It’s An Elephant, Dammit!

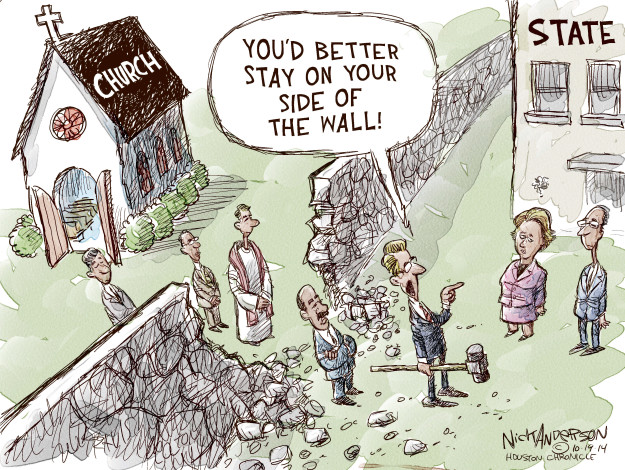

I’ve been researching and drafting what I hope will be the next “Have To” History book. The focus is on the tricky balance between “free exercise” and “establishment” in relation to public education – how to allow students (and to a lesser extent, educators) to express their sincerely held beliefs while still protecting the supposed neutrality of the system towards all things supernatural. It’s fascinating stuff (well, to me, at least), but I confess I’m having trouble with potential titles.

I’ve been researching and drafting what I hope will be the next “Have To” History book. The focus is on the tricky balance between “free exercise” and “establishment” in relation to public education – how to allow students (and to a lesser extent, educators) to express their sincerely held beliefs while still protecting the supposed neutrality of the system towards all things supernatural. It’s fascinating stuff (well, to me, at least), but I confess I’m having trouble with potential titles.

I was initially thinking “Have To” History: A Hall of Separation, but my wife assures me no one will know what I’m talking about (and she’s probably right). I’ve tried variations which are a bit more specific – “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation – Balancing Free Exercise and Non-Establishment in Public Education Throughout American History, for example. Unfortunately, paragraph-long book titles went out of fashion nearly a century ago. Plus, I’m not sure it would fit on the cover.

One of the most challenging aspects so far is deciding what to include. The Supreme Court has tackled a variety of issues involving the separation of church and state in relation to public schooling – school prayer (both teacher and student-led), teaching evolution, equitable facilities usage, and the real biggie these days – funding and resources. (These often involve “school choice” programs, vouchers, etc.) At the same time, education is historically a local concern, even in the 21st century. The Supremes generally prefer to restrict themselves to cases which involve either (a) substantial constitutional issue which must be addressed, or (b) issues which have presented themselves to various district courts and in which consistency has proven elusive.

All So Appealing

That means that many times, the most fascinating cases are those which never get past the nearest Court of Appeals. There are twelve of these scattered strategically across the U.S. and they’re a pretty big deal. Prayer on football fields, schemes for redirecting public money into select religious programs, challenges to curriculum – they get all kinds of fun stuff. The idea is that they use precedents set by the Supreme Court as their guide, along with the U.S. Constitution, of course.

But the devil, as they say, is in the details, and it’s not always obvious how existing decisions might shape each new variation. If it were, the case probably wouldn’t have made it that far. That’s the whole point of consistent national interpretation, after all.

It was at the Circuit Court level that I stumbled across Mozert v. Hawkins, which was decided by the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals (Cincinnati, OH) in 1987. Fascinated by the summary I was reading, I searched for more details and ended up – quite accidentally – stumbling through court records from several years earlier in the process. It was reading through these that I fell in love – with the case, with the process, with the various written opinions along the way, and with how very American it is from every angle.

Buckle up, because this one will take a while. Unlike the succinct, pithy, carefully balanced and academically maximized summaries in the book, this is what those cases look like in my brain before I get serious about making them, you know… useful.

