Stuff You Don’t Really Want To Know (But For Some Reason Have To) About the Swahili Coast

Three Big Things:

1. The Swahili Coast was an important part of the Indian Ocean Trade Network in the 12th – 15th centuries. It’s a useful historical example of trade networks, cultural diffusion, and interaction between man and environment.

2. Over time, the people of the Swahili Coast evolved into a series of independent city-states sharing a common language (Swahili), a common faith (Islam), and a coherent economic system (er… “Trade”) – all of which were adapted and substantially modified to fit their local needs and collective culture.

3. The Swahili Coast declined after the Portuguese tried to take over Indian Ocean trade and mandate adherance to their superior Euopean whims. It didn’t work, but it did enough damage that the glory days were no more.

Introduction

The Swahili Coast was not a nation or political body in and of itself so much as a related series of trading posts, many of which developed into city-states, up and down the eastern coast of Africa. Unless otherwise specified, the term generally refers to the region during its economic and cultural zenith, from roughly the 12th century to just past the 15th. The Swahili Coast was in some ways a libertarian ideal – a loose but successful association of traders, held together not by a central government or national laws but connected through commerce and mutually beneficial norms which developed more or less organically over the years.

The term “Swahili” is not a designation of race, nationality, or religion, but a description of a specific group of people in a particular place and the language which evolved among them. It’s derived from the Arabic word for “coast” and is often translated as “people of the coast.” “Swahili” refers to both the people and their language – a lingua franca derived from Bantu (an indigenous language family from northern Africa) stirred together with healthy dollops of Arabic, Persian, and a sprinkle or two of whatever else was on hand.

Swahili language and culture evolved as part of a gradual migration to the coast from northern Africa. They were traders from the start, exchanging coastal items like shells and jewelry for agricultural products from the interior. They eventually settled in dozens of distinct communities up and down the coast, many of which became autonomous city-states and grew quite wealthy over time – especially after they began trading with merchants from the Indian Ocean as well as the continent itself.

The Power of Trade

When the Swahili Coast comes up in history class, it’s usually in the context of its role as a “trading network.” Rather than a formal arrangement between nations, trading networks are better understood as a series of regular stops along well-traveled routes. Sometimes stationary marketplaces would evolve along the route; other times traders would simply visit specific merchants or connect with other traders as possible. Like the famous “Silk Road,” what may appear on the map to be a baffling trek across multiple continents more often represented the cumulative effect of hundreds of shorter journeys, back and forth over some segment of the larger network. Long annual journeys were more common sailing along the Swahili Coast than hoofing the mountains and nether regions of the Middle and Far East, but that doesn’t mean every trader hit every post in order before reaching the end and starting back the other way.

Each transaction meant someone had to make a profit. The party who didn’t hoped to quickly sell their purchases at a slight markup themselves. Multiply this by a half-dozen or more exchanges before reaching the final buyer. That’s why for so many years, the majority of things being carted around the known world were “luxury goods” – silk, ivory, porcelain, spices, etc. Traders could only transport so much stuff, and they naturally chose items which were relatively easy to carry and on which a reliable profit could be made, no matter how many times it changed hands.

There was no specific point at which uncoordinated migration eastward suddenly became the “Swahili Coast.” No Grand Opening celebrations marked its connection to previously established trade networks or their role in the onset of the modern world. It evolved over several centuries – no doubt in innumerable fits and starts. Historians have to place it somewhere in history, however, and traditionally that means the “people of the coast” came into their own just as Europe was coming out of the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance. And, since history is about asking the “why” as much as sharing the “what,” there are several generally agreed-upon reasons for this emergence of the Swahili Coast into the larger narrative of world history.

