaders} were I to speak to them something like this:

“This little globe, which is no more than a point, rolls, together with many other globes, in that immensity of space in which we are lost. Man, who is about five feet high, is certainly a very inconsiderable part of the creation; but one of those hardly visible beings says to some of his neighbors in Arabia or South Africa: Listen to me, for the God of all these worlds has enlightened me. There are about nine hundred millions of us little insects who inhabit the earth, but my ant-hill alone is cherished by God who holds all the rest in horror for all eternity; those who live with me upon my spot will alone be happy, and all the rest eternally wretched.”

They would stop me and ask, “What madman could have made so foolish a speech?” I should then be obliged to answer them, “It is yourselves”…

It is not only very cruel to persecute in this short life those who do not think in the same way as we do, but I very much doubt if there is not an impious boldness in pronouncing them eternally damned. In my opinion, it little befits such insects of a summer’s day as we are thus to anticipate the decrees of the Creator…

O different worshippers of a peaceful God! if you have a cruel heart, if, while you adore he whose whole law consists of these few words, “Love God and your neighbor,” you have burdened that pure and holy law with false and unintelligible disputes, if you have lighted the flames of discord sometimes for a new word, and sometimes for a single letter of the alphabet; if you have attached eternal punishment to the omission of a few words, or of certain ceremonies which other people cannot comprehend, I must say to you with tears of compassion for mankind: “Transport yourselves with me to the day on which all men will be judged and on which God will do unto each according to his works.”

* “the omousian in the hypostasis” – Voltaire is speaking sarcastically of the absurdly technical and detailed theological disputes popular among educated believers of his age. This particular one involved the logistics of the Trinity and the exact nature of Christ’s divinity vs. His humanity, etc.

From Candide, Chapter XXX, “The Conclusion”

Having said these words, {the old man} invited the strangers into his house; his two sons and two daughters presented them with several sorts of sherbet, which they made themselves, with Kaimak enriched with the candied-peel of citrons, with oranges, lemons, pine-apples, pistachio-nuts, and Mocha coffee unadulterated with the bad coffee of Batavia or the American islands. After which the two daughters of the honest Mussulman perfumed the strangers’ beards.

“You must have a vast and magnificent estate,” said Candide to the Turk.

“I have only twenty acres,” replied the old man; “I and my children cultivate them; our labor preserves us from three great evils—weariness, vice, and want.” Candide, on his way home, made profound reflections on the old man’s conversation.

“This honest Turk,” said he to Pangloss and Martin, “seems to be in a situation far preferable to that of the six kings with whom we had the honor of supping.”

“Grandeur,” said Pangloss, “is extremely dangerous according to the testimony of philosophers. For, in short, Eglon, King of Moab, was assassinated by Ehud; Absalom was hung by his hair, and pierced with three darts; King Nadab, the son of Jeroboam, was killed by Baasa; King Ela by Zimri; Ahaziah by Jehu; Athaliah by Jehoiada; the Kings Jehoiakim, Jeconiah, and Zedekiah, were led into captivity. You know how perished Crœsus, Astyages, Darius, Dionysius of Syracuse, Pyrrhus, Perseus, Hannibal, Jugurtha, Ariovistus, Cæsar, Pompey, Nero, Otho, Vitellius, Domitian, Richard II. of England, Edward II., Henry VI., Richard III., Mary Stuart, Charles I., the three Henrys of France, the Emperor Henry IV.! You know——”

“I know also,” said Candide, “that we must cultivate our garden.”

“You are right,” said Pangloss, “for when man was first placed in the Garden of Eden, he was put there ut operaretur eum, that he might cultivate it; which shows that man was not born to be idle.”

“Let us work,” said Martin, “without disputing; it is the only way to render life tolerable.”

The whole little society entered into this laudable design, according to their different abilities. Their little plot of land produced plentiful crops. Cunegonde was, indeed, very ugly, but she became an excellent pastry cook; Paquette worked at embroidery; the old woman looked after the linen. They were all, not excepting Friar Giroflée, of some service or other; for he made a good joiner, and became a very honest man.

Pangloss sometimes said to Candide: “There is a concatenation of events in this best of all possible worlds: for if you had not been kicked out of a magnificent castle for love of Miss Cunegonde: if you had not been put into the Inquisition: if you had not walked over America: if you had not stabbed the Baron: if you had not lost all your sheep from the fine country of El Dorado: you would not be here eating preserved citrons and pistachio-nuts.”

“All that is very well,” answered Candide, “but let us cultivate our garden.”

Major Works

Major Works Having said these words, {the old man} invited the strangers into his house; his two sons and two daughters presented them with several sorts of sherbet, which they made themselves, with Kaimak enriched with the candied-peel of citrons, with oranges, lemons, pine-apples, pistachio-nuts, and Mocha coffee unadulterated with the bad coffee of Batavia or the American islands. After which the two daughters of the honest Mussulman perfumed the strangers’ beards.

Having said these words, {the old man} invited the strangers into his house; his two sons and two daughters presented them with several sorts of sherbet, which they made themselves, with Kaimak enriched with the candied-peel of citrons, with oranges, lemons, pine-apples, pistachio-nuts, and Mocha coffee unadulterated with the bad coffee of Batavia or the American islands. After which the two daughters of the honest Mussulman perfumed the strangers’ beards.