“Have To” History: Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022)

Matthew 6:1-6

Three Big Things:

- High school football coach Joseph Kennedy was placed on administrative leave after repeatedly leading post-game prayers at the 50-yard line that drew students, community members, and media attention, despite the district’s expressions of constitutional concerns and offers of alternative accommodations.

- The Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that the district violated Kennedy’s First Amendment rights, with Justice Gorsuch’s majority opinion describing Kennedy’s prayers as “quiet” and occurring while students were “otherwise occupied” – a characterization sharply at odds with the documented facts.

- The decision effectively eliminated the “Lemon test” that had governed Establishment Clause cases since 1971, replacing it with a “history and tradition” standard that significantly expands government accommodation of religious expression in public institutions.

Background – A Wall of Separation

By the time Kennedy v. Bremerton began garnering headlines, the Supreme Court had been wrestling with the appropriate relationship between church and state in public schools for nearly six decades.

The First Amendment contains two provisions related to religion. The Establishment Clause prohibits government from promoting religion or specific religious beliefs, while the Free Exercise Clause prohibits government interference with religious beliefs and practices (at least without a very good reason). On paper, they complement one another perfectly. In reality, the two goals at times come into conflict with one another – like tectonic plates shifting ever so slightly but producing earthquakes or mountains as a result.

In Engel v. Vitale (1962), the Court struck down state-sponsored prayer in public schools, even when that prayer was theoretically voluntary and relatively non-denominational. Abington School District v. Schempp (1963) eliminated devotional Bible reading. The Court went back and forth when it came to government support for religious schools, attempting to prevent overt funding of religious messaging while still offering equitable access to algebra textbooks or literacy support – things intended to benefit children rather than the institution itself.

These decisions sought to maintain the proverbial “wall of separation” between church and state in public education without restricting or disparaging the individual religious choices of students or their families. Schools could teach about religion as history or literature, but they couldn’t promote or endorse any particular faith. It wasn’t always an easy line to draw, and it didn’t always stay put once established.

Could schools display the Ten Commandments? (Usually no.) Could graduation ceremonies include prayers? (Depends on who’s giving them and whether students feel coerced to participate.) Could teachers wear religious jewelry or put Bibles on their desks? (Usually yes, as long as they weren’t proselytizing.)

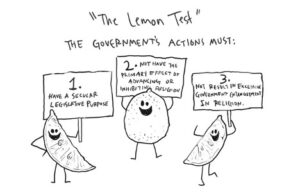

Along the way, the Court developed what became known as the “Lemon Test,” first applied by the Court in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971). The “Lemon Test” consists of three prongs. For a law to be constitutional, it must (1) have a secular legislative purpose, (2) neither advance nor inhibit religion, and (3) avoid fostering “excessive government entanglement with religion.”

While never universally embraced, Lemon was referenced regularly for the next 50 years – usually in cases involving state resources being used to support private religious education in some manner. It received a facelift in Lynch v. Donnelly (1984) when Justice Sandra Day O’Connor added what she called the “endorsement test” as a natural extension of the second prong: would the government action in question be perceived by a reasonable observer as government endorsement of religion?

So, hypothetically, if a high school football coach held an abbreviated revival service mid-field immediately following a game, which included players, local politicians, and community members who knew it was going to happen because it had been promoted ahead of time, a reasonable observer might believe religion was, in fact, being endorsed.

A Court wishing to validate such an action, it seems, would have two basic options: (1) deny the reality of what happened, or (2) reject the “Lemon Test” entirely and replace it with something more accommodating.

It might even do both.

Background

Joseph Kennedy presumably wasn’t trying to start a constitutional crisis when he took the job as assistant football coach at Bremerton High School in Washington State. He just wanted to coach kids and maybe share a little of his faith along the way. Kennedy had played football in college and served in the Marine Corps before finding his way to the Pacific Northwest. When he started coaching at Bremerton in 2008, he began a personal tradition of kneeling at the 50-yard line after games to offer a brief prayer of gratitude. It was quiet, it was personal, and initially, it was private.

Joseph Kennedy presumably wasn’t trying to start a constitutional crisis when he took the job as assistant football coach at Bremerton High School in Washington State. He just wanted to coach kids and maybe share a little of his faith along the way. Kennedy had played football in college and served in the Marine Corps before finding his way to the Pacific Northwest. When he started coaching at Bremerton in 2008, he began a personal tradition of kneeling at the 50-yard line after games to offer a brief prayer of gratitude. It was quiet, it was personal, and initially, it was private.

