Come now, you who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go into such and such a town and spend a year there and trade and make a profit”— yet you do not know what tomorrow will bring… Instead you ought to say, “If the Lord wills, we will live and do this or that.” As it is, you boast in your arrogance. All such boasting is evil. (James 4:13-16, English Standard Version)

I know, right? Not that I’m in any real danger of over-planning. It’s all I can do to keep track of today, let alone regiment tomorrow.

But I’m trying. At least in regards to the upcoming school year. I’ve been reading over standards, reviewing content, organizing visuals, bookmarking relevant articles or videos. Heck, I’ve even set up a calendar week on the new district student-learning-eduganza-management system, so that I know what we’re doing in class the first three or four days.

Possibly.

It’s always been hard for me to plan very far ahead – even when I’d been teaching the same thing for a number of years. The start of a new year is especially tricky, because, well…

I haven’t met the kids yet.

“Action has meaning only in relationship, and without understanding relationship, action on any level will only breed conflict. The understanding of relationship is infinitely more important than the search for any plan of action.” (Jiddu Krishnamurti, Philosopher & Speaker)

OK, I’ve met some of them. I had a few last year. It’s been a loooong time since I’ve had kids two years in a row (for different classes, not as retreads). Some of them will be happy to see me again, and I them. Others, not so much.

But I don’t know the class dynamics yet. I don’t have a “feel” for them yet. And that’s limiting in terms of just how ambitious I can be in preparing to beat the learnin’ into them.

It doesn’t help that last year didn’t go as well as I’d hoped. I moved to a new district in a new state to teach a new subject in a whole new reality stream. I love the new district, and the kids, and even the town. If only I’d not, you know… sucked so badly.

It doesn’t help that last year didn’t go as well as I’d hoped. I moved to a new district in a new state to teach a new subject in a whole new reality stream. I love the new district, and the kids, and even the town. If only I’d not, you know… sucked so badly.

OK, that’s not fair – I didn’t suck most days. What I did was spend far too much of the year trying to prove myself to a fictional audience (one deeply wedged in my subconscious and snacking on popcorn and emotional baggage, no doubt) before adjusting to the real kids in front of me – who weren’t ready for where I wanted to take them, and who didn’t trust me enough to go for it anyway. Once uncertainty and insecurity set in, well… it was a rocky start.

We finally reached a sort of groove, although in retrospect it, too, was distorted by dirty grace – a lenience built on guilt, like a divorced parent trying to “make up” to the 12-year old what he or she was unable to fix with their ex. I started off asking too much without figuring out where they were and finished by asking too little in an effort to offset whatever damage I thought I’d done.

All of which assumes I had much more control over the situation and the players than any of us really do.

“A deliberate plan is not always necessary for the highest art; it emerges.” (Paul Johnson, Historian & Author)

So perhaps “planning” isn’t the right word at all, so much as “preparing” – I hope to be better prepared this year. To have more options loaded and ready, to be more familiar with more content (which is essential if we’re going to be at all creative; “how” grows out of “what” and “why”), and to anticipate some of the time-intensive things I know I’d like to try, but wasn’t logistically able to construct before.

Most good teachers will tell you that it can take several years for your best lessons to evolve. Even then, that activity that totally churned the knowing and doing and growing for years in a row can suddenly just… not work anymore. Kids change. Different years are, well… different. Time to rework, rethink, re-valuate. You can’t always know ahead of time.

Still, you can prepare. We can prep ourselves, our ideas, our goals. We can prep the salads and the sauces and the skillets and the other chef-ish metaphor stuff I can’t quite pull together as I type – probably because I didn’t prepare to use them. (See what I did there?)

But you know what we can’t do – at least not consistently or effectively? We can’t plan it all, not really. Not honestly. Not effectively. Some of you can reach much further than I in your logistical outlines and have a much better idea what to expect based on your history in the district or with kids you’ve seen before. Nothing wrong with that. But the vast majority of us aren’t nailing down specifics until we’re in it – talking to the kids, watching them interact, asking them questions and otherwise pushing them as best we can.

Even when we’re in the middle of it, I’m not sure intuition and guesswork don’t play just a big of a role as knowledge and preparation. We can work mighty hard and it still seem like some of the best moments are a function of weird luck as much as anything.