Yes, Virginia – There ARE Two Clauses

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution opens with two clauses related to religion: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”

The first of these, commonly referred to as the “Establishment Clause,” prohibits Congress from doing anything to promote a particular religion or religion in general. The second, known as the “Free Exercise Clause,” says that Congress can’t do anything to discourage or inhibit religious beliefs of citizens. Over time, these limitations have been understood to apply to government at all levels.

Most “wall of separation” cases related to public education involve questions of “establishment.” When Ms. Magdalene puts up Christmas decorations in her classroom, that violates the Establishment Clause. Inviting local clergy to open graduation ceremonies with a brief prayer is a no-no because it’s “establishment.” Requiring equal time for Creationism when it’s time for the chapter on Evolution? You guessed it – that’s “establishment” as well.

From time to time, however, a case will work its way through the system asserting the opposite. In these “free exercise” cases, the claim is that the state – in this case, manifested as the public school system – has hindered personal expressions of religious belief or behavior without sufficient cause. The “sufficient cause” part is important because the state has the right to place some limits on how faith is manifested when there’s a good reason. (Human sacrifice, for example, is a “no-no” even if your gods demand placation.) Government entities must demonstrate that they have a good reason for their restrictions, however. And, if there are less-restrictive ways to accomplish those goals, they have to try those first.

The Problem With Fiction

Enter Vicki Frost, the mother of several children attending public school in Hawkins County, Tennessee. School had only been a session for a few weeks in the Fall of 1983 when her 6th grade daughter brought home an English textbook containing a story she’d been assigned to read. This story, as it turned out, involved… mental telepathy. Worse, this fictional telepathy was treated by the story as if it were no big deal, despite clearly being un-Biblical.

Enter Vicki Frost, the mother of several children attending public school in Hawkins County, Tennessee. School had only been a session for a few weeks in the Fall of 1983 when her 6th grade daughter brought home an English textbook containing a story she’d been assigned to read. This story, as it turned out, involved… mental telepathy. Worse, this fictional telepathy was treated by the story as if it were no big deal, despite clearly being un-Biblical.

As Ms. Frost perused her daughter’s textbook, she discovered a number of other alarming tales as well – stories normalizing cultural diversity, humanism, evolution, disobedience to parents, and the idea that children must eventually learn to think for themselves.

Frost spoke to some other concerned parents, and they approached the school about providing alternative reading assignments. At first, the school agreed. This meant, of course, that this handful of students had to be sent to the library or another room each time the class discussed the short stories in question. There could be no real collaboration or analysis unless teachers held a separate, alternative class for them each time. Eventually, the district mandated that all students would follow the prescribed curriculum. Refusal to do so would mean failing the class and could lead to disciplinary action as well.

Frost and friends took their school district to court. They claimed the district’s insistence on using this particular textbook was a violation of their “free exercise” of religion as parents. Because the issue was constitutional rather than criminal, it was heard in federal court (as opposed to the more familiar criminal courts we see in TV dramas). The lead plaintiff was another parent in the group, Bob Mozert – hence the official moniker of the case as it moved through the system.

It’s too bad, really – Frost v. Hawkins has a way more badass ring to it. Very Game of Thrones. But that’s paperwork for you.

Judge Hull

District Judge Thomas Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee (where the case presumably began) was not initially swayed by the parents’ complaints. He issued a summary judgement dismissing the case – meaning he didn’t find enough substance to their complaint to even hold a full trial. It’s sort of the judicial version of snorting and then asking, “Oh, were you serious?”

District Judge Thomas Hull of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee (where the case presumably began) was not initially swayed by the parents’ complaints. He issued a summary judgement dismissing the case – meaning he didn’t find enough substance to their complaint to even hold a full trial. It’s sort of the judicial version of snorting and then asking, “Oh, were you serious?”

Judge Hull’s written explanation contains some interesting details and introduces themes which – in retrospect – serve as something of an “overture” for the larger story of Mozert as it moved through the courts. He couldn’t have known this, of course, let alone anticipate that he was about to get his honorable hand slapped by the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals for dismissing these parents’ complaints so readily.