But high school football is a communal experience, and Kennedy’s prayers didn’t stay private for long. Players began joining him, first a few, then more. What started as a solitary moment of reflection became a team ritual. Parents and community members took notice – some appreciatively, others with concern. The district, on the other hand, did not. While it’s inconceivable that no one in authority noticed the trend over a period of seven years, they apparently chose not to make an issue of it.

It would later be revealed that Coach Kennedy had regular pre-game prayers with his players as well, a tradition which predated his time in the district. He had inspirational talks with students as well, many of which were strongly founded in his religious beliefs. Again, school administration and others in a position to protest remained officially silent year after year. Whether or not that was the right call is certainly debatable, but the district’s behavior hardly reflects institutional hostility towards faith – which was exactly how it would later be portrayed.

And Lead Us Not Into Escalation…

In September 2015, an opposing team’s coach mentioned to Bremerton’s principal that he’d observed the prayer ritual. This prompted the principal to confer with district officials, who in turn consulted district lawyers on the matter. They advised, based on a half-century of Supreme Court rulings, that such public prayers, led by a school official on school property during a school event, with students participating, could easily be considered a violation of the Establishment Clause. One upset parent or community member could trigger a lawsuit the district would almost certainly lose.

What happened next depends on who’s telling the story. The district said they approached Kennedy respectfully, offering him alternative ways to express his faith that wouldn’t create constitutional problems. They suggested he could pray privately in his office, or before or after games when students weren’t around, or even at midfield as long as he made clear that student participation was neither expected nor encouraged. The paperwork trail submitted once the matter went to court certainly supports this version of events, as far as they go.

Kennedy’s supporters, however, insisted on telling a different tale. In their version, the school district declared war on the coach’s basic right to pray, demanding he choose between his faith and his job. They portrayed the situation as another example of secular authorities trying to sanitize public life of any religious expression, no matter how brief or personal. The fact that the district had documented their accommodation efforts at every step – multiple letters offering alternatives, invitations to discuss other options, expressions of willingness to work with Kennedy – simply refused to stick. The counternarrative was simply too enticing.

Kennedy’s supporters, however, insisted on telling a different tale. In their version, the school district declared war on the coach’s basic right to pray, demanding he choose between his faith and his job. They portrayed the situation as another example of secular authorities trying to sanitize public life of any religious expression, no matter how brief or personal. The fact that the district had documented their accommodation efforts at every step – multiple letters offering alternatives, invitations to discuss other options, expressions of willingness to work with Kennedy – simply refused to stick. The counternarrative was simply too enticing.

The distinction mattered – or, should have, at least – because it shaped the nature of the case from a constitutional standpoint. Was this about preventing government endorsement of religion in a public school? A demonstration of hostility towards personal faith from those in leadership? An employer or government entity making every effort to accommodate someone’s beliefs? Even genuine efforts based in good will may sometimes fall short of passing constitutional muster, but intent still mattered.

At least it had in every related case until now.

The Paper Trail: From Accommodation to Confrontation

The district superintendent first sent Kennedy a letter in September 2015 acknowledging his “sincere religious beliefs” while explaining the constitutional concerns. The letter emphasized that Kennedy could continue praying, just not in ways that might be seen as school-sponsored religious activity.

Kennedy initially seemed willing to work with the district. He agreed to stop leading students in prayer and to avoid religious motivational speeches in the locker room. For a few weeks, it appeared they’d found a workable compromise.

But the issue had attracted outside attention. The First Liberty Institute, a religious liberty law firm with a penchant for the performative, contacted Kennedy and offered to represent him. They argued that the district’s restrictions violated his constitutional rights and that he should be free to pray whenever and wherever he chose, as long as the prayer was personal rather than official.

On October 14th, Kennedy’s new legal team sent the district a letter announcing he would resume midfield prayer at the October 16th game. As the day approached, Kennedy appeared on local news shows and actively discussed the issue on social media. By the time the October 16th game arrived, the story had garnered national news coverage, with helicopters circling overhead as Kennedy knelt for his post-game prayer. Students, parents, and community members rushed onto the field (knocking over several members of the band in the process) and joined him in what could only be perceived as a rather large demonstration of religious zeal centered around Coach Kennedy.