Technology and Innovation

The development (or at least the substantial improvement) of dhows and other sailing vessels were making maritime travel and trade safer and easier, even over great distances. There are several things which make a dhow a dhow, but the two most likely to come up on your standard world history exam are how they were held together and what made them go. First, they were stitched together rather than simply glued or nailed. They were made of wood bound together with various types of cords and fibers. Second, and more noticeably, they had lateen sails. These triangular sails are still in use today, and when properly manipulated allowed boats to effectively sail against the wind – an obvious game-changer, nautically speaking, and a nice metaphor for technology in general.

The development (or at least the substantial improvement) of dhows and other sailing vessels were making maritime travel and trade safer and easier, even over great distances. There are several things which make a dhow a dhow, but the two most likely to come up on your standard world history exam are how they were held together and what made them go. First, they were stitched together rather than simply glued or nailed. They were made of wood bound together with various types of cords and fibers. Second, and more noticeably, they had lateen sails. These triangular sails are still in use today, and when properly manipulated allowed boats to effectively sail against the wind – an obvious game-changer, nautically speaking, and a nice metaphor for technology in general.

Dhows had existed in various forms since the Greeks and Romans (although some historians are convinced the Chinese invented them like they did everything else at some point). The important thing to the Swahili Coast, however, was that by the 1500s, Arab sailors had mastered the craft. Even Europe was beginning to catch on and develop its own versions of the technology – “cultural diffusion” in action. Dhows traditionally had one or two sails, but by the 15th century ships were getting substantially larger and able to withstand longer and more onerous journeys. It’s no coincidence that it was around this same time Christopher Columbus was able to reach the “New World” – boats could do that now.

The compass was coming into more popular use as well, again largely thanks to the Islamic world. Yes, the Chinese had invented long before, but like Toto’s “Africa,” ideas sometimes arrive, then fade, before coming back again, bigger and stronger and covered by Weezer.

Another old technology reappearing in new and improved form was the astrolabe, a device so modernized by Muslim astronomers and mathematicians as to be essentially a whole new toy. The astrolabe was a miraculous little device that allowed mere mortals to use the positions of the stars and calculations of various angles to determine the time, their current location, and accurately predict America’s Next Top Model, all from the deck of a sailing vessel in the middle of nowhere. Among other things, the astrolabe allowed Muslim sailors to determine the direction of Mecca from anywhere they happened to be, a major assist in adhering to their religious commitments. It was also, no doubt, a powerful psychological connection to home, allowing users to journey an infinite distance while in some way remaining connected to all they held dear. It wasn’t quite Google Hangouts, but it was leaps and bounds ahead of “maybe my next letter will arrive within the year.”

Another old technology reappearing in new and improved form was the astrolabe, a device so modernized by Muslim astronomers and mathematicians as to be essentially a whole new toy. The astrolabe was a miraculous little device that allowed mere mortals to use the positions of the stars and calculations of various angles to determine the time, their current location, and accurately predict America’s Next Top Model, all from the deck of a sailing vessel in the middle of nowhere. Among other things, the astrolabe allowed Muslim sailors to determine the direction of Mecca from anywhere they happened to be, a major assist in adhering to their religious commitments. It was also, no doubt, a powerful psychological connection to home, allowing users to journey an infinite distance while in some way remaining connected to all they held dear. It wasn’t quite Google Hangouts, but it was leaps and bounds ahead of “maybe my next letter will arrive within the year.”

Environmental and Geographic Conditions

Egypt (up the coast, at the other end of the Red Sea) had been the site of one of mankind’s founding civilizations, largely because the Nile flooded and receded with such wonderful predictability. To Egypt’s east, past the Persian Gulf and south a bit, the Indus River Valley (Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, etc.) soon followed, largely thanks to the monsoon winds which blew north-northeast (roughly Madagascar to India) every summer and south-southwest (back towards Madagascar) every winter. These same winds were still blowing thousands of years later and made sailing up and down the eastern coast of Africa a breeze. Literally.

Running an assist for the monsoon winds were natural reef barriers and coastal islands which shielded much of the Swahili Coast from the worst seasonal weather and allowed vessels relative safety when operating close to the shoreline. If you zoom in on a map of Africa’s eastern half, you’ll also notice numerous natural harbors which made it much easier for even large ships to dock safely. It’s nice when nature’s all cooperative like that.

