If for some strange reason you’ve not already read Part One several times already and copied favorite bits onto sticky notes to post around your bedroom and kitchen, I there waxed adoring over Helen Churchill Candee and her first extensive article about life in Oklahoma Territory, published in The Forum, June 1898. She wrote at least three other articles about O.T. in the time she lived there, all very positive towards her temporary homeland but varied in style and focus.

If for some strange reason you’ve not already read Part One several times already and copied favorite bits onto sticky notes to post around your bedroom and kitchen, I there waxed adoring over Helen Churchill Candee and her first extensive article about life in Oklahoma Territory, published in The Forum, June 1898. She wrote at least three other articles about O.T. in the time she lived there, all very positive towards her temporary homeland but varied in style and focus.

The shortest of these was published only a month after the Forum piece in Lippencott’s Monthly Magazine (July 1898). Lippencott’s had been around since just after the Civil War and was well-known for its literary criticisms, science articles, and other general-interest-type essays and stories. It’s the magazine which first published The Picture of Dorian Gray (Oscar Wilde) and which convinced Arthur Conan Doyle to write a second adventure (The Sign of the Four) featuring this “Sherlock Holmes” character he’d introduced a few years before.

You get the idea.

“Oklahoma Claims” takes a far more narrative format than her other O.T. essays, consisting largely of Candee’s (fictionalized?) account of riding out to a claim with a good ol’ boy named “Ollin” and his “buxom niece,” Leora. It’s dialect-heavy, somewhat humorous, and the closest of the four pieces to almost actually criticizing homesteaders or others in the Territory who took advantage of the system.

As we rode along over the red rutted roads that cross the prairies, Ollin remarked,—

“My woman won’t go to the claim, for she says if I ever get her there she’ll have to stay an’ hol’ it down. But that ain’t so, for we’ve lived there long enough every year to satisfy the law, an’ I’m just about ready to prove up and sell it.”

“That isn’t what ‘Uncle Sam’ gave it to you for, is it? Weren’t the claims given away so that each man could have a chance to provide a settled home for his family, and land enough to support them if well cultivated?”

Ollin’s leathery face wrinkled into a smile; his small blue eyes lost their habitual look of searching, which had been gained through years of prairie work with Indians, outlaws, and herds.

“Uncle Sam is an awful nice man,” he drawled, “but he’s got to sit up all night to be up early enough for Oklahoma folks. There’s slick ways of holdin’ down claims you’d never dream of…”

The “hundred an’ sixty” refers to acres, the standard size of a plot under the Homestead Act (1862) and generally followed for homesteads in O.T. Town lots, of course, were substantially smaller.

”There’s our girl, now,” and he glanced at the bovine maiden, who had, however, a shrewd look in her eyes and a general air of self-possession. “She’s got a claim up in the Strip, but she lives with my woman an’ me. Every two weeks she takes some one with her an’ goes to spend a Sunday. That’s an awful nice way to earn a hundred an’ sixty, ain’t it?”

I’d like to be the kind of reader who goes high road on stuff like “the bovine maiden,” but it’s funny and effective beyond its role as essentially a ‘fat joke.’ It implies much about the niece’s true personality and intellect – not all of it bad, certainly, but largely unflattering. Combine that with “a shrewd look in her eyes and a general air of self-possession” and we’ve got the sort of condensed characterization far more typical of a strong short story than an informational piece.

Still, we somehow keep getting informed:

“But I thought that the government demanded that a homesteader should improve the land,” I suggested.

“That’s right. Our girl’s nobody’s fool. She’s let her claim to a family who farms it an’ goes half on the profits,” he responded, with an admiring glance at the clumsy monument of shrewdness, whose ample form and voluminous drapery hid all of her wiry pony save hoofs, head, and tail.

Much like a political cartoon, painting the niece as comically obese implies she’s something of a ‘weight’ or burden on the system, or society. Perhaps lazy, perhaps dull, she’s the antithesis of everything an Oklahoma homesteader was expected to be – from her gender to her work ethic to her ability. Candee would never stoop to overtly suggesting such a thing, of course, but she makes sure that Ollin’s admiration for her is suspect throughout – not because he’s insincere, but because we recognize the general absurdity in his evaluations of both people and circumstances.