On October 14th, Kennedy’s new legal team sent the district a letter announcing he would resume midfield prayer at the October 16th game. As the day approached, Kennedy appeared on local news shows and actively discussed the issue on social media. By the time the October 16th game arrived, the story had garnered national news coverage, with helicopters circling overhead as Kennedy knelt for his post-game prayer. Students, parents, and community members rushed onto the field (knocking over several members of the band in the process) and joined him in what could only be perceived as a rather large demonstration of religious zeal centered around Coach Kennedy.

The event drew enough attention that a local branch of the Satanic Temple contacted the district demanding equal time for their “faith” to be represented. The district began coordinating with local police to ensure games didn’t devolve into complete chaos and increased its efforts to keep fans from entering the field – signs, robocalls, additional security, and the like.

On October 26th, ten days later, state representatives supporting Kennedy joined him on the field along with players from both teams and the usual masses from the stands (who apparently didn’t get the calls or see the signs). Again the media absorbed the spectacle. Again there was absolutely no doubt about the nature of the demonstration – or so a reasonable observer might conclude.

Faced with Kennedy’s defiance and the growing media circus, Bremerton placed him on administrative leave. The district cited not just the constitutional concerns, but the security issues created by the crowds and media attention. They’d had to call in additional police for the October 16th game, and the post-game rush to join Kennedy’s prayer had created safety hazards as the mob rushed the field.

Kennedy’s lawyers filed a federal lawsuit claiming violations of his First Amendment rights to free speech and free exercise of religion. The district countered that they’d offered reasonable accommodations and that their client had chosen confrontation over compromise. The long journey through the federal court system had begun.

Kennedy’s supporters continued to parade the issue as a solitary man of faith courageously standing up to government overreach. His critics saw a school employee flouting his employer’s reasonable accommodations and turning the whole thing into a media spectacle. The former had passion, and communal conviction, and all the drama of a noble cause. All the latter had were facts and reality.

It was hardly a fair fight.

The Lower Courts’ Decisions

The initial federal court decisions went against Kennedy. The district court found that Kennedy’s prayers, given their public nature and student participation, constituted government speech that could be regulated by his employer. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, ruling that Kennedy’s prayers while on duty as a coach constituted government endorsement of religion.

The initial federal court decisions went against Kennedy. The district court found that Kennedy’s prayers, given their public nature and student participation, constituted government speech that could be regulated by his employer. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals agreed, ruling that Kennedy’s prayers while on duty as a coach constituted government endorsement of religion.

The appeals court applied existing precedent strictly. Under cases like Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000), which had struck down student-led prayers over stadium loudspeakers at high school football games, Kennedy’s prayers were clearly problematic. The court noted that Kennedy was in a position of authority over students, that his prayers occurred at a school-sponsored event, and that students faced social pressure to participate (as evidenced by substantial parent testimony to that effect).

The Ninth Circuit also rejected Kennedy’s free speech arguments. He wasn’t being disciplined for his social media posts from home or holding prayer meetings in his home over the weekend. Government employees, the court noted, don’t have unlimited rights to express themselves while on the job. A public school teacher can’t promote political candidates in class, and a coach can’t use his position to advance religious messages, even if he frames them as personal expression.

Kennedy’s supporters were undeterred. The case had become a cause célèbre among religious conservatives, who saw it as emblematic of broader cultural conflicts over the role of faith in American public life. By this stage it had become clear that what was actually happening was no longer relevant – the symbolism was paramount. As the case reached the Supreme Court, it would be up to nine veteran justices to look past the rhetoric and weigh the actual circumstances in light of the law.

At least, that’s how it was supposed to work.

The Decision

The iconic Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan was fond of saying that in America, everyone has a right to their own opinion, but not to their own facts. In Kennedy v. Bremerton, the highest court in the land decided this was much too limiting an approach to adjudication. The Court had, of course, addressed the natural tensions between the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause before, often with some consideration of the Free Speech Clause as well. The results rarely made everyone happy, but most of the time the different sides at least agreed on which events were being evaluated.

Not this time.