Natural Resources

Even before the Indian Ocean developed into one of history’s major trade networks, the migrant Africans who became “people of the coast” were aided by regular rains and plentiful seafood. The interior of Africa provided for the rest of their needs, and as it turned out, offered plenty of goodies desired by the rest of the known world at the time as well. Swahili traders allowed goods to move both directions, with the traders and local rulers of Swahili city-states profiting both ways.

From the interior of Africa came ivory, gold, copper, various woods, incense, spices, tortoise shells, animal skins, etc. There was an early version of the slave trade emanating from Africa long before the discovery of the New World and the large-scale plantation version familiar to most students. This slave trade was later dwarfed by the extent to which Europe took the idea and ran with it, but at the time it was nevertheless significant. Popular imports into Africa from the Indian Ocean included glassware and pottery, jewelry, paper, paints, books, gunpowder, pointy weapons, silk, and other precious fabrics – the same things everyone else who could afford them wanted to buy.

Trading Partners

It doesn’t much matter what goods you have to trade or how efficiently you’re able to transport them if you don’t have people to trade with. As with most things throughout history, the Swahili Coast did not develop in isolation. Traders from the Arabic world, parts of Europe, and beyond, interacted with the Swahili regularly and at times intimately. It was not unusual for traders to stay in local Swahili homes while waiting for the proper winds to take them on their way, often for weeks or even months. The cultural and other exchanges made possible by such extended time together exceeded even those facilitated by trade. It didn’t hurt when they’d occasionally marry or otherwise choose to mingle genetic codes.

It doesn’t much matter what goods you have to trade or how efficiently you’re able to transport them if you don’t have people to trade with. As with most things throughout history, the Swahili Coast did not develop in isolation. Traders from the Arabic world, parts of Europe, and beyond, interacted with the Swahili regularly and at times intimately. It was not unusual for traders to stay in local Swahili homes while waiting for the proper winds to take them on their way, often for weeks or even months. The cultural and other exchanges made possible by such extended time together exceeded even those facilitated by trade. It didn’t hurt when they’d occasionally marry or otherwise choose to mingle genetic codes.

Barter remained common throughout the active life of the Swahili Coast, but several participating city-states developed their own coinage as well. Other currencies were often accepted, depending on what was considered economically viable at the time. Even cowrie shells could be used, like bottle caps in the post-Apocalyptic Fallout video games, or paper money in the modern United States, currency can be entirely symbolic and still quite effective as long as those exchanging it more-or-less agree on its value. Shared economic logistics, however flexible, were essential for trade to flourish. Without them, we’re not studying the Swahili Coast five centuries later.

The Syncretic Coast

It’s worth noting that no one element specifically caused or resulted from the others. The technology enabled the trade, sure – but the trade also pushed forward the technology. The city-states were possible because of environmental conditions and flourished because of trade, but trade flourished largely because there were city-states there, made possible by the natural environment, which in turn was forever changed by the development of city-states and trade. Once the various exchanges begin, it’s difficult to separate the fudge from the ice cream from the peanut butter from the sprinkles. But then, who would want to?

The Swahili Coast provides a wonderful example of not only linguistic evolution but cultural diffusion in general. Traditional African cultures (plural) eventually encountered Muslim traders (and maybe a few Sufis) and meshed to create a uniquely African form of Islam. As traders from the Arabic world and parts of Europe or the East continued to interact up and down the coast, languages were mingled, but so were technologies, cultures, diseases, economics, and genetics (because sailors get lonely). Over time, something unique and new was born, while each of its constituent elements remained somehow familiar, even traditional.

By their heyday in the 12th – 15th centuries, the Swahili Coast was almost universally Islamic, although in many cases they retained elements of native religions as well (particularly when it came to appeasing spirits who brought on illnesses or personal misfortunes or various forms of ancestor worship). They built mosques, but with architectural features unique to the Swahili. This sense of spiritual community (of “ummah”) further strengthened the informal unity of the Swahili Coast and helped guide how business was conducted.