{The} allegation that the books in question teach that one does not need to believe in God in a specific way, but that any type of faith in the supernatural is an acceptable method of salvation, {constitutes a valid complaint} only if the books were asserting either that salvation, or some form of religion, was necessary, or that no religion was necessary. In other words, the test would be whether the books were neutral on the issue of religion, or violating this neutrality either by advocating a particular religion or by being anti-religion.

The plaintiffs were directed to specify to the Court exactly which parts of the books substantiated their allegation. They have now responded, and it is clear that the books neither instruct the children that they must be saved, nor that they do not need any form of religion. The plaintiffs do not suggest otherwise. What they object to is the underlying philosophy of the readers, taken as a whole, which is geared to making the school children better participants in the world community. The books are aimed at fostering a broad tolerance for all of man’s diversity, in his races, religions and cultures. They intentionally expose the readers to a variety of religious beliefs, without attempting to suggest that one is better than another.

In other words, the initial complaint that the textbook in question was unfair to their religion turned out to be in reality a complaint that the book was equally fair to all religions. This, the parents insisted, was diminishing towards the one true faith – theirs. They even provided examples of several particularly problematic passages, as Judge Hull explained:

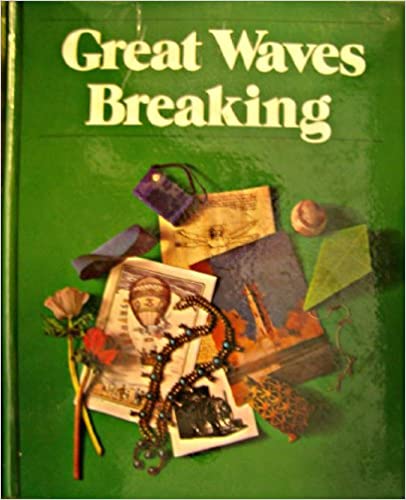

The first example is a poem entitled “The Blind Men and the Elephant” by John Godfrey Saxe, described as a Hindu fable… The poem described six blind men who each feel a portion of an elephant and reach a conclusion of what the whole must be like on the basis of their limited experience…

You all know this one. One man says, “an elephant is like a rope” and another, “it’s more like a solid wall” – that sort of thing. The lesson, of course, is that no one person usually has the complete picture or the whole truth.

In fairness to these clearly very fundamentalist parents, they’re not entirely wrong. The message that “all truths have roughly the same value” and “everyone has to find their own way” isn’t so far removed from “I am he as you are he as you are me and we are all together, goo goo ga-joo.” When the core of your faith is “I am THE Way, THE Truth and THE Life,” this sort of neo-hippie-unitarian nonsense is arguably chilling. And their argument wasn’t that each individual story was untenable, but that as a whole, the book seems to have made its choices in order to inculcate a specific set of values – inclusiveness, moral relativism, feminism, humanism, etc.

Next time you come across a literature textbook from the late 1970s, take a gander for yourself. My money says you’ll find touchy-feely neo-hippie. So they may have been onto something.

Did Soros Pay For This?

I’d respectfully suggest, however, that Frost and company made a major strategic error when they included their next example on the “naughty” list. Still quoting Judge Hull:

I’d respectfully suggest, however, that Frost and company made a major strategic error when they included their next example on the “naughty” list. Still quoting Judge Hull:

The second illustration… is from the classic story, The Diary of Anne Frank…

Whoa, there, my little inquisitors!

Let’s assume for a moment there are excerpts in Frank’s diary that proffer potentially problematic theology. The book isn’t necessarily above questioning just because she’s, you know… um…

But how was this a solid move strategically? How must THAT conversation have gone?

“Look guys, we dance along the rightmost edge of ultra-fundamentalism. Even other Christians find us a bit off-putting. But we might be able to get a win here if we can present our case as a reasonable effort to defend our sincerely-held beliefs. We’ve already got a few dozen examples on our list – stories with witchcraft, teen rebellion, eastern mysticism, and of course plenty of ‘one world order’ stuff. I’m not sure we’re doing enough, however, to demonize the most sympathetic figure of the 20th century. If only we could more strongly associate ourselves by implication with history’s single most horrifying example of intolerance and self-righteousness without the slightest awareness of irony…”

It just strikes me as slightly tone deaf is all.

