Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About the Decalogue (aka, “The Ten Commandments”)

Three Big Things:

1. Moses and the Ten Commandments are foundational elements of both Judaism and Christianity and hold a revered place in Islam as well.

1. Moses and the Ten Commandments are foundational elements of both Judaism and Christianity and hold a revered place in Islam as well.

2. The Decalogue represents a “covenant” between a “chosen people” and a monotheistic deity. While the laws themselves are important, the larger historical impact is arguably the emphasis on covenant with a singular and omnipotent God – the idea of a special club in which membership is binary. You are either in or out.

3. The Ten Commandments themselves are a mix of religious commands and societal guidelines. None are entirely original, and they’re so bound up with the larger faith of which they’re a part that it’s difficult to identify their impact on legal codes apart from their religious significance.

Holy Moses

The story of the Ten Commandments is inextricably wound with the story of Moses, one of the most important religious figures in all of history. He’s a major player in Judaism, Islam, and Christianity, and presumed author of most or all of the Pentateuch – the first five books of the Old Testament.

The historical Moses is unfortunately rather difficult to pin down. Historians disagree as to his origins, his role in the Pharaoh’s household, and even whether or not he did half of what he’s best remembered for doing. In terms of historical significance, however, the “real” Moses is less important than the traditional or spiritual Moses. The Bible gives him a traditional hero’s origin story – born into a time of great troubles, his parents send him away for his own safety. (Orphans are also an option, although Moses’s story never begins that way.) He’s fortuitously adopted by caregivers who raise him and as he grows up, he discovers he has superpowers he uses to help the downtrodden and save the earth from Lex Luthor, because with great power comes great responsibility. He’s eventually has to make a choice between Slytherin (Egypt) and Gryffindor (the Hebrews) and with the help of a close friend or two, he changes the world – but not before the inevitable betrayal of many of those he’s trying to help.

Side Note: the fact that the traditional story of Moses fits so many archetypes doesn’t mean it’s not true. With ancient stories in particular, it’s difficult to know when the biography is made to fit the traditions or the traditions evolve from the actual biography. The stories of Moses suggest either that he was important enough to impact future tales of great men coming from humble beginnings, or important enough to have his beginnings reworked to fit traditional “great men” narratives. Either way, the lesson is that he was a pretty big deal and for all the best reasons – a template intentionally laid out for the inspiration and edification of those to follow.

While he’s the central figure (other than the Lord God, of course) in a number of memorable Old Testament stories – parting the Red Sea, calling forth water from rocks, and of course leading the Jews around the desert for forty-some years – but far the best-known is his ascent of Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments directly from Jehovah. Moses had already informed the Jews that they were God’s “chosen people” – something they’d hopefully figured out after the ten plagues the Lord called down on Egypt to persuade Pharaoh to let them go in the first place. He’d parted the Red Sea and they’d been following a pillar of smoke by day and a pillar of fire by night. Now it was time for the next step.

A Whole New Religion

Two things were significant about the Decalogue before the rules themselves are even revealed. One was that they were received from a solitary, unique God. Whether translated as Jehovah, Yahweh, the Lord, or whatever, there was no doubt that this God was singular and commitment to him exclusive. This was monotheism at its strictest, and the first two commandments would emphasize this even further. The second was the idea of “covenant.”

The God of the Old Testament was omnipotent and not much fun to deal with, but He repeatedly pursued relationships with his followers – albeit more businesslike than familial most of the time. He covenanted with Noah, then Abraham, and now Moses. “If you (the collective ‘you’) will follow Me and keep My commandments, I’ll bless you and protect you and it will be really quite swell, I promise.” The Ten Commandments were in some ways a synopsis of that contract.

The concept of a special covenant with or approved by God can be traced all the way down through the early Roman Catholic Church to the debates stirred up by the Protestant Reformation (can one “covenant” with the Lord directly, or must one go through his “people” to work it out?) and onto the shores of the early American colonies. The “City on a Hill,” the Great Awakening, right up through Imperialism and televangelism – if you’ll do this, God will do that. Don’t hesitate… this is a special offer not available to everyone.