Even when we’re in the middle of it, I’m not sure intuition and guesswork don’t play just a big of a role as knowledge and preparation. We can work mighty hard and it still seem like some of the best moments are a function of weird luck as much as anything.

Maybe that’s how it’s supposed to work – preparation creating the luck, and all that. I’d like to think we play some role in the mess. I’m positive that my kids do. Individually, and in how they react to and interact with one another. And events around them. And the weather. And the time of day. And their worlds. And their wiring. And the divine spark of random free will that keeps everything interesting and so damned difficult.

That’s not even taking into account their other teachers, other classes, and innumerable intangibles. You just never know what’s going to happen.

“In the planning stage of a book, don’t plan the ending. It has to be earned by all that will go before it.” (Rose Tremain, Author)

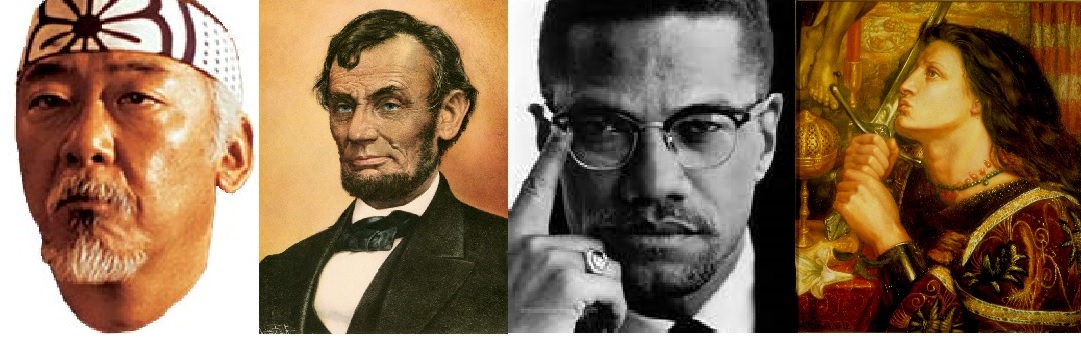

This, of course, drives ed-reformers and edu-financiers absolutely nuts. Folks accustomed to agenda-creation and content outlines and footnoted studies demand (but don’t really expect) better from those of us at the bottom of the pedagogical food chain. In their defense, many of them come from worlds awash in status, money, or influence (or some combination of the three). They are often accustomed to decreeing how things should go while others make it thus – or they’re at least surrounded by people good at pretending.

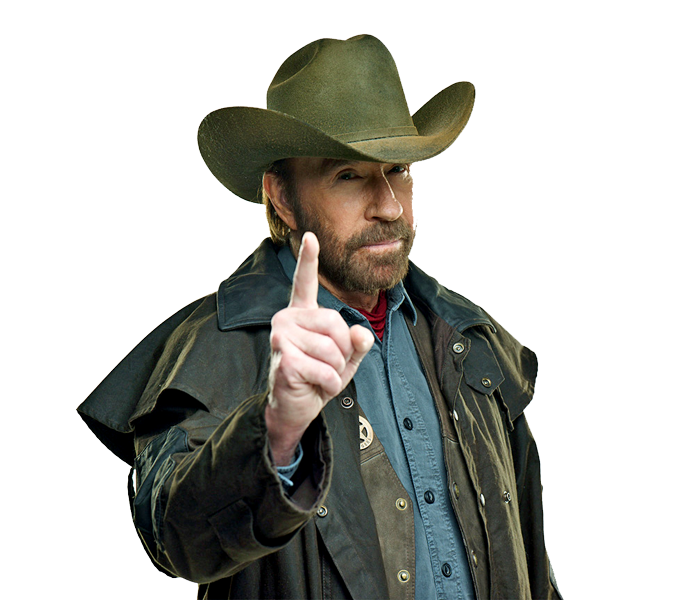

In my tiny little job, if things don’t go the way I’d hoped and planned, I usually know right away, and it’s immediately my problem and my scramble to adjust. As Peter Greene of Curmudgucation has pointed out, poor (or lazy) teaching brings on its own worst consequences – bored or antagonized teenagers, in your room, making you pay all day, every day.

Teachers are held accountable for innumerable things over which we have no control to begin with; we’re certainly not escaping the fallout of our own plans gone awry. It keeps you honest, I’ll tell you that.