This Court does not doubt the sincerity of the plaintiffs’ beliefs, nor does it doubt that the implication which can validly be found in the passages cited, offends the plaintiffs. This Court is satisfied by the examples filed that the books have the philosophical viewpoint plaintiff alleges. However, it cannot find in them, anything that can be considered a violation of plaintiff’s constitutional rights…

{T}he First Amendment “does not guarantee that nothing offensive to any religion will be taught in the schools.” (Williams v. Board of Education of the County of Kanawha, 4th Circuit Court of Appeals, 1975). What is guaranteed is that the state schools will be neutral on the subject, neither advocating a particular religious belief nor expressing hostility to any or all religions. From what this Court has read, it would appear that the Holt Basic Readings carefully adopt this constitutionally mandated neutrality. Moreover, they are well calculated to equip today’s children to face our increasingly complex and diverse society with sophistication and tolerance.

In short, Judge Hull fully accepted that the message to which these parents objected clearly emanated from the text when considered as a whole. This did not, however, constitute enough of a violation to justify forcing the school to change what they were doing. Efforts to equip students to function in a diverse world in which people hold all sorts of beliefs and practice any number of weird behaviors wasn’t a bug – it was a feature. The school wasn’t asking students to change what they believed or did, so it simply wasn’t a First Amendment Issue, according to Hull. In fact, it wasn’t even worth having a trial.

The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals wasn’t ready to say whether or not anyone’s “free exercise” was being infringed, but neither did they buy the quick-and-easy summary judgement of Judge Hull. That’s where Part Two of this wacky trilogy begins.

Well, my #11FF, I decided to record a few podcasts for new (or reviving) educators. This seems like a wonderful idea because I lack the proper equipment, there are dozens of excellent education podcasts out there already, I have nothing to sell, and this year is so weird it’s hard to know how to prepare for it anyway.

Well, my #11FF, I decided to record a few podcasts for new (or reviving) educators. This seems like a wonderful idea because I lack the proper equipment, there are dozens of excellent education podcasts out there already, I have nothing to sell, and this year is so weird it’s hard to know how to prepare for it anyway. In Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, Juliet laments that she cannot be with Romeo largely because of their last names. Their families are enemies and neither would ever accept the other into their homes. Standing on her balcony, unaware that he’s listening, she rejects the idea that names could be so important. Why should it matter what you’re called if you’re as awesome as Romeo – at least in Juliet’s eyes?

In Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet, Juliet laments that she cannot be with Romeo largely because of their last names. Their families are enemies and neither would ever accept the other into their homes. Standing on her balcony, unaware that he’s listening, she rejects the idea that names could be so important. Why should it matter what you’re called if you’re as awesome as Romeo – at least in Juliet’s eyes?

Finally, there’s an additional, somewhat awkward motivation as well. I’m an old white guy whose hearing isn’t what it used to be. I genuinely want to learn my students’ names and say them correctly, but there are more each year that I never seem to quite get comfortable with. At the same time, it feels more important than ever that I demonstrate at least that much attention and respect to those whose names are most likely to give me trouble. With this assigment, I’ll have a reference as often as I need it to exactly how they want their name pronounced – because they’re the ones saying it.

Finally, there’s an additional, somewhat awkward motivation as well. I’m an old white guy whose hearing isn’t what it used to be. I genuinely want to learn my students’ names and say them correctly, but there are more each year that I never seem to quite get comfortable with. At the same time, it feels more important than ever that I demonstrate at least that much attention and respect to those whose names are most likely to give me trouble. With this assigment, I’ll have a reference as often as I need it to exactly how they want their name pronounced – because they’re the ones saying it.

Don’t get excited – I’m not diving into current events or anything. (I’m

Don’t get excited – I’m not diving into current events or anything. (I’m

So how could we do this if we’re not in the same place?

So how could we do this if we’re not in the same place?

I like several things about this lesson in this format:

I like several things about this lesson in this format: There are, of course, several downsides:

There are, of course, several downsides: