In November of 2017, Tyler Seguin’s name started popping up in hockey news headlines. That in and of itself is not so unusual; he’s a marquee player for the Dallas Stars and a damned pretty man. These headlines, however, were not about his on-ice skill or make-your-gate-swing-the-other-way smile…

They weren’t all quite that blunt….

You get the idea. So what had he said?

An ESPN reporter was doing a piece on the different languages spoken in NHL locker rooms. Most players managed something relatively diplomatic, others were insightful and well-spoken. Not so much my man Tyler:

Guys always talk in different languages. Sometimes you just put your foot down. We’re in North America, we’re not going to have a team of cliques.

Maybe not his best moment. He sounds so… American. (He’s not – Seguin is from Ontario. The one in Canada. Where millions of folks speak French.)

He wasn’t the only player to give an arguably “tone deaf” response, but his comments drew the biggest backlash. Then someone noticed that only a few months before, USA Today and the Boston Globe had both done pieces on the Boston Bruins, each citing the approach of team captain Zdeno Chara about such things:

He wasn’t the only player to give an arguably “tone deaf” response, but his comments drew the biggest backlash. Then someone noticed that only a few months before, USA Today and the Boston Globe had both done pieces on the Boston Bruins, each citing the approach of team captain Zdeno Chara about such things:

Bruins captain Zdeno Chara has a strict rule that every player, no matter where they’re from, needs to speak English in the locker room and on the ice.

Nine languages are spoken in the Bruins locker room: English, French, German, Slovak, Czech, Serbian, Russian, Finnish, and Swedish. And that doesn’t even count the Italian that defenseman Zdeno Chara – who can speak six languages – is learning for fun through Rosetta Stone… To make the communication go smoothly, to make sure no one is left out, there is only one universal language in the locker room. That’s English.

Chara recalled Anton Volchenkov, a teammate with Ottawa who now plays for the Devils. Volchenkov came to the NHL from Moscow. He was a nice guy, Chara said, willing to do whatever was needed. But he couldn’t speak English, and he struggled to fit in… ‘It really comes down to how much you want it. If you really want to stay, if you really want to learn, then you do whatever it takes – take lessons or hire a tutor or whatever that might be.’

And yet… no outrage. No criticisms. If anything, both pieces sang the praises of the Bruins’ locker room dynamics and of Chara in particular.

Why? What was the difference?

There are a few obvious things. While the gist of each comment was the same, Chara’s presentation was far more diplomatic. The bit about speaking English was part of a larger context about building team dynamics and the importance of mutual respect. Seguin’s comments came across as petty – maybe even snippy. They were part of a series of quotes about potential language problems among teammates.

Zooming out a bit, Chara is from Slovakia and speaks seven languages. He’d been in the NHL for twenty years at the time of the interview, over half of it with the Bruins, and he’s one of the most respected players in the game, on and off the ice. He still has the slightest bit of an accent, and while his most defining visual feature is that he’s about nine-and-a-half feet tall, you also can’t help but notice that he’s, you know… ethnic.

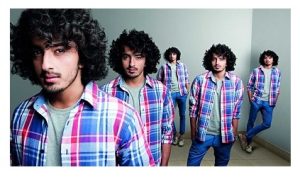

Seguin is tall, but in a normal-hockey-player kinda way. Between those smirking eyes and slightly-too-trendy beard, he looks, smiles, and struts like the bad boy for whom Rory Gilmore and her ilk will forever dump the earnest, dedicated lad who’d have otherwise loved them forever. Seguin had been in the league for about seven years at that point. He’d started with the Bruins (he and Chara won a Stanley Cup together) but was traded to Dallas amidst rumors of a party-boy lifestyle and lack of perceived commitment to the team, despite his elite skills. He’s also about as Caucasian as it’s possible to be without actually donning a MAGA cap and sidearm.

The point is, sources matter. What we know about a speaker, writer, or creator, shapes how we understand what they say, write, or create. Point of view – ours and our understanding of theirs – is everything.

In order to stabilize the world population, we must eliminate 350,000 people per day. It is a horrible thing to say, but it is just as bad not to say it.

Something from a younger, less-ambitious Thanos? Or maybe Al Gore during his failed Presidential bid, highlighting how out-of-touch he could be with that depressing environmental fixation of his? What if I told you it was actually St. Augustine, the revered Christian apologist, writing over a thousand years ago? Or Nelson Mandela? Or Barry Goldwater? Would it matter if it were Pope Francis or Hitler?

If you say the source doesn’t matter to how we read or react to something – that it’s secondary to a work’s quality or an idea’s merits, you’re lying. Or delusional. Maybe both. And you know I’m right because I’m the most reliable, entertaining, and profound source you’re reading at the moment.

It was Jacques Cousteau. If you’re over the age of forty, you just thought to yourself, “Oh, yeah – that explains it.” If under, it was probably closer to, “Who?”

Words build bridges into unexplored regions.

That one was Hitler, although it’s arguably taken out of context. It doesn’t make the statement false, but it sure changes the likelihood you’re going to use in on your next motivational poster, doesn’t it? (Then again, some very fine people on both sides, amiright?)

This sort of thing matters when we’re reading primary documents in history, and sometimes even when we’re using secondary sources. Author always matters, whether to better understand intent or more clearly analyze meaning. But it also matters when someone is trying to persuade us of something – maybe even more so.

The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.