I’m all for respecting expertise and I’m a big fan of having lots of money, but our culture too easily validates the pronouncements and preferences of power and prestige. Being rich doesn’t make you smart about everything – at best, it makes you smart about getting rich (although even that is often a function of circumstances or inheritance). And at the risk of sounding defiant or defensive, I’d even argue that being an “expert” in the field of education doesn’t mean you know anything about my kids or my content, let alone my classroom. You want authority? Tell me about your world and your experiences – your studies, your observations, your suggestions. I can adapt what’s useful for mine from there.

I have plenty to learn, even after twenty years. But any presentation, any training, any report, that opens with some variation of “stop ruining the future and behold my revelation of this season’s edicts” can pretty much kiss my aspirational posters.

If I were a nurturing, supportive type, I’d encourage you as the new school year ascends to prepare more than plan. Hold yourself to a much higher standard than is required by the paycheck or the system, absolutely – but cut yourself some slack when it comes to implementation and juggling the impossible and the unknown.

There will be real live little people in front of you soon, and they don’t need a better study or a more determined philanthropist – they need you to figure them out and to love them and to be stubbornly flexible on their behalf. Read the research and watch the TED Talks and follow the blogs, but own your gig and your obligations. We can demand far more of ourselves and of our little darlings without letting someone with a fancier title or a government study dictate exactly what that looks like in our reality with our kids.

No one knows better than you what’s best for your kids this coming year – a truth as terrifying as it is freeing. Anyone who claims otherwise is “boasting in arrogance.”

They’re coming. Let’s get prepared.

RELATED POST: The Sticker Revolution

RELATED POST: Ms. Bullen’s Data-Rich Year

RELATED POST: Am I Teaching To The Test?

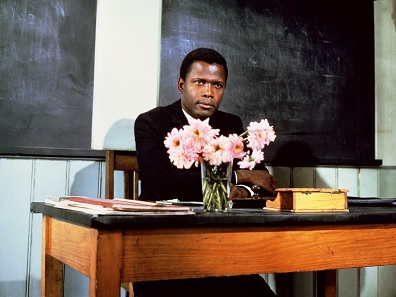

I was 29 years old when I did my student teaching. The first day I was with my new mentor, he asked me at lunch if I’d been paying attention as I sat in his classroom while he talked through whatever that day’s topic happened to be. I said I had. “Great,” he told me. “How ‘bout you take over after lunch?”

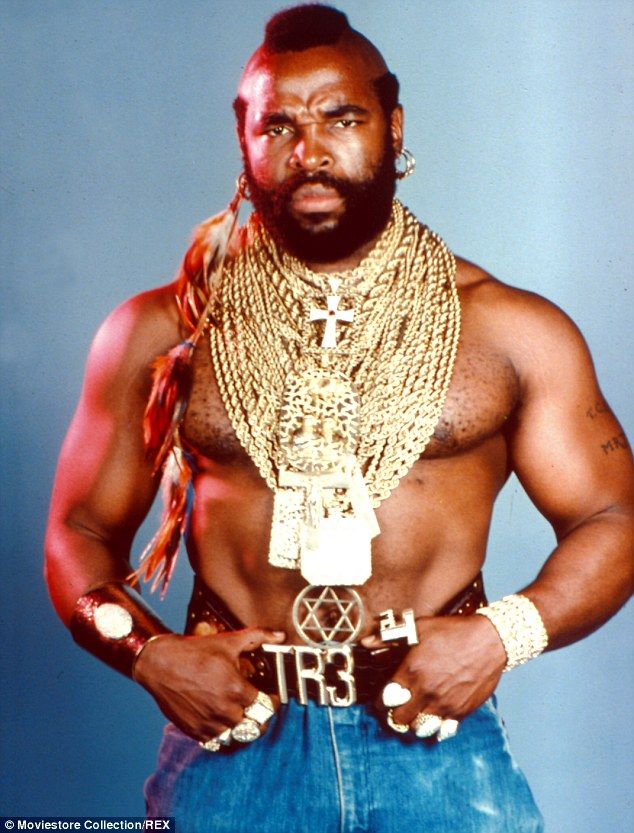

I was 29 years old when I did my student teaching. The first day I was with my new mentor, he asked me at lunch if I’d been paying attention as I sat in his classroom while he talked through whatever that day’s topic happened to be. I said I had. “Great,” he told me. “How ‘bout you take over after lunch?” I need to become a hard-ass. Or… hard-er, at least.

I need to become a hard-ass. Or… hard-er, at least.  I have some pretty reasonable policies regarding late work – if I followed them. They’re not particularly draconian. Anything skill-based can be attempted multiple times, and in some circumstances students can “earn” retakes of quizzes or whatever. There are enough grades throughout the year that a rough week or two isn’t enough to do lasting harm. Even poor test-takers should be fine if they take care of everything else.

I have some pretty reasonable policies regarding late work – if I followed them. They’re not particularly draconian. Anything skill-based can be attempted multiple times, and in some circumstances students can “earn” retakes of quizzes or whatever. There are enough grades throughout the year that a rough week or two isn’t enough to do lasting harm. Even poor test-takers should be fine if they take care of everything else.  Students are going to mess up. They’re going to get behind – which, in a history class, changes everything. If there’s going to be collaboration, or meaningful discussions, or if we’re going to go truly wild with some tasty primary sources or thesis-writing, there has to be SOME expectation that everyone is on the same proverbial (or literal) page, content-wise. Otherwise, they might as well all stay home and take the class online, dispelling the illusion that we’re a “class” and not just a bunch of people sharing classroom space here and there.

Students are going to mess up. They’re going to get behind – which, in a history class, changes everything. If there’s going to be collaboration, or meaningful discussions, or if we’re going to go truly wild with some tasty primary sources or thesis-writing, there has to be SOME expectation that everyone is on the same proverbial (or literal) page, content-wise. Otherwise, they might as well all stay home and take the class online, dispelling the illusion that we’re a “class” and not just a bunch of people sharing classroom space here and there.  There’s a good argument to be made for building personal responsibility and school skills and life skills as well via the relatively benign experience of actual deadlines and cutoffs; I haven’t even really wrestled with that aspect yet. Kannimayketup Swamp has pretty much dominated my concerns – probably because of all the damned irony involved.

There’s a good argument to be made for building personal responsibility and school skills and life skills as well via the relatively benign experience of actual deadlines and cutoffs; I haven’t even really wrestled with that aspect yet. Kannimayketup Swamp has pretty much dominated my concerns – probably because of all the damned irony involved.

Teacher retention is a… challenge – ‘challenge’ here meaning ‘nightmare-of-impossibility-dear-god-what-are-we-going-to-do?!?’

Teacher retention is a… challenge – ‘challenge’ here meaning ‘nightmare-of-impossibility-dear-god-what-are-we-going-to-do?!?’

Dear Engaged, Sincere, Loving, Active Parent(s):

Dear Engaged, Sincere, Loving, Active Parent(s): But you need to chill the $#&@! out.

But you need to chill the $#&@! out.

Here’s a news flash – the kids who aren’t feeling loved and validated at home do some pretty sketchy things to scratch that itch in other ways. Many of the ‘bad things’ from which you’re trying to shield them are – not unironically – manifestations of their desperate need for approval, to feel good enough, to be SEEN and HEARD.

Here’s a news flash – the kids who aren’t feeling loved and validated at home do some pretty sketchy things to scratch that itch in other ways. Many of the ‘bad things’ from which you’re trying to shield them are – not unironically – manifestations of their desperate need for approval, to feel good enough, to be SEEN and HEARD.  . Pick something specific they’ve accomplished – especially if they didn’t do it perfectly but worked really hard on it. That soccer game they lost by one goal, but busted their butts trying to stay in. That essay they actually started the day it was assigned (go figure!) but still didn’t get the grade they’d hoped. Kinda cleaning up without being asked. Being relatively patient with their sibling.

. Pick something specific they’ve accomplished – especially if they didn’t do it perfectly but worked really hard on it. That soccer game they lost by one goal, but busted their butts trying to stay in. That essay they actually started the day it was assigned (go figure!) but still didn’t get the grade they’d hoped. Kinda cleaning up without being asked. Being relatively patient with their sibling.  I know you want them to get into a good college, hopefully with some scholarship action. I know you want them to have good lives, good careers, to hang out with the right people and make the best choices. I’m not being sarcastic when I thank you for this; I have far too many kids whose parents aren’t nearly so concerned.

I know you want them to get into a good college, hopefully with some scholarship action. I know you want them to have good lives, good careers, to hang out with the right people and make the best choices. I’m not being sarcastic when I thank you for this; I have far too many kids whose parents aren’t nearly so concerned.