It’s dangerous to start pushing a book when I haven’t seen the physical final product yet. I learned last time that no matter how many weird formatting issues, overlooked typos, and random nude shots you’re POSITIVE you’ve resolved, there are always a few more waiting to be discovered once you’ve started promoting the thing and your entire sense of self-worth is on the line.

It’s dangerous to start pushing a book when I haven’t seen the physical final product yet. I learned last time that no matter how many weird formatting issues, overlooked typos, and random nude shots you’re POSITIVE you’ve resolved, there are always a few more waiting to be discovered once you’ve started promoting the thing and your entire sense of self-worth is on the line.

And yet, I’m pretty happy this one is finally “live,” no matter what minor edits may be necessary down the road. I’m sharing the Author’s Intro with you here by way of a teaser so you’ll get SO intrigued and engaged that you simply have to know more, whatever the cost or personal risk involved. Besides, haul around a volume like this for a few days and everyone will assume you are a DEEP, DEEP THINKER. It’s THAT good.

“Have To” History: A Wall Of Education – What the Supreme Court Really Says (and What It Really Doesn’t) About the Separation of Church and State in Education

When I published “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases a few years ago, I added a brief “Afterword” explaining how I came to find myself so fascinated with the decisions of the nation’s highest court over the years and what I hoped to accomplish by doing my own overview of 45 or so of the most important cases one should know as a student, citizen, or wanna-be intellectual elitist. What I didn’t add is that the book I initially set out to write was this one. It was simply too big of a task at the time, besides which I couldn’t actually figure out if anyone would want to read it or not. (That’s not the only reason to write, of course, but it’s certainly a consideration – at least for me.)

So, I chose to instead focus on something that would easily serve a wide variety of readers wanting or needing to know more about multiple cases but lacking the time or motivation to get too academic about the whole thing. Presumably there are folks out there relieved to let me boil things down for them so they can get on with their lives.

This book is far less general. I’ve tried to summarize and contextualize the most important and interesting cases in the history of the Supreme Court related to church-state issues in education. It’s an endlessly complex and fascinating topic, and I’ve done my best to present each case fairly while retaining some of the passion I feel along the way. I won’t claim this is an entirely “balanced” treatment, but I’ve made every effort to be historically and intellectually honest within the limits of my own convictions (which will no doubt be easily discernible to attentive readers).

There are so many ways to approach almost any topic related to the Supreme Court or its cases. I’ve tried to avoid getting bogged down in procedural matters or terminology unless essential to a specific case. Similarly, I’ve shied away from extended explorations of originalism vs. the “living constitution” approach, judicial activism vs. judicial restraint, etc., although each will pop up in relation to specific cases or written opinions here and there. As a long-time history teacher, I’m a bit more susceptible to contextual rabbit holes, but I’ve tried to keep the focus narrow enough to remain useful for the average reader. Maybe even engaging.

The tricky thing about that, of course, is that the historical roots of the First Amendment and the twin religion clauses with which it begins are undeniably relevant to how they have been and should be understood and applied. As I once told students, there are two things we must always remember about the study of history. First, people throughout time and across the globe were in almost every important way just like us. Let’s not overly idealize, demonize, or otherwise mythologize them. Second, the lives and perceptions of people in other times and places throughout history were nothing like ours (in many