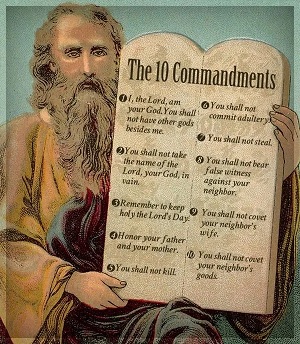

The Decalogue (c. 14th Century BCE)

These are better known as the “Ten Commandments” of Judaism, Christianity, and Charlton Heston. Unlike other ancient legal codes, these are very general statements of principle, presumably handed down by Yahweh directly to Moses, and recorded with only minor variations in both Exodus and Deuteronomy. There were plenty of other, far more detailed rules and procedures bearing the divine stamp recorded in these same books, but the Decalogue served as a sort of foundation or figurehead for all the rest.

The first four deal with the obligations of the chosen people (the Jews) towards their God:

1. No other gods before THE God (monotheism with an emphasis on the correct mono)

2. No “graven images” – idols, statues, etc. – representing the supernatural, especially for worshipping.

3. No taking the Lord’s name “in vain” (the meaning of this is subject to debate; it’s been construed as applying to everything from verbal outbursts to false oaths to attempting to harness supernatural powers).

4. Keep the Sabbath holy (no work on Saturdays/Sundays, depending on interpretation – that’s God’s day)

The second six deal with playing well with others – not just in your actions, but your attitude.

5. Honor your father and mother.

6. No murdering each other!

7. No adultery (sometimes understood to mean any sex outside of marriage).

8. No stealing.

9. No lying about your neighbor (generally understood to prohibit lying about most things).

10. Dial back the jealousy and lust – no “coveting” your neighbor’s wife, servants, home, or stuff.

As it turns out, the Hebrews waiting for Moses to return from Mount Sinai broke the covenant before he even had a chance to read them the new rules. As a result, Moses called on his priestly class to slaughter about 3,000 of his own people right then and there. This wasn’t a book club or Facebook group – the consequences of each individual’s choices were clearly going to be severe from the outset.

Historical Impact of the Ten Commandments

It’s difficult to evaluate the historical significance of the Decalogue for several reasons. First and foremost, the ideas expressed didn’t originate with Moses or the Jews, even if this particular expression of them was important to their larger story. “Don’t murder people” and “don’t steal” go way back and are generally applicable in most civilized societies, then as well as now. Secondly, the religious impact of the Ten Commandments and the larger narrative of which it’s a part was such that it far outweighs any potential cause-and-effect of the legal code element, even if it could be somehow removed or isolated from the rest.

The assertion of the monotheism mentioned above was important, as was the mixing of religious principles with civil or criminal law. The Decalogue wasn’t the first occurrence of either of these elements, but both are worth noting if analyzing the Ten Commandments or comparing them with other influential legal codes or religious canons. The suggestion that it’s not just outward behavior that matters, but on what we choose to focus or the attitudes we maintain towards others (whether parents, neighbors, or hotties) is interesting as well. Christianity would of course substantially build on this idea, but it was already there way back in the Old Testament – even if it did get a little lost among all the animal sacrifices and plagues from heaven and such.

Purely secular legal codes, of course, don’t generally attempt to punish citizens for what they’re thinking – at least not directly. There’s clearly no “separation of church and state” with Yahweh, which opens the possibility of some interesting comparisons to Islamic law many centuries later. While Europe was still sorting out the relationship between the Catholic Church and various kings and nobility, the Arab world saw far fewer distinctions, allowing them a degree of efficiency in matters of the law. Whether that was a net positive or negative is, of course, subject to discussion.

Beyond Secular History

Finally, of course is the role the Decalogue plays in modern Christianity. This is a tricky topic no matter how “academic” the audience, but generally speaking, the Commandments were (and are) foundational to Christianity’s proclaimed ideals, but fall short of accurately summarizing them.

Jesus said that he didn’t come to “abolish” the law, but to “fulfill” it. While this is obviously subject to a bit of interpretation, it reflects the idea that the Old Testament was in many ways a “prequel” for the New. In theory, the emphasis shifted from laws and rituals to love and relationships – from handwashing and sacrificing sheep to foot-washing and sacrificing self-interest. The law mattered, but love mattered more.

In reality, of course, the struggle between the “flesh” and its petty, vengeful, lusty feelings and a “spirit” more focused on peace on earth, goodwill towards men remains fairly universal, whatever one’s theology. Nor have we fully escaped the urge to claim “chosen” status – insiders with that special connection to Whoever’s in charge up there, stifling a smirk each time suffering and destruction reigns down on those outside the fold. The Decalogue remains an important part of one of the most important narratives in all of human history – one which assures us we can do better.