This Thomas Jefferson classic is a favorite of militia members and gun nuts. It was on Timothy McVeigh’s t-shirt when he blew up the Murrah Building in Oklahoma City in 1995. It carries a punch it would lack if the author were, say, William Wallace, or even Thomas Paine. Jefferson was a Founding Father. He wrote the Declaration of Independence. He was a President, for gosh golly’s sake!

But understanding Jefferson means accepting his love of rhetorical flair over objective accuracy: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, and are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness…” is a marvelous statement of ideals, but hardly suitable as a practical foundation for statutory law. And in that same Declaration, Jefferson justifies revolution itself – “That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government…” It’s a powerful sentiment, but are you OK with your child’s high school history teacher promoting it as a practical solution to the Trump administration or a seemingly corrupt, inept Congress?

Ideas and words matter, all by themselves – absolutely. Books, music, art, fast food – I don’t always need to know the motivations and political ideologies behind every song I crank up or every chicken sandwich I grab from drive-thru. But let’s be honest with ourselves about the extent to which author and context shape our understanding or opinions when we’re not feeling particularly analytical or cautious. Our favorite person in the world might occasionally be an idiot, while someone of whom we’re not personally a fan may from time to time speak great wisdom.

Whether or not English should be spoken in the locker room is not an exclusive function of the degree to which Tyler Seguin sounded like a tool or Zdeno Chara came across as a great guy. It’s an issue which no doubt involves a range of factors, interwoven and no doubt varying widely from situation to situation. In other words, it’s not a simple ‘yes/no’ issue.

I respectfully suggest we tread lightly when judging education policy, teaching style, grading policies, discipline guidelines, and pretty much everything else in our weird little world. There are many likeable, well-spoken people whose ideas aren’t right for your kids – maybe not for anyone’s kids. Knowing a bit about who they are and what they want can go a long way towards helping us see past the shiny, tingly stuff they bring.

Beyond that, there are some iffy people in our world saying and doing things which aren’t always horrible. I, for one, keep stumbling across recent legal opinions by Justice Kavanaugh with which I substantially agree – despite cringing a bit at the internal dissonance which results. And just last month, a student sent me a Ben Shapiro video in which he said TWO ENTIRE THINGS which weren’t horrifying or insane.

I know, right?

Sometimes our favorites are wrong, and sometimes the most annoying people have questions or insights we’d do well to consider – even if they present them in the most tone deaf or irritating ways. Besides, there may be hope for them.

Speaking of which, Dallas has been good for Tyler. He’s a dedicated team player, plugged in with the community, active with charity work, and has a last-guy-off-the-ice work ethic. I don’t know his innermost being, but he seems like a decent enough fellow, despite his comments on language barriers.

Besides, he’s still SO pretty.

RELATED POST: Hockey Bias and Edu-Paradigms

RELATED POST: He Tests… He Scores!

RELATED POST: Stanley Cup Economics

Question: Every state has its own “law of the land” governing how things work within that state. What is this document called?

Question: Every state has its own “law of the land” governing how things work within that state. What is this document called? I can already hear my colleagues from the upscale suburbs eagerly explaining how I need to change my entire way of thinking about “school work.” Go ahead – get it off your chest.

I can already hear my colleagues from the upscale suburbs eagerly explaining how I need to change my entire way of thinking about “school work.” Go ahead – get it off your chest. The fun part comes when I find the exact text he’s used and point it out to him. Over half the time, students will insist that they didn’t copy from the internet. The similarity is purely coincidental – or perhaps the internet copied from them. Some grow quite agitated and defensive, which is either amusing or just weird, depending on how much sleep you had the night before.

The fun part comes when I find the exact text he’s used and point it out to him. Over half the time, students will insist that they didn’t copy from the internet. The similarity is purely coincidental – or perhaps the internet copied from them. Some grow quite agitated and defensive, which is either amusing or just weird, depending on how much sleep you had the night before. I’m not proud when I tell you that I’ve several times suggested to entire classrooms of students that they focus on copying from someone with a higher grade than themselves because I’m less likely to notice when more answers are correct. Sure, it was partly sarcastic – but only partly.

I’m not proud when I tell you that I’ve several times suggested to entire classrooms of students that they focus on copying from someone with a higher grade than themselves because I’m less likely to notice when more answers are correct. Sure, it was partly sarcastic – but only partly. There were essentially four major players in Africa in the latter half of the nineteenth century, at least in terms of our broad, offensively simplistic overview.

There were essentially four major players in Africa in the latter half of the nineteenth century, at least in terms of our broad, offensively simplistic overview. Cecil Rhodes was… complicated. It in no way excuses the wrongs for which he was responsible for us to recognize and appreciate the laudable elements of his story. If anything, it reminds us that in the right circumstances, most of us are quite capable of being both swell and abhorrent – sometimes within a very short time frame. While history is certainly replete with similar examples, Rhodes represents as well as anyone the futility of attempting to categorize our forebears into “good guys” and “bad guys.”

Cecil Rhodes was… complicated. It in no way excuses the wrongs for which he was responsible for us to recognize and appreciate the laudable elements of his story. If anything, it reminds us that in the right circumstances, most of us are quite capable of being both swell and abhorrent – sometimes within a very short time frame. While history is certainly replete with similar examples, Rhodes represents as well as anyone the futility of attempting to categorize our forebears into “good guys” and “bad guys.”