The dilemma of any effort to compile “must know” Supreme Court cases is deciding where to draw the line. If you narrow it to a list of 12, there are at least 3 or 4 others that really MUST be added in the name of consistency. If you expand the list to, say… 24, you’re sacrificing another half-dozen that should simply NOT be neglected if you’re to retain ANY credibility.

The dilemma of any effort to compile “must know” Supreme Court cases is deciding where to draw the line. If you narrow it to a list of 12, there are at least 3 or 4 others that really MUST be added in the name of consistency. If you expand the list to, say… 24, you’re sacrificing another half-dozen that should simply NOT be neglected if you’re to retain ANY credibility.

Then there’s the actual summarizing. How much background really matters to the casual reader or panicked student? Is it enough to say that the Dred Scott decision declared that slaves weren’t people and Congress couldn’t limit slavery in the territories, or is it necessary to explain how this helped lead to the Civil War? What about the individuals involved and their stories? Even notoriously bad Supreme Court decisions are built around real situations, the details of which matter very much to the outcome. Besides, decisions (good or bad) mean nothing out of their historical context, do they?

It’s in that spirit I’ve decided to add a dozen or so cases to my ongoing effort to publish my own compilation of accessible, enlightening, brilliantly witty summaries of the “Landmark Supreme Court Cases” every American should know and every worried student can reference before the AP Exam or Semester Test. Rather than duplicate my approach with the current fifteen or so, these additions will be one-page summaries hitting the highlights of each case along with a brief excerpt from the Court’s majority opinion.

In my draft, I’m calling these “Worth A Look.” Because they’re, well… you know.

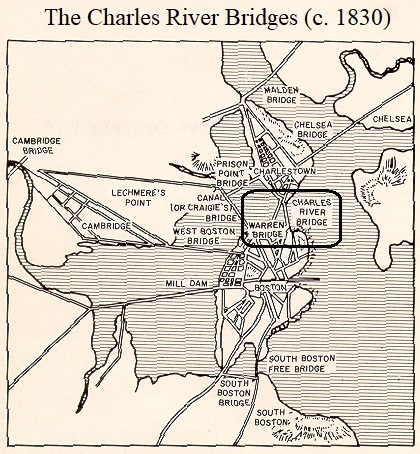

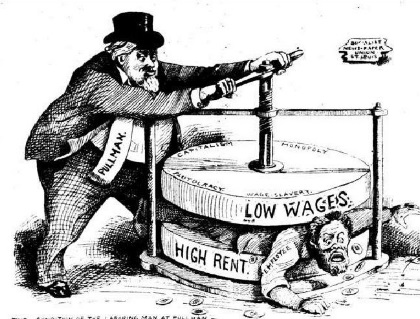

The two cases below occurred forty years apart and involved very different circumstances. In Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge (1837), the issue was whether or not Massachusetts owed it to a company with whom they’d done business to stick to the implied terms of their original contract. In Munn v. Illinois (1877), the question was whether or not the state could regulate private business in the name of public good. Both, however, dealt with the question of property rights and individual autonomy vs. the social contract – what was good for society as a whole. It’s that aspect I find most interesting, and most relevant all these years later.

Worth A Look: Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge (1837)

{W}hat is a monopoly, but a bad name, given to anything for a bad purpose? Such, certainly, has been the use of the word in its application to this case… A monopoly, then, is an exclusive privilege conferred on one, or a company, to trade or traffick in some particular article; such as buying and selling sugar or coffee, or cotton, in derogation of a common right. Every man has a natural right to buy and sell these articles; but when this right, which is common to all, is conferred on one, it is a monopoly, and as such, is justly odious. It is, then, something carved out of the common possession and enjoyment of all, and equally belonging to all, and given exclusively to one.

But the grant of a franchise is not a monopoly, for it is not part or parcel of a common right. No man has a right to build a bridge over a navigable river, or set up a ferry, without the authority of the state. All these franchises, whether public property or public rights, are the peculiar property of the state… and when they are granted to individuals or corporations, they are in no sense monopolies; because they are not in derogation of common right.