The typical Swahili city-state had some form of sultan, a Muslim sovereign who shared in the profits and acted as “head of state” when needed, although it’s uncertain just how much power sultans actually held in contrast to local merchants. The available evidence suggests that wealthy merchants acted as advisors to the sultan and held other government offices, which would indicate that while local government may have regulated trade, trade in turn regulated local government. Swahili sultanates were thus economic offices as much as a political positions. Given the lack of clear lines between the secular and the supernatural in Islamic tradition, the sultan most likely held religious authority as well. The realities of the Swahili Coast meant none of these roles worked quite like they did anywhere else. Instead, they borrowed what they needed from those around them, mixed it with the parts they retained from their own forebears, and made it work for them. Syncretism at its finest.

Decline of the Swahili Coast

Most history students vaguely remember Vasco de Gama. He was the Portuguese explorer who eventually managed to round the southern tip of Africa and sail up to India via the Indian Ocean. Only a few years after Columbus thought he’d reached it by going west (Columbus never accepted that he’d run into a completely different continent), de Gama actually connected Europe with Asia via water, allowing trade and periodic conquest on a scale never before possible.

Most history students vaguely remember Vasco de Gama. He was the Portuguese explorer who eventually managed to round the southern tip of Africa and sail up to India via the Indian Ocean. Only a few years after Columbus thought he’d reached it by going west (Columbus never accepted that he’d run into a completely different continent), de Gama actually connected Europe with Asia via water, allowing trade and periodic conquest on a scale never before possible.

Unfortunately, like most European powers at the time (and the Portuguese were one of the biggies), the Portuguese approach to Indian Ocean trade was the same as their approach to pretty much everything else. Take it over, destroy anything or anyone not useful or sufficiently servile, and when it’s all broken, exhausted, and useless, thank God for the glorious harvest and move on. (Hence the glaring lack of idioms like “as subtle as the Portuguese” or “thinking long-term like a European.”) They weren’t able to actually subdue the Swahili or the Indian Ocean, but they did muck things up enough that it was never quite the same.

A few centuries later, eastern Africa was caught up in the slave trade on a much larger scale. Eventually it was divvied up with the rest of the continent as part of the “Scramble for Africa” in the 19th century. Swahili traders were still involved here and there, but never again as the autonomous and interesting players they’d been.

As I write this, the nation is getting restless with all of this Covid-19 “shelter in place” stuff. The daily body count is a constant feature on any 24/7 news channel, and there are some real concerns about how we survive economically even if most of us eventually get through it medically. I’m not going to argue the science, the economics, or even the politics of the thing at the moment. I can’t help noticing, however, several features of the current crisis which aren’t entirely unfamiliar to educators. Since many of us have a bit more time on our hands than we’d like, I figure there’s nothing lost in pondering a few of them here.

As I write this, the nation is getting restless with all of this Covid-19 “shelter in place” stuff. The daily body count is a constant feature on any 24/7 news channel, and there are some real concerns about how we survive economically even if most of us eventually get through it medically. I’m not going to argue the science, the economics, or even the politics of the thing at the moment. I can’t help noticing, however, several features of the current crisis which aren’t entirely unfamiliar to educators. Since many of us have a bit more time on our hands than we’d like, I figure there’s nothing lost in pondering a few of them here. Second: A Federalism of Convenience

Second: A Federalism of Convenience In theory, I’m in charge of my class. There are guidelines within which I’m expected to work – I can’t hit the kids, cuss at them, take their personal stuff, etc. There are rules limiting what I can and cannot do. Within those rules, however, I have some leeway how I manage my classroom. In theory, if I insist there be no talking during silent reading, then there should be no talking. If I decree a seating chart, students should sit where the chart says they sit. Because those are the rules. While they may be inconvenient for the individual, they’re good for the class as a whole – or at least that’s the ideal.

In theory, I’m in charge of my class. There are guidelines within which I’m expected to work – I can’t hit the kids, cuss at them, take their personal stuff, etc. There are rules limiting what I can and cannot do. Within those rules, however, I have some leeway how I manage my classroom. In theory, if I insist there be no talking during silent reading, then there should be no talking. If I decree a seating chart, students should sit where the chart says they sit. Because those are the rules. While they may be inconvenient for the individual, they’re good for the class as a whole – or at least that’s the ideal. Relationships are far more subtle. Many non-educators assume teachers get to know our kids because we’re all touchy-feely little snowflake-builders who just want everyone to feel loved. Sure, most of us care what happens to our kids, but that’s not the underlying reason relationships are essential. Without relationships, the only thing I’ve got to motivate them to cooperate are rules and reason. I don’t know if you’ve met an American teenager lately, but they’re not all fond of rules, and as a culture we’re not so great with “reason.”

Relationships are far more subtle. Many non-educators assume teachers get to know our kids because we’re all touchy-feely little snowflake-builders who just want everyone to feel loved. Sure, most of us care what happens to our kids, but that’s not the underlying reason relationships are essential. Without relationships, the only thing I’ve got to motivate them to cooperate are rules and reason. I don’t know if you’ve met an American teenager lately, but they’re not all fond of rules, and as a culture we’re not so great with “reason.” This is the part presenting the biggest challenge to local authorities at the moment as they try to figure out how long to keep some things closed, or – like the poor Governor of Michigan – how to let you go to Wal-Mart for car parts and milk but make sure you don’t grab a few $5 DVDs while you’re there because those aren’t “essential.”

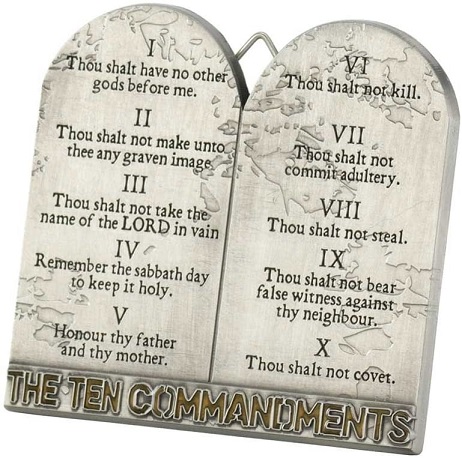

This is the part presenting the biggest challenge to local authorities at the moment as they try to figure out how long to keep some things closed, or – like the poor Governor of Michigan – how to let you go to Wal-Mart for car parts and milk but make sure you don’t grab a few $5 DVDs while you’re there because those aren’t “essential.” The Supreme Court’s decision in Stone v. Graham was announced on November 17th, 1980. Less than two weeks earlier, Ronald Reagan had been elected President of the United States, initiating what would later be called the “Reagan Revolution” – a resurgence of conservative values and policies anchored in an idealized past. The events leading to Stone began years earlier, but its outcome sent a message to the faithful in the 1980s similar to that of Engel v. Vitale and Abington v. Schempp two decades before: American’s fundamental values (meaning public promotion of Christianity) were under attack by intellectual elitists… aka “liberals.” And some of them wore robes.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Stone v. Graham was announced on November 17th, 1980. Less than two weeks earlier, Ronald Reagan had been elected President of the United States, initiating what would later be called the “Reagan Revolution” – a resurgence of conservative values and policies anchored in an idealized past. The events leading to Stone began years earlier, but its outcome sent a message to the faithful in the 1980s similar to that of Engel v. Vitale and Abington v. Schempp two decades before: American’s fundamental values (meaning public promotion of Christianity) were under attack by intellectual elitists… aka “liberals.” And some of them wore robes.