“You should have seen the day the Cherokee Strip was opened. She rode right in with the best of them, lickity-split through bush an’ timber an’ draws till she left most of ‘em behind, an’ then out she whipped her gun an’ a hatchet an’ began to chop the sprouts off a black-jack. ‘Whatcher doin’, Leora?’ I hollers as I was a scootin’ past. ‘Improvin’ my lan’!’ she yells back; an’ I’m blessed if that very thing didn’t save her when some feller tried to driver her off—that an’ her gun.”

That Leora – she’s a feisty one alright.

“Did you run for a claim in the Strip when you had one here in the original territory of Oklahoma?” I asked the question as a reproach, for I did not like to discovery chicanery in a son of the prairies.

“Yes, I run for one,” returned Ollin, with a sheepish laugh. “First, off I started in to help our girl, but when I saw her get so quick suited I looked out for number one. I got a mighty nice place, too, an’ set there four hours happy as a horned toad. Then four fellers come along an’ pointed their guns at me an’ tol’ me that was their claim and I’d better get off. So I got off. But it was a blamed shame. I had no more right to it ‘n you have, but they might ‘a’ let me alone till some feller come along I could sell it to. That was all I wanted.”

Now, Olin was an honest man, but who could resist the temptation to grab when a free grab-bag is opened by the government? Besides, the man who has once led a life of adventure can rarely settle down permanently to conventional regularity.

And there it is. Candee won’t deny the “chicanery” she observes, but neither will she generally condemn the individuals partaking in it. Ollin didn’t mean to violate the system – it just kinda happened. Who could resist the temptation when the government set things up in such a way? Besides, he’s an adventurer by nature – a knight errant, of sorts. Only not.

Clearly a Joss Whedon fan, Candee uses plot and humor to frame pith and poignancy, often at the most unexpected moments:

…{B}ut life on a claim is narrower than life in a city tenement. Fancy two rivals living on the same quarter-section, hating each other as bitterly as ever did contestants for a throne. For these the whole world is narrowed down to one hundred and sixty acres, and all evil is concentrated in the person of the other claimant.

Remember that both men have regarded his venture in a new country as the last throw of the dice, and to lose now means a living death. Brooding over the threatened loss, feeling that earthly happiness can be secured only by the removal of the obnoxious one, it is small wonder if some day one of the men is found murdered…

Well that turned dark rather quickly. Note, though, that yet again, circumstances drive vice – not the moral failings of the individual.

He has found the processes of the law too slow, and has exhausted his funds in lawyers’ fees. If neither the law nor the Lord would give relief, he must seek it with his own hands; he has a wife and children dependent on him; he is sure of the priority of his arrival on the claim; and so, persuaded by reason and crazed by apprehension, he kills his adversary.

And then we’re quickly back to Ollin and his corpulent niece, discussing their homesteading shenanigans. We’re left well-informed – a reader wishes to feel educated for having read, after all – but nonetheless sympathetic towards those not created by this universe to rest easily at the top of every food chain.

We’re left somehow caring about these desperate, backwards souls.

We’ll get a much-expanded and far more serious look at the Territory a few years later when she writes for the folks back east again. She’s also going to make a weird dis on bicycles.

Next time.

Helen Churchill Candee came to Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory (O.T.) in the mid-1890s, primarily drawn by its

Helen Churchill Candee came to Guthrie, Oklahoma Territory (O.T.) in the mid-1890s, primarily drawn by its  History is full of people.

History is full of people.

On January 29, 1850, Henry Clay proposed the Compromise of 1850 to Congress. It was a collection of five bills he said would help prevent further conflict between the North and the South. Texas gave up its claims to New Mexico and other areas north of the Missouri Compromise line and the U.S. took over their remaining debts. California was admitted to the Union as a free state. Utah and New Mexico would enter the U.S. under the principal of ‘popular sovereignty’ – meaning the people in each would vote for whether or not to have slavery. The slave trade, but not slavery itself, was banned in the District of Columbia. A much tougher Fugitive Slave Act was enacted.

