Trinity Lutheran v. Comer (2017): When Separation Becomes Discrimination

Three Big Things:

1. Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia v. Comer established that states cannot automatically exclude religious organizations from generally available programs or benefits simply because they are religious organizations.

2. The Court distinguished between funding religious activities (which states can refuse to do) and discriminating against religious institutions participating in secular programs (which they cannot do).

3. The decision significantly strengthened the Free Exercise Clause by ruling that any exclusion of religious organizations from neutral public programs should trigger strict constitutional scrutiny by the courts.

Introduction

Sometimes context is everything. Without it, the Trinity Lutheran case goes something like this:

Question: Can a church be allowed to benefit from a program available to a wide range of public institutions that has nothing to do with religion – for example, making playgrounds safer and nicer using recycled tires?

Supreme Court: Sure, that seems fair. No dangerous entanglement of church and state here.

And we move on.

Granted, it’s not quite that simple even without proper context – but it’s way, way messier once considered as part of a larger picture. At the risk of oversimplifying, it looks something like this…

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution opens with what are sometimes called the “Twin Religion Clauses”:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…

The first part is the “Establishment Clause”; the second is the “Free Exercise Clause.” In practical terms, these are generally understood to mean that Congress (and by extension, the federal government as a whole) is not allowed to do anything to promote a specific religious belief or the idea of religion in general but also not allowed to do anything to discourage a specific religious belief or the idea of religion in general. It is to remain as neutral as possible.

Sounds easy, right? In practice, however, it can quickly get messy. Consider the periodic kerfuffle over Christmas decorations. If a government entity (like a public school, or county, or state) puts up a Nativity scene, it’s technically pushing Christianity on the public using your tax dollars. If it sticks with snowmen and red-nosed reindeer, on the other hand, it’s arguably promoting a secular view of the holiday many find offensive. If it skips acknowledgement altogether, well… no one likes a government Grinch.

Just to complicate things further, American cultural dynamics and practical realities have a way of changing over time. Whether one considers the Constitution to be a “living document” or believes its words should be understood based exclusively on their intent when written, even the most fundamental rights exist in the tides of cultural mores and shifting expectations.

Sometimes context is everything.

The Context

In terms of religion and schools, there were four basic types of cases which reached the Supreme Court prior to Trinity Lutheran:

In terms of religion and schools, there were four basic types of cases which reached the Supreme Court prior to Trinity Lutheran:

1. Government-Sponsored Religious Activities In Schools

These are the ones with which most of us are at least generally familiar. Schools cannot lead students in prayer, read the Bible as scripture in class (the Bible as literature or history is fine), or otherwise sponsor religious instruction during school hours.

2. Religious Expression By Students Or Teachers

Despite popular misconceptions, there are few limits on student religious expression in school. As long as a student doesn’t disrupt learning time or otherwise subvert the smooth, safe functioning of the school, they can pretty much pray or talk about faith whenever and wherever they like.

Teacher expressions of faith are a bit trickier. Generally speaking, individual religious expression is balanced against perceptions of “endorsement” by the school (which is a government entity). What counts as balance is, of course, very context-specific. A high school teacher who wears a cross necklace or has a Bible on his bookshelf and answers students’ questions about his faith if asked is a very different dynamic than an elementary school teacher who prays at her desk during class and tends to only discipline students who don’t seem to share her beliefs.

3. Religious Content In Curriculum and Displays

Generally speaking, religious content is fine as part of the curriculum, whether in history, literature, art, etc. Displays of the Ten Commandments or Christmas musicals featuring religious songs or the Baby Jesus are not. Teachers and school officials are expected to make a reasonable effort to be respectful and accommodating of all genuine religious beliefs and to avoid pushing their own via words, decorations, or lesson plans.

4. Government Funding Of Religious Schools (Directly Or Indirectly)

This is arguably the trickiest variety of church-state separation in schools. Historically, it’s unconstitutional for government at any level to directly fund religious institutions or instruction. But what about AP Calculus textbooks? Bussing in areas where public school students ride city buses to school? “School choice” vouchers which allow parents to choose among the available school options – even if it’s a religious school?

Generally, the Court had determined that things like textbooks or public transportation to school were not violations of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. Most involved secular items and services which primarily benefited students – not the institutions themselves. The voucher thing is a bit more complicated, but when the Court had found them constitutional, it was largely because parents were choosing how to spend the funds – not the government.

At first glance, Trinity Lutheran would seem to fit in this last category, except for one little detail. The support in question wasn’t going to students directly, it was going to the religious institution. It wasn’t parents choosing to apply generally available resources, it was the government.

The Scrap Tire Program

Missouri, like many states, had a problem with old tires. Used tires pile up in landfills, create environmental hazards, and provide breeding grounds for mosquitoes and other pests. To address this issue, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources created the Scrap Tire Program, funded by fees imposed on new tire sales. The program offered grants to help nonprofits – including schools, daycare centers, and youth organizations – purchase playground surfaces made from recycled tires.

The program served multiple purposes: it reduced environmental waste, created safer play areas for children, and promoted recycling. Applications were evaluated on a competitive basis, with points awarded for factors like the poverty level of the surrounding area and the applicant’s plan to promote recycling awareness.

Trinity Lutheran Church operated a preschool and daycare center that served about 90 children aged two to five. The center was open to children of all faiths and functioned much like any other daycare facility, except that it operated under church supervision on church property. The playground was equipped with typical playground equipment, but the surface was covered with coarse pea gravel – the kind that can leave lasting impressions on small knees and elbows when children inevitably tumble.

In 2012, Trinity Lutheran applied for a grant under the Scrap Tire Program to replace the gravel with a safer rubber surface. The application detailed the safety benefits, noted that the playground served not just church families but the broader community, and explained how the project would promote recycling awareness. The center ranked fifth out of 44 applicants.

Despite its high ranking, Trinity Lutheran was denied funding. The reason was simple: it was a church. Missouri had a strict policy of categorically excluding any organization “owned or controlled by a church, sect, or other religious entity” from receiving grants under the program. This policy, officials explained, was required by Article I, Section 7 of the Missouri Constitution, which prohibited the use of public money “in aid of any church, sect or denomination of religion.”

The Constitutional Question

Trinity Lutheran sued, arguing that Missouri’s exclusion violated the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. The church wasn’t seeking funding for religious instruction or worship services – it wanted money for a safer playground surface. The program was entirely secular in nature, and Trinity Lutheran could fulfill all its requirements. The only reason for exclusion was the organization’s religious identity.

Missouri defended its policy by pointing to the long tradition of church-state separation and citing the Supreme Court’s decision in Locke v. Davey (2004). In that case, the Court had upheld Washington State’s decision to exclude devotional theology degrees from a scholarship program. If states could refuse to fund religious education, Missouri argued, surely they could refuse to fund religious organizations altogether.

The federal district court agreed with Missouri, as did the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit. Both courts found the case “nearly indistinguishable from Locke” and held that the Free Exercise Clause didn’t require states to include religious organizations in benefit programs.

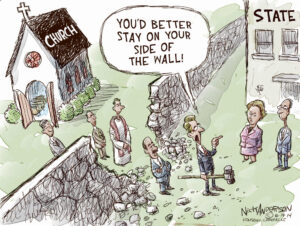

Along the way, the case caught the attention of the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF). The ADF is a pretty big deal in conservative legal efforts, especially in situations involving religious liberty and free speech. The good folks at Trinity Lutheran just wanted a better playground, and felt like they’d followed all the rules (which they had). ADF presumably recognized the larger potential of the case – chipping away at one particularly stubborn brick in the proverbial “Wall of Separation” which had so often been used to prevent anything hinting of publicly-funded support for religion.

The new and improved team representing Trinity Lutheran were convinced that this was an issue worth pursuing all the way to the Supreme Court – for the playground and for the principles behind it. Turns out they were onto something.

The Decision

The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case and ended up reversing the lower courts in a 7-2 decision in favor of Trinity Lutheran (and their playground).

Chief Justice Roberts, writing for the majority, went to great lengths to distinguish the case from Locke v. Davey. In Locke, the Court noted, the student who initiated the case was denied funding not because of who he was, but because of what he proposed to do – pursue devotional theological training. Washington’s scholarship program otherwise went “a long way toward including religion in its benefits,” allowing students to attend religious schools and even take theology courses, just not to major in devotional theology.

Trinity Lutheran’s situation was fundamentally different. The church wasn’t seeking funding for religious activities or training. It was seeking funding for playground resurfacing – a thoroughly secular purpose that was almost impossible to frame as “establishment (or support) of religion.” Missouri’s policy was flawed because it didn’t prohibit religious uses of public funding – it banned generally available services or programs from including religious organizations at all. “The rule is simple,” Chief Justice Roberts wrote. “No churches need apply.”

It was a fair distinction. Presumably, it would have been fine for the city to replace the sidewalks in the neighborhood near the church – thus facilitating people walking to church – or allow the fire department to respond should the church be ablaze. Government actions which incidentally assist religion aren’t the same as those which actively promote faith, or one faith over another. Trinity Lutheran hadn’t qualified for funding because they were a church; they’d qualified because they met the many requirements just like everyone else who was approved. At that point, denying them the playground improvements violated the Free Exercise Clause.

The Chief Justice put it a bit more loftily than that, of course. “Trinity Lutheran is not claiming any entitlement to a subsidy,” he explained. “It instead asserts a right to participate in a government benefit program without having to disavow its religious character.” When government forces such a choice between religious identity and public benefits, it imposes a penalty on the free exercise of religion that can only be justified by a compelling state interest subjected to strict scrutiny – and “there are only so many recycled tires” didn’t qualify.

Missouri’s interest in avoiding establishment problems, while legitimate, was not compelling enough to justify this kind of discrimination. They were effectively attempting to achieve a separation of church and state beyond what was already demanded by the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, and in so doing had run head first into the Free Exercise Clause next door.

