Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To)

Three Big Things:

1. The tribes of the Great Plains faced confinement or extermination as the 19th century drew to a close; they were desperate and confused in the face of ongoing U.S. expansion, aggression, and manipulation.

1. The tribes of the Great Plains faced confinement or extermination as the 19th century drew to a close; they were desperate and confused in the face of ongoing U.S. expansion, aggression, and manipulation.

2. The “Ghost Dance” promised to bring back their former way of life, to raise their dead, and to bring peace and prosperity to all who believed.

3. Variations in tribal interpretations of “Ghost Dance” teachings and white fears of Amerindian uprisings led to unnecessary death and violence, most notably at Wounded Knee in 1890 – the effective end of Native resistance on the Great Plains.

Background

The end of the American Civil War allowed the U.S. to turn its military focus to the Great Plains. The Homestead Act (1862) codified and intensified the westward expansion which had been a defining feature of the United States since its political birth a century before. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 had largely cleared the southeastern portion of the continent of its Native American inhabitants, most famously the Five Civilized Tribes, who were forcibly settled in Indian Territory (I.T.), along with a number of lesser-known tribes, where they did their best to rebuild what lives they could in this strange new land.

When the Civil War broke out, the Five Civilized Tribes largely supported the Confederacy – some wholeheartedly, others in part. Upon Union victory, Congress – controlled by the same Radical Republicans who would try so intently to “reconstruct” the South – punished the inhabitants of I.T. by drastically reducing their land allotments. The Five Tribes were confined to what is today the eastern half of Oklahoma, thus opening the western half to a new round of forced migration. This time it would be the tribes of the Great Plains – roughly the middle third of the U.S. – who would be hunted, cajoled, or otherwise forced onto this ever-shrinking reservation.

The Post-Bellum Indian Wars

The U.S. used a variety of tactics against the Plains Tribes in the decades after the Civil War. A favorite of George A. Custer was the early morning winter attack. Soldiers would surprise a village of “hostiles,” bundled with their women and children against the cold, and open fire just before dawn. Startled warriors were caught without their horses, weapons, or even clothing, and were generally slaughtered with relative ease.

A second strategy was less direct but arguably even more effective. Buffalo were essential to cultures and basic survival of most Plains Amerindians. Food, clothing, tools, storage, and rituals all involved parts of this ubiquitous beast. The U.S. began encouraging large-scale hunting of these creatures, on horseback or – no joke – by railroad. Excited urbanites paid good money for the chance to lean out of train windows firing rifles into the herds. The carcasses were often left in the sun to rot.

Then, of course, there were the actual battles between U.S. soldiers and various Plains tribal groups. There were a few Amerindian victories – most notably the Battle of Little Bighorn (aka, “Custer’s Last Stand”) in 1876, but by and large the Native Americans adapted poorly to the sort of hierarchical structure and sustained discipline essential for U.S.-style military engagement. While brave and creative warriors, they carried a deeply-rooted sense of individuality and a distaste for telling other men what they could or could not do. However much this stirred the romantic notions of distant whites, it completely undermined efforts to coordinate large-scale resistance.

In short, the U.S. had them out-numbered, out-gunned, out-financed, and out-structured. By the late 19th century, few Amerindians of any tribe could claim much hope for their collective futures.

The First Ghost Dance: Wodzibob

Around 1870, a Paiute holy man by the name of Wodzibob began sharing a vision he’d had in which God had taken him up to heaven and informed him that a time of resurrection was soon coming. The dead would be resurrected and the buffalo would return. The people could help speed this by performing a series of rituals, most notably an extended dance involving the entire community, women as well as men, moving rhythmically in a large circle.

“Round dances” were not new to the Plains Amerindians; most tribes had their own variations. Dancers sometimes entered trance-like states leading to visions or prophesies, so while Wodzibob’s message was new, the format and source were familiar. It was left to the individual to decide the extent to which someone else’s revelation applied to them. As an established healer and respected member of the tribe, Wodzibob’s teachings spread quickly and endured for several years, until it gradually became clear his predictions were not coming to pass in the promised time frame.

The Second Ghost Dance: Wovoka

The Second Ghost Dance: Wovoka

By the late 1880s, the majority of the tribes native to the continental United States had been defeated – by warfare, by disease, by the loss of land, and – in the case of the Great Plains – the disappearance of the buffalo. Many were forced onto reservations or packed into Indian Territory where they were expected to farm and practice “white” lifestyles on unwilling land, without essential tools or adequate supplies, and minus the requisite desire. The provisions “guaranteed” by the U.S. government either never arrived or were of such poor quality as to prove useless. The proud nations of the Great Plains were broken and bewildered, and quite possibly nearing extinction.