{from the Court’s Majority Opinion, by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney}

In 1785, the Massachusetts legislature worked out a deal with the Charles River Bridge Company (CRBC). In exchange for building and maintaining a bridge across the Charles River (connecting Boston and Cambridge), the company would have the right to collect tolls from those traveling over the bridge. The bridge was built and the company because quite wealthy from the tolls, which they kept rather steep even long after their initial costs were recouped. Over time, as Massachusetts continued to grow, people grew rather annoyed with the high tolls and demanded their elected representatives do something about it.

In 1828, the state legislature granted a new charter to the Warren River Bridge Company (WRBC), who built a second bridge not all that far from the first. This bridge, however, was to be toll-free once initial costs were recovered and a reasonable profit earned for the company. Not surprisingly, people liked this bridge much better. The Charles River Bridge Company sued in state court, claiming the new charter violated their property rights and represented a broken contract by the State of Massachusetts. Not only was this very naughty, they argued, but it violated Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution, which says (among other things) that “no state shall… pass any… law impairing the obligation of contracts…”

In 1828, the state legislature granted a new charter to the Warren River Bridge Company (WRBC), who built a second bridge not all that far from the first. This bridge, however, was to be toll-free once initial costs were recovered and a reasonable profit earned for the company. Not surprisingly, people liked this bridge much better. The Charles River Bridge Company sued in state court, claiming the new charter violated their property rights and represented a broken contract by the State of Massachusetts. Not only was this very naughty, they argued, but it violated Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution, which says (among other things) that “no state shall… pass any… law impairing the obligation of contracts…”

The case worked its way to the Supreme Court, which found that Massachusetts had neither broken their original contract with CRBC nor violated the “contract clause” of the Constitution. While the original contract with CRBC may have been reasonably understood to suggest monopoly rights for the life of the company or the bridge, the contract never actually stated that, so… oops.

The Charles River decision was important for several reasons beyond “read the small print before you sign.” It was an early demonstration of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s desire to pull back from the passionate nationalism of his predecessor, John Marshall. Taney was a big believer in States’ Rights, which would shape a generation of Supreme Court decisions in various ways – most infamously in the Dred Scott decision authored by Taney in 1857.

Charles River also reflected a concern with the “general welfare” of both society and the economy. The perceived exploitation by CRBC as they refused to back down on their rates or otherwise compromise for the good of the collective meant they were standing in the way of prosperity. What if steamboat operators who’d received exclusive rights up and down the river took a similar approach and decided that competition from railroads violated the spirit of that agreement? Should perceived property rights be allowed to hold back society’s progress indefinitely?

States can limit or modify what’s acceptable even in contracts between private citizens or organizations as long as such interference is tempered with reason and done in the name of appropriate state “police powers.” They also have great latitude to serve the “general welfare” of their citizens. That didn’t start with Charles River, but the case certainly helped clarify and strengthen those roles going forward.

Worth A Look: Munn v. Illinois (1877)

When one becomes a member of society, he necessarily parts with some rights or privileges which, as an individual not affected by his relations to others, he might retain. “A body politic,” as aptly defined in the preamble of the Constitution of Massachusetts, “is a social compact by which the whole people covenants with each citizen, and each citizen with the whole people, that all shall be governed by certain laws for the common good.”

This does not confer power upon the whole people to control rights which are purely and exclusively private… but it does authorize the establishment of laws requiring each citizen to so conduct himself, and so use his own property, as not unnecessarily to injure another. This is the very essence of government…

Under these powers, the government regulates the conduct of its citizens one towards another, and the manner in which each shall use his own property, when such regulation becomes necessary for the public good. In their exercise, it has been customary in England from time immemorial, and in this country from its first colonization, to regulate ferries, common carriers, hackmen, bakers, millers, wharfingers, innkeepers, &c., and, in so doing, to fix a maximum of charge to be made for services rendered, accommodations furnished, and articles sold. To this day, statutes are to be found in many of the States upon some or all these subjects; and we think it has never yet been successfully contended that such legislation came within any of the constitutional prohibitions against interference with private property…