Justice Gorsuch, writing for the 6-3 majority, began by reframing the factual narrative in much the same way kidnappers in the movies compose ransom notes – taking bits and pieces of various sources to cut-and-paste together an ominous new message. Gorsuch portrayed Kennedy as an individual engaging in private prayer that students occasionally chose to join, cut down by a district ignorant of the true intent of the First Amendment:

Justice Gorsuch, writing for the 6-3 majority, began by reframing the factual narrative in much the same way kidnappers in the movies compose ransom notes – taking bits and pieces of various sources to cut-and-paste together an ominous new message. Gorsuch portrayed Kennedy as an individual engaging in private prayer that students occasionally chose to join, cut down by a district ignorant of the true intent of the First Amendment:

Joseph Kennedy lost his job as a high school football coach because he knelt at midfield after games to offer a quiet prayer of thanks. Mr. Kennedy prayed during a period when school employees were free to speak with a friend, call for a reservation at a restaurant, check email, or attend to other personal matters. He offered his prayers quietly while his students were otherwise occupied. Still, the Bremerton School District disciplined him anyway.

The fact that virtually none of this was true did little to reduce its narrative appeal. It also gave the majority a pathway to reach what seemed to be their desired outcome – vindication for the humble man of faith standing up against systemic persecution.

Traditionally the Court would have begun by applying “strict scrutiny” of the situation, considering the district’s efforts at accommodation, and perhaps even referencing the “Lemon Test” as a guide. High school teachers certainly weren’t banned from all religious expression whatsoever; issues generally arose in situations involving coercion of students or perceived endorsement of religion by the school – that second “prong” of the “Lemon Test.” These were largely dependent on things like the age of the students, the nature of the perceived violation, and the responses of school officials when informed – hence the “strict scrutiny.”

The majority rejected this approach entirely, and with it generations of Establishment jurisprudence. In its place, the Court offered what it called a “historical practices and understandings” paradigm. This approach allowed a giant cross to remain in place at a World War I memorial, permitted town councils to have a moment of prayer before meetings, and retained the phrase “In God We Trust” on U.S. currency. The basic idea was that if something had been in place a long time without it creating a constitutional conflict, it was probably OK – especially if that something had taken on symbolism beyond the purely religious.

None of this was true of Kennedy’s post-game prayers, of course – every precedent of the past six decades said teachers leading students towards their faith of choice was very, very different than consenting adults deciding of their own free will to share a brief moment of traditional faith. But once the majority had rewritten the essential and well-documented facts of the case, it would have been silly not to misapply precedent as well.

The Court thus introduced a new understanding of “establishment” in which any concerns related to perceived government support of religion should be balanced against “traditional considerations.” Government should make every effort to accommodate individual religious expression, as long as that expression was consistent with what had been considered acceptable several generations prior. No one would be forced to participate, but neither could observers protest this perceived favoritism on the part of their government the way they might have in the past.

Lest this appear biased in favor of American Christianity, the Court clarified that every belief system would be treated the same, as long as it could demonstrate deep historical and cultural roots in the American story.

Lest this appear biased in favor of American Christianity, the Court clarified that every belief system would be treated the same, as long as it could demonstrate deep historical and cultural roots in the American story.

So, yeah – only if it were some popular version of American Christianity.

When Precedent Hands You Lemons…

Gorsuch condemned the “Lemon Test” specifically, arguing that it had been inconsistently applied and had created more confusion than clarity. Like his version of the events leading to the case before him, Gorsuch skipped the specifics and simply proclaimed it “long since abandoned” by the Court. There was no reason to debate its actual merits – the Court had probably overturned it already, remember?

With the “Lemon Test” effectively discarded and the new “historical practices and understandings” paradigm in place, demonstrating unlawful establishment would henceforth require evidence of overt threats or coercion towards those outside the faith. If some citizens are bothered by their government and their tax dollars supporting ideologies they consider offensive or dangerous, they need to get over it – because… traditions.

The perception by teenagers that their roles on the team might be influenced by whether or not they joined their coach’s religious activities were thus no longer relevant. Neither was the suggestion that teenagers in general tend to respond to peer pressure and might feel compelled to “join the crowd” at such events. Unless the Coach had formally required his students to participate or face explicit consequences, there was no constitutional violation here. Period.

As Gorsuch and the majority insisted on framing their decision, the district could regulate Kennedy’s “official duties” as a coach, but it couldn’t prevent him from engaging in personal religious exercise during his free time, even if that free time happened to occur on school property while he was still on the clock and legally expected to supervise his students and perform other professional duties.