In January 1889, an emerging Paiute spiritual leader named Wovoka (aka “Jack Wilson”) claimed to have experienced a vision reminiscent of Wodzibob’s two decades before. Wodzibob’s teachings and experiences would have been familiar to Wovoka, both as recent tribal history and because his father had been a close associate of the revered shaman, so it’s probably no surprise the basic message was the same: those who’d been lost would soon return, as would their way of life, so have faith and dance.

Wovoka’s message, however, reflected additional influences, particularly his exposure to Christianity. Wovoka taught that the people should love one another, avoid stealing or lying or even fighting the whites, and do their best to live in peace even with those who had abused them. Tribal rituals involving self-mutilation were condemned, although by some accounts Wovoka punctured his hands – a “self-inflicted stigmata” to reflect his role as either the prophet of the returning Christ, or perhaps some form of the Messiah himself.

There was also a bit where God put Wovoka in charge of the weather, at least in the western half of the United States. That’s the tricky thing about visions and faith and conflicting primary sources – they make history so much more interesting but also so… messy.

The Wounded Knee Massacre

As tends to happen with ideas as they spread, Wovoka’s message quickly evolved as it was taken up by different tribes. With the Lakota Sioux in particular, it took on a more militant tone. Their concept of renewal – of heaven on earth – was incompatible with the presence of white folks, despite Wovoka’s calls for racial unity. It was also most likely a Lakota who added the idea of a “ghost shirt,” which would render its wearer impervious to bullets (since, presumably, you can’t shoot ghosts). It was exposure to the Sioux version of Wovoka’s visions which most led to white characterizations of the dance at the heart of the movement as a “Ghost Dance” with militant overtones.

As tends to happen with ideas as they spread, Wovoka’s message quickly evolved as it was taken up by different tribes. With the Lakota Sioux in particular, it took on a more militant tone. Their concept of renewal – of heaven on earth – was incompatible with the presence of white folks, despite Wovoka’s calls for racial unity. It was also most likely a Lakota who added the idea of a “ghost shirt,” which would render its wearer impervious to bullets (since, presumably, you can’t shoot ghosts). It was exposure to the Sioux version of Wovoka’s visions which most led to white characterizations of the dance at the heart of the movement as a “Ghost Dance” with militant overtones.

As U.S. concern over a possible Sioux uprising simmered, they more and more saw the dance as inherently hostile, or even preparatory for war. It was this fear that led to the arrest and subsequent death of Sitting Bull in 1890, a few weeks before Christmas. U.S. military officials next targeted a Lakota chief by the name of Big Foot. Most of his followers were women and children whose men had been killed resisting U.S. aggression. As those who’d lost the most, they were often the most devout adherents of the dance, pushing themselves until they collapsed or became otherwise incoherent.

Big Foot had led his group to the Pine Ridge Reservation to surrender. They were told to set up camp while officials figured out what to do with them next. The next day, December 29th, 1890, soldiers were sent into the camp to gather any remaining weapons among the Sioux. It’s unclear to what extent the Lakota resisted. Some accounts refer to a medicine man encouraging them to don their “ghost shirts” and fight, while others focus on a single young Sioux, probably deaf, who attempted to retain his rifle. Whatever the specifics, at some point a shot was fired and things pretty much went to hell from there.

Big Foot had led his group to the Pine Ridge Reservation to surrender. They were told to set up camp while officials figured out what to do with them next. The next day, December 29th, 1890, soldiers were sent into the camp to gather any remaining weapons among the Sioux. It’s unclear to what extent the Lakota resisted. Some accounts refer to a medicine man encouraging them to don their “ghost shirts” and fight, while others focus on a single young Sioux, probably deaf, who attempted to retain his rifle. Whatever the specifics, at some point a shot was fired and things pretty much went to hell from there.

Soldiers opened fire on the camp while panicked Sioux tried to grab what weapons they could to fight back. When the shooting stopped, 153 Lakota and at least 25 soldiers were dead. Most of the U.S. deaths appeared to be the result of “friendly fire,” which would be consistent with the sort of panic that comes after weeks of creeping paranoia.

Aftermath

Although periodic smaller conflicts would continue for a time, the Massacre at Wounded Knee marks the effective end of “Indian Resistance” on the Great Plains. Seemingly rubbing salt into the tragedy, the U.S. awarded twenty medals of honor to surviving soldiers for their actions.

As news of events at Wounded Knee spread, reactions were mixed. Some saw the military’s behavior as a gross overreaction – further abuse of a people clearly already defeated and pacified. Whatever the extent of the backlash, it did result in temporary efforts by the U.S. to more consistently honor its treaty obligations with survivors.

It would be nearly a century before American Indian groups began actively reclaiming their status and tribal identities.

The Second Ghost Dance: Wovoka

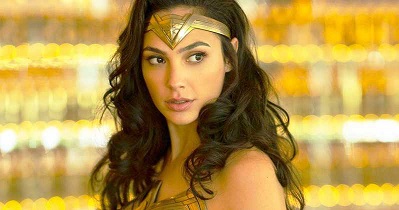

The Second Ghost Dance: Wovoka I’m a sucker for superhero movies. They’re a sub-genre of sci-fi, and the best sci-fi takes us out of our reality, out of our time and place, to better comment on that reality and force fresh eyes on our time and place. A good superhero picture isn’t about the cool powers and mega-battles; it’s about becoming better versions of our boring ol’ selves.

I’m a sucker for superhero movies. They’re a sub-genre of sci-fi, and the best sci-fi takes us out of our reality, out of our time and place, to better comment on that reality and force fresh eyes on our time and place. A good superhero picture isn’t about the cool powers and mega-battles; it’s about becoming better versions of our boring ol’ selves. I can’t speak with any authority about how faithful it is or isn’t to the comics. I was more of a Spider-Man and Fantastic Four guy, so Lynda Carter was about as close as I got to really knowing this character before now. So it’s this recent movie version of Wonder Woman, and the ethos surrounding her, that fascinates me at the moment.

I can’t speak with any authority about how faithful it is or isn’t to the comics. I was more of a Spider-Man and Fantastic Four guy, so Lynda Carter was about as close as I got to really knowing this character before now. So it’s this recent movie version of Wonder Woman, and the ethos surrounding her, that fascinates me at the moment. Granted, in this context the words are literally true. Diana – our “Wonder Woman” – is supernaturally created to fight the God of War and Human Corruption. But they’re also universal – especially for so many of our young ladies. As a culture, we’ve indoctrinated them to doubt everything about themselves, insisted they remain weak, and exploited them as part of our fallen nature.

Granted, in this context the words are literally true. Diana – our “Wonder Woman” – is supernaturally created to fight the God of War and Human Corruption. But they’re also universal – especially for so many of our young ladies. As a culture, we’ve indoctrinated them to doubt everything about themselves, insisted they remain weak, and exploited them as part of our fallen nature. Once highlighted, this message is everywhere in the picture. The next time you watch it (and you know you will), notice moments like this one in the trenches of WWI as Steve Trevor tries to argue with our hero:

Once highlighted, this message is everywhere in the picture. The next time you watch it (and you know you will), notice moments like this one in the trenches of WWI as Steve Trevor tries to argue with our hero: Diana, of course, decides to join him, convinced that “if no one else will defend the world from Ares, then I must… I am willing to fight for those who cannot fight for themselves.” She does not yet know that she is chosen for this; it is duty, made by choice, which drives her. Her mother explains that if she leaves, she can never return – literally true in Amazon mythology, but universally true of any meaningful journey. Whatever we set ourselves to do, once we step out, we will be forever changed in some way. None of us can ever go home – not in the sense of returning from where we came. We’ve changed. It probably has, too.

Diana, of course, decides to join him, convinced that “if no one else will defend the world from Ares, then I must… I am willing to fight for those who cannot fight for themselves.” She does not yet know that she is chosen for this; it is duty, made by choice, which drives her. Her mother explains that if she leaves, she can never return – literally true in Amazon mythology, but universally true of any meaningful journey. Whatever we set ourselves to do, once we step out, we will be forever changed in some way. None of us can ever go home – not in the sense of returning from where we came. We’ve changed. It probably has, too. Everywhere Diana goes are people (and animals) suffering who don’t deserve to suffer. Corruption hurts everyone, not just the bad people. Or maybe it does – maybe we’re all ‘the bad people.’ As events begin to unravel (an essential part of any hero’s journey), Wonder Woman begins to doubt…

Everywhere Diana goes are people (and animals) suffering who don’t deserve to suffer. Corruption hurts everyone, not just the bad people. Or maybe it does – maybe we’re all ‘the bad people.’ As events begin to unravel (an essential part of any hero’s journey), Wonder Woman begins to doubt…

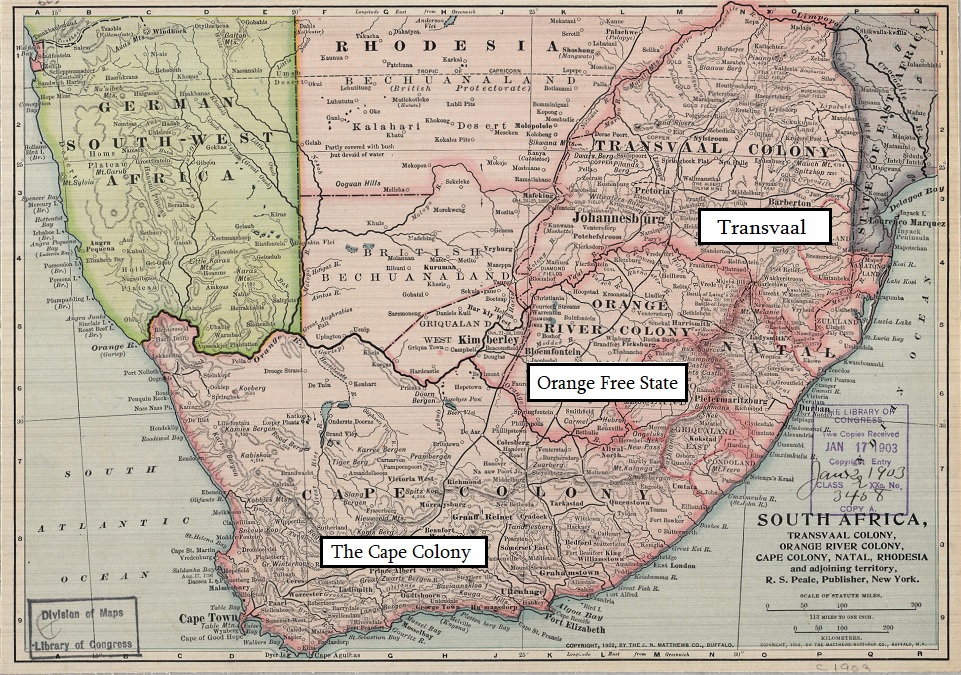

Nevertheless, with so much gold came more Uitlanders – ambitious individuals as well as foreign companies with the resources and know-how to manage difficult extraction. The Transvaal government made it difficult for newcomers to vote or otherwise fully participate in society, which didn’t bother those only interested in quick profits but antagonized the British to their ideological cores.

Nevertheless, with so much gold came more Uitlanders – ambitious individuals as well as foreign companies with the resources and know-how to manage difficult extraction. The Transvaal government made it difficult for newcomers to vote or otherwise fully participate in society, which didn’t bother those only interested in quick profits but antagonized the British to their ideological cores. The Jameson Raid reinforced to the Boer the importance of sticking together – supporting one another while constraining the Uitlanders. Tensions continued to build for several more years and eventually the British resorted to a more traditional approach and began building up troops along the border. In October of 1899, President Paul Kruger issued an ultimatum demanding they withdraw.

The Jameson Raid reinforced to the Boer the importance of sticking together – supporting one another while constraining the Uitlanders. Tensions continued to build for several more years and eventually the British resorted to a more traditional approach and began building up troops along the border. In October of 1899, President Paul Kruger issued an ultimatum demanding they withdraw. By the end of 1900, the British controlled most Boer territory and officially annexed both Transvaal and the Orange Free State. This should have been the end of hostilities, but many Boers still refused to surrender. Thus began a new phase of the war – two years of guerilla warfare and raids. The Afrikaners vandalized railroads, cut telegraph lines, and otherwise harassed British forces endlessly. They struck and then vanished, never allowing their opponents security or peace, but avoiding open conflict whenever possible.

By the end of 1900, the British controlled most Boer territory and officially annexed both Transvaal and the Orange Free State. This should have been the end of hostilities, but many Boers still refused to surrender. Thus began a new phase of the war – two years of guerilla warfare and raids. The Afrikaners vandalized railroads, cut telegraph lines, and otherwise harassed British forces endlessly. They struck and then vanished, never allowing their opponents security or peace, but avoiding open conflict whenever possible.  The Anglo’s perceived brutality severely damaged their standing in the eyes of the rest of the world as well as provoking outrage and protests back home. The war became increasingly unpopular as it continued to drag on, prompting the British to offer increasingly generous terms to the guerillas. Those determined to fight to the bitter end became known as Bittereinders (I’m not even making that up), while those who accepted reconciliation were labeled Hensoppers – literally, “hands-uppers.”

The Anglo’s perceived brutality severely damaged their standing in the eyes of the rest of the world as well as provoking outrage and protests back home. The war became increasingly unpopular as it continued to drag on, prompting the British to offer increasingly generous terms to the guerillas. Those determined to fight to the bitter end became known as Bittereinders (I’m not even making that up), while those who accepted reconciliation were labeled Hensoppers – literally, “hands-uppers.”

By the early 1850s, these voortrekkers, or “pathfinders” (yet another name for essentially the same folks), established two independent republics in southeastern Africa – The Transvaal (aka “The South African Republic”) and the Orange Free State (arguably the coolest name ever for a real place). There, the Boers continued their near-subsistence lifestyle with minimal actual government. The republics were initially recognized by the British, and soon instituted apartheid – strict segregation and discrimination, enforced by law as well as social custom. Apartheid would, of course, play a major role in South African history for the next 150 years, eventually earning international criticism before being reversed in the modern era. On a more positive note, it gave Bono and U2 something to talk about in the 1980s which the rest of us had actually heard of.

By the early 1850s, these voortrekkers, or “pathfinders” (yet another name for essentially the same folks), established two independent republics in southeastern Africa – The Transvaal (aka “The South African Republic”) and the Orange Free State (arguably the coolest name ever for a real place). There, the Boers continued their near-subsistence lifestyle with minimal actual government. The republics were initially recognized by the British, and soon instituted apartheid – strict segregation and discrimination, enforced by law as well as social custom. Apartheid would, of course, play a major role in South African history for the next 150 years, eventually earning international criticism before being reversed in the modern era. On a more positive note, it gave Bono and U2 something to talk about in the 1980s which the rest of us had actually heard of. Most of us have at least a working familiarity with the story of Joan of Arc. A simple (but not impoverished) French peasant girl, she began hearing voices from God telling her she was going to save France from the English and their Burgundian allies. Through some combination of cleverness, sincerity, and miraculous signs, she convinced Charles VII to let her lead French soldiers in battle and eventually secured his coronation.

Most of us have at least a working familiarity with the story of Joan of Arc. A simple (but not impoverished) French peasant girl, she began hearing voices from God telling her she was going to save France from the English and their Burgundian allies. Through some combination of cleverness, sincerity, and miraculous signs, she convinced Charles VII to let her lead French soldiers in battle and eventually secured his coronation. Even in a charade of a trial, participants generally strive to persuade themselves before seeking to persuade others. Humans are corrupt and selfish, to be sure – but most of us still want to be able to sleep at night. We like to win, but we don’t like to feel like horrible people while doing it. We demand a narrative – however twisted or internal – which justifies our treatment of others. We want to feel right.

Even in a charade of a trial, participants generally strive to persuade themselves before seeking to persuade others. Humans are corrupt and selfish, to be sure – but most of us still want to be able to sleep at night. We like to win, but we don’t like to feel like horrible people while doing it. We demand a narrative – however twisted or internal – which justifies our treatment of others. We want to feel right.  Thus, in the end, there were really only two points on which Cauchon and his cohorts found traction, even by their own standards.

Thus, in the end, there were really only two points on which Cauchon and his cohorts found traction, even by their own standards. Trial transcripts record repeated questioning of Joan concerning her attire. She expressed complete willingness to change into a dress once moved to a church prison, where she’d be guarded by women, as church law required. Her request was, each time, denied. Joan was asked to recite the Lord’s Prayer (something a witch would be unable to do). Again she was compliant, if only she were first given the opportunity for a proper confession. Impossible, unless she changed her outfit! And the cycle began anew.

Trial transcripts record repeated questioning of Joan concerning her attire. She expressed complete willingness to change into a dress once moved to a church prison, where she’d be guarded by women, as church law required. Her request was, each time, denied. Joan was asked to recite the Lord’s Prayer (something a witch would be unable to do). Again she was compliant, if only she were first given the opportunity for a proper confession. Impossible, unless she changed her outfit! And the cycle began anew.