On January 29, 1850, Henry Clay proposed the Compromise of 1850 to Congress. It was a collection of five bills he said would help prevent further conflict between the North and the South. Texas gave up its claims to New Mexico and other areas north of the Missouri Compromise line and the U.S. took over their remaining debts. California was admitted to the Union as a free state. Utah and New Mexico would enter the U.S. under the principal of ‘popular sovereignty’ – meaning the people in each would vote for whether or not to have slavery. The slave trade, but not slavery itself, was banned in the District of Columbia. A much tougher Fugitive Slave Act was enacted.  President Zachary Taylor died unexpectedly in July of 1850 of what seemed to be a stomach-related illness. Some suggested he may have been assassinated by pro-slavery southerners, and various theories have persisted into modern times. In 1991, Taylor’s body was exhumed and tests were done in an effort to determine whether or not he had, in fact, been poisoned. The science found no evidence of malicious behavior, but some question the results even today.

President Zachary Taylor died unexpectedly in July of 1850 of what seemed to be a stomach-related illness. Some suggested he may have been assassinated by pro-slavery southerners, and various theories have persisted into modern times. In 1991, Taylor’s body was exhumed and tests were done in an effort to determine whether or not he had, in fact, been poisoned. The science found no evidence of malicious behavior, but some question the results even today.  On July 10, 1850, Millard Fillmore was sworn into office as the 13th President of the United States. Neither expansionists nor slave-holders were generally happy with his publicly stated policies regarding slavery, although it would be wrong of me to try to speak for them or evaluate their reasoning.

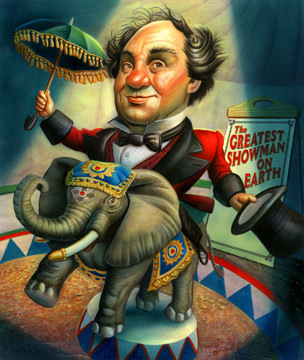

On July 10, 1850, Millard Fillmore was sworn into office as the 13th President of the United States. Neither expansionists nor slave-holders were generally happy with his publicly stated policies regarding slavery, although it would be wrong of me to try to speak for them or evaluate their reasoning.  On September 11, P.T. Barnum introduced Jenny Lind to American audiences. Often called the “Swedish Nightingale,” Lind was a soprano who performed in Sweden and across Europe before her wildly popular concert tour of America. She donated many of her earnings to charities, especially the endowment of free schools in Sweden. Some people think that sort of philanthropy is noble; others find it less so. Best we not consider such issues here. Or the role of the arts in influencing culture or character.

On September 11, P.T. Barnum introduced Jenny Lind to American audiences. Often called the “Swedish Nightingale,” Lind was a soprano who performed in Sweden and across Europe before her wildly popular concert tour of America. She donated many of her earnings to charities, especially the endowment of free schools in Sweden. Some people think that sort of philanthropy is noble; others find it less so. Best we not consider such issues here. Or the role of the arts in influencing culture or character. On August 22, 1851, a yacht named “America” won the first America’s Cup yach race, as things named “America” always should. This may have had an impact on different segments of the nation, or it may not have.

On August 22, 1851, a yacht named “America” won the first America’s Cup yach race, as things named “America” always should. This may have had an impact on different segments of the nation, or it may not have. December 1851 – The first Y.M.C.A. opens in Boston, Massachusetts. This arguably reflected changing values and social strategies in northern cities – if we were going to talk about values, I mean. Which we won’t. Because… school. So, um… the Village People recorded “Y.M.C.A.” in 1978 and it became a huge disco hit. If you’ve ever been to a live sporting event, you’ve heard this song and watched people do weird things with their arms which they seem to think are related to the song.

December 1851 – The first Y.M.C.A. opens in Boston, Massachusetts. This arguably reflected changing values and social strategies in northern cities – if we were going to talk about values, I mean. Which we won’t. Because… school. So, um… the Village People recorded “Y.M.C.A.” in 1978 and it became a huge disco hit. If you’ve ever been to a live sporting event, you’ve heard this song and watched people do weird things with their arms which they seem to think are related to the song.  1853 – America and Mexico signed the Gadsden Treaty. Vice President William King died. Arctic explorer Elisha Kane ventures farther north than any man has before.

1853 – America and Mexico signed the Gadsden Treaty. Vice President William King died. Arctic explorer Elisha Kane ventures farther north than any man has before.