{from the Court’s Majority Opinion, by Chief Justice Morrison R Waite}

Responding to pressure from the National Grange (a farmers’ cooperative often remembered simply as the “Grangers”), the state of Illinois passed legislation capping the amounts grain elevators and storage warehouses could charge. A Chicago warehouse run by Munn & Scott was caught overcharging and found guilty after a brief trial. They appealed, claiming that the state-imposed limits on their income was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment which says, in part, that no State may “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

The Supreme Court rejected this line of reasoning and validated the “Granger Laws” as entirely appropriate and constitutional. Since before the founding of the United States, Chief Justice Waite explained, the foundational purpose of enlightened government is to support and regulate the social contract – each citizen giving up a small bit of autonomy for the larger good. In the end, this benefits everyone, including those making these minor sacrifices.

The Supreme Court rejected this line of reasoning and validated the “Granger Laws” as entirely appropriate and constitutional. Since before the founding of the United States, Chief Justice Waite explained, the foundational purpose of enlightened government is to support and regulate the social contract – each citizen giving up a small bit of autonomy for the larger good. In the end, this benefits everyone, including those making these minor sacrifices.

The Court also noted that while the Commerce Clause (in Article I, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution) gives the federal legislature final power over interstate commerce, that doesn’t prevent states from reasonable regulation and oversight of the portion of that commerce taking place within their borders. The extent to which states could exercise this regulation and oversight was severely rolled back a decade later in Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific Railway Company v. Illinois (1886), after which Congress created the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate railroad and storage rates, and eventually a wide range of public utilities.

Munn established the validity of legislation regulating any industry or service determined to be essential to public interests. In the short term that primarily meant those related to farming and distribution of crops – meaning even the all-mighty railroads were impacted by the Court’s decision. While which products or services are considered essential to the public good have naturally evolved over the years, but the underlying principle has held ever since.

1. After it became clear that state-sponsored prayer was no longer a realistic option in public education, states began experimenting with the idea of a “moment of silence” during which students could pray (although no one had ever suggested that they couldn’t).

1. After it became clear that state-sponsored prayer was no longer a realistic option in public education, states began experimenting with the idea of a “moment of silence” during which students could pray (although no one had ever suggested that they couldn’t).

1. Responsible for the best-known and arguably most influential set of legal codes in the ancient world. Key issue: they were written down and publicly posted.

1. Responsible for the best-known and arguably most influential set of legal codes in the ancient world. Key issue: they were written down and publicly posted. Hammurabi was the sixth king of Babylon, having assumed the throne from his unfortunately-named father, Sin-Muballit. They seem to have been Amorites, originally a tribe from western Syria and one of the groups most often mentioned in the Old Testament as both scary and deserving of slaughter whenever possible. Then again, records from this time period are fragmentary and the language maddeningly inconsistent, so a term like “Amorite” may have been more of a title or categorization than a specific ethnic group or family name. Like much from this era, the issue is cloaked in contradictory evidence and academic debate.

Hammurabi was the sixth king of Babylon, having assumed the throne from his unfortunately-named father, Sin-Muballit. They seem to have been Amorites, originally a tribe from western Syria and one of the groups most often mentioned in the Old Testament as both scary and deserving of slaughter whenever possible. Then again, records from this time period are fragmentary and the language maddeningly inconsistent, so a term like “Amorite” may have been more of a title or categorization than a specific ethnic group or family name. Like much from this era, the issue is cloaked in contradictory evidence and academic debate. Periodic cultural melodrama over this chronology stems from a popular, but false, dichotomy between inspiration and incorporation; there’s nothing particularly suspicious about legal codes sharing common elements or social norms evolving from existing customs. Such reasoning would defrock the most sanctified sermon or inspirational song upon discovering the use of standard rhetorical devices or popular chord changes.

Periodic cultural melodrama over this chronology stems from a popular, but false, dichotomy between inspiration and incorporation; there’s nothing particularly suspicious about legal codes sharing common elements or social norms evolving from existing customs. Such reasoning would defrock the most sanctified sermon or inspirational song upon discovering the use of standard rhetorical devices or popular chord changes.