My students are not typical of those I’ve had in the past. I’ve had plenty of diversity in my 22+ years of public education, but it’s always been just that – diversity. My current school is not particularly diverse. Sure, there’s a mix of haggard white kids and not-particularly-prosperous Hispanic students walking the halls, but by far the greatest majority of my darlings are poor, Black, and from backgrounds the rest of us might cautiously clump together as “complicated.”

My students are not typical of those I’ve had in the past. I’ve had plenty of diversity in my 22+ years of public education, but it’s always been just that – diversity. My current school is not particularly diverse. Sure, there’s a mix of haggard white kids and not-particularly-prosperous Hispanic students walking the halls, but by far the greatest majority of my darlings are poor, Black, and from backgrounds the rest of us might cautiously clump together as “complicated.” For those of you new to education, there are several things you can bring up in any gathering of teachers to virtually GUARANTEE a complete and total breakdown of whatever was SUPPOSED to be happening. “So… what’s our primary goal as educators, exactly?” is a classic – both unanswerable and constantly answered poorly. “How should our honors/advanced/GT/AP classes be different than our regular/on-level/academic classes?” is another sure-fire disrupter. Oh, and I particularly enjoy overtly ethical and unavoidably emotional conundrums: “Do we really want students missing class because they’re not properly aligned with our outdated and possibly misogynistic ideas about clothing?” or “Should attendance really matter if they can demonstrate they can do the work and have mastered the skills?”

For those of you new to education, there are several things you can bring up in any gathering of teachers to virtually GUARANTEE a complete and total breakdown of whatever was SUPPOSED to be happening. “So… what’s our primary goal as educators, exactly?” is a classic – both unanswerable and constantly answered poorly. “How should our honors/advanced/GT/AP classes be different than our regular/on-level/academic classes?” is another sure-fire disrupter. Oh, and I particularly enjoy overtly ethical and unavoidably emotional conundrums: “Do we really want students missing class because they’re not properly aligned with our outdated and possibly misogynistic ideas about clothing?” or “Should attendance really matter if they can demonstrate they can do the work and have mastered the skills?” The primary criticism of the Five Paragraph Essay is that it’s stifling. Students learn to plug-n-play to fit a format without any real conviction and little actual learning. It’s barely an evolutionary step up from fill-in-the-blank worksheets. Secondary teachers and college professors alike lament their students’ inability to break free once their minds have been trapped and corrupted by this five-part infection.

The primary criticism of the Five Paragraph Essay is that it’s stifling. Students learn to plug-n-play to fit a format without any real conviction and little actual learning. It’s barely an evolutionary step up from fill-in-the-blank worksheets. Secondary teachers and college professors alike lament their students’ inability to break free once their minds have been trapped and corrupted by this five-part infection. I’ve previously compared writing with structure to

I’ve previously compared writing with structure to  I don’t belong to a particularly organized English department. There’s no time built into the weekly (or yearly) schedule for collaboration or team-building or whatever, and as of March I don’t actually know the names of everyone who teaches the same subject I do. Meetings are infrequent and informal (although there were snacks last time), and most of the teachers I actually talk to regularly are a door or two in either direction in my hallway.

I don’t belong to a particularly organized English department. There’s no time built into the weekly (or yearly) schedule for collaboration or team-building or whatever, and as of March I don’t actually know the names of everyone who teaches the same subject I do. Meetings are infrequent and informal (although there were snacks last time), and most of the teachers I actually talk to regularly are a door or two in either direction in my hallway. Twenty years ago, I would have been intimidated by the terminology (the “scaffold,” not the “$#*&%”). I was getting by on enthusiasm and self-delusion and if I’d slowed down to think about anything too clearly, I’d have been Wile E. Coyote just after running off the cliff – he didn’t plummet until he looked down.

Twenty years ago, I would have been intimidated by the terminology (the “scaffold,” not the “$#*&%”). I was getting by on enthusiasm and self-delusion and if I’d slowed down to think about anything too clearly, I’d have been Wile E. Coyote just after running off the cliff – he didn’t plummet until he looked down.