A Strong Dissent

Justice Sotomayor’s dissent, joined by Justices Breyer and Kagan, called out the majority’s complete disregard for both facts and established case law. Kennedy wasn’t engaging in private prayer – he was creating public spectacles that drew media attention and encouraged student participation. His prayers occurred at the center of the football field immediately after games, when he was still on duty as a coach and still surrounded by his players. If this were somehow in question, multiple photos and news stories were attached as evidence.

More broadly, Sotomayor argued that the majority was eviscerating decades of carefully crafted Establishment Clause precedent. The decision, she wrote, “elevates one individual’s interest in personal religious exercise, in the exact time and place of that individual’s choosing, over society’s interest in protecting the separation between church and state.” If coaches can pray at midfield after games, what about teachers leading prayers before class? If religious exercise by government employees is protected whenever they claim it’s “personal,” how can schools maintain the religious neutrality the Constitution requires?

Yes, Sotomayor acknowledged, the founding generation engaged in various forms of public religious expression, but they also understood the dangers of mixing government authority with religious practice. The Establishment Clause wasn’t just about preventing coercion – it was about ensuring that government remained neutral on matters of faith.

Processing the Decision

The Court’s handling of Kennedy v. Bremerton was troubling beyond its extensive remodeling of the “Wall of Separation.” It appeared that a majority of justices, confronted by circumstances impossible to frame as an unconstitutional infringement on personal religious freedom, simply chose new circumstances more suitable to the desired outcome and debated them instead. This was an unexpectedly brash betrayal of everything the Court is intended to represent.

The Court’s handling of Kennedy v. Bremerton was troubling beyond its extensive remodeling of the “Wall of Separation.” It appeared that a majority of justices, confronted by circumstances impossible to frame as an unconstitutional infringement on personal religious freedom, simply chose new circumstances more suitable to the desired outcome and debated them instead. This was an unexpectedly brash betrayal of everything the Court is intended to represent.

Of course previous decisions had their detractors. There are often legitimate differences of opinion when it comes to intent, impact, or what this amendment or that act of legislation actually mean. If one wished to be generous, perhaps there were valid arguments to be made in Kennedy’s defense – that precedent had been too harsh, or that post-game prayers carry a symbolic value beyond the purely religious.

But weak as such approaches might have been, those weren’t the arguments. The Supreme Court based its overhaul of religious freedom on a narrative of its own design which the majority couldn’t possibly have believed to be factually true. In technical legal terms, they followed a judicial philosophy of “Nah nah nah nah! We can’t hear you! You’re not the boss of me!”

Religious enthusiasts in the general public at least had the excuse of distorted narratives or incomplete understandings of the First Amendment and how the system was set up to work as they celebrated their “victory.” The members of the Court knew better – and did it anyway.

Aftermath

Kennedy v. Bremerton reflects broader changes in the Roberts Court’s approach to religious liberty. Over the past decade, the Court has consistently ruled in favor of religious claimants, often at the expense of other constitutional values. Cases like Trinity Lutheran v. Comer (2017), American Legion v. American Humanist Association (2019), and Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue (2020) all expanded religious liberty protections. Where previous Courts often saw tension between promoting free exercise and avoiding establishment, the Roberts Court tends to see them as complementary. In this view, protecting religious exercise is always good, and concerns about establishment are often overblown.

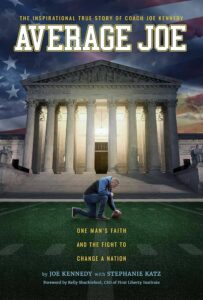

Kennedy himself moved to Florida during the litigation and took a job at a private Christian school. As the case worked its way through the courts, he secured a book deal, a movie deal, and became a conservative media celebrity (and remains so today). At every opportunity, he proclaimed coaching at Bremerton to be “the biggest honor of [his] life” and insisted he’d be “on the very first flight back” to Washington once the case was resolved. He didn’t want a spectacle – he just wanted his job back.

Once the Supreme Court issued its decision, Kennedy returned to Bremerton, where he coached one game and promptly resigned. He moved back to Florida and his private Christian school job and continues his role as a religious celebrity who was fired “because he knelt at midfield after games to offer a quiet prayer of thanks.” Even with the highest court in the land firmly in his corner, Ron Desantis on speed dial, and quality time spent with President Trump in the Oval Office, the story of the humble coach refusing to be crushed by the system is still too enticing to let go.