The Dissent

Justice Sotomayor, joined by Justice Ginsburg, offered a sharply worded dissent that challenged both the majority’s reading of the facts and its framing of constitutional history. The stakes were far higher than recycled tires, she argued. This case was “about nothing less than the relationship between religious institutions and the civil government – that is, between church and state.”

The problem began with the very paradigm used by the majority to understand the facts of the case. This wasn’t about excluding a church from a secular program (like police protection or better sidewalks), this was directly funding religious facilities, the primary purpose of which was proselytization. The daycare and preschool facilities (of which the playground was a part) was described by the church itself as “a ministry of the Church” that incorporated “daily religion” into its program and was used to “teach a Christian world view” and “bring the Gospel message to non-members.” The playground wasn’t distinct from this religious mission – it was integral to it.

Sotomayor reminded both the majority and anyone else willing to listen of why the Framers had developed this careful separation between the religious and the governmental. The lesson was the same as that applied by the Court in a half-century before when confronted with school prayer and religious instruction in public schools. Founders like James Madison and many others who’d fought to end the public funding of religion “based their opposition on a powerful set of arguments, all stemming from the basic premise that the practice harmed both civil government and religion.”

Obviously it doesn’t do those outside the faith any favors when their own government finances beliefs with which they disagree, however indirect that support may be. But history strongly suggests that it doesn’t do the religion itself any favors, either – at least in the long term.

Sotomayor also challenged the majority’s legal reasoning. Rather than applying the strict scrutiny test the majority used, she argued that precedents like Locke v. Davey had established a more nuanced balancing approach when states chose to accommodate establishment concerns. The Court had previously recognized there was “room for play in the joints” between the two religion clauses, allowing states to exclude religious entities from some programs without violating the Free Exercise Clause.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, she warned that the majority’s decision created an dangerous precedent which could be “manipulated” in subsequent cases. By establishing that religious organizations could not be excluded from public programs based on their religious status, the Court had potentially opened the door to direct government funding of religious activities.

“This case,” she concluded, “is about nothing less than the relationship between religious institutions and the civil government – that is, between church and state. The Court today profoundly changes that relationship.”

The Playground Gates Are Open Now

The Court made a token effort to limit its ruling to the specific circumstances before it – albeit in a footnote:

3. This case involves express discrimination based on religious identity with respect to playground resurfacing. We do not address religious uses of funding or other forms of discrimination.

At least two other justices who agreed with the decision took issue with that footnote. In separate concurrences, Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch both expressed discomfort with the restraint suggested in Roberts’s footnote. Gorsuch’s argument echoed that of many opponents of state funding of religious institutions – even for playgrounds – as he noted the difficulty distinguishing between religious “status” and religious “uses” of resources. It’s a quandary which would surface repeatedly in subsequent cases (although usually on the other side of the argument).

That’s what made Trinity Lutheran so significant. Taken in isolation, the case really was about some fairly subtle distinctions between violating “Establishment” or violating “Free Exercise.” Few observers – even among the most progressive – would argue that the First Amendment required denying secular government services to churches just because they’re churches.

But Supreme Court cases are rarely decided in isolation – and they’re certainly not understood or applied in a vacuum. Advocates for greater religious “freedom” perked up at this sudden shift in the constitutional winds. Jurisprudence at the highest levels, it seemed, might finally be receptive to a dramatic rethinking of just how much support government could offer the already dominant belief system of the nation.

They weren’t wrong.

The Slippery Slope

In Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue (2020), the Court determined that the exclusion of religious schools from a state tax credit scholarship program violated the Free Exercise Clause. The majority cited Trinity Lutheran in its opinion and extended it from recycled tires to financial assistance to students. The state couldn’t simply exclude religious institutions. It was still a violation of “Establishment” to use public funds for religious purposes, but a violation of “Free Exercise” to withhold those funds based on religious “status.”

In Carson v. Makin (2022), the Court similarly found that a state tuition assistance program which excluded religious schools was unconstitutional. Trinity Lutheran and Espinoza were cited as precedents. The majority opinion this time questioned the very idea that the Court could meaningfully distinguish between religious “status” and religious “functions” as it had so often tried to do (just as Gorsuch had anticipated in his opinion for Trinity Lutheran). It was now unconstitutional to exclude religious uses of government money just as much as it was to exclude religious institutions.

Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022) wasn’t about government funding at all – it was about a football coach praying (often with students) on the 50-yard line after games. The Court’s decision in his favor, however, indicated an even greater affection for “Free Exercise” and an increasingly narrow definition of what it took to actually violate “Establishment” in the eyes of the Court.

Several lower courts have also cited Trinity Lutheran when religious organizations sought equal access to public programs – everything from historic preservation grants to COVID relief funds. The pattern shows the majority’s paradigm increasingly being extended to defend increasingly direct forms of religious funding and accommodation. The rapid transition from playground improvements to direct financing of religious instruction predicted by Justice Sotomayor unfolded more rapidly than either side could have anticipated. The slope was far slippier than most had realized.

Here’s hoping someone remembers the importance of a cushioned landing when we reach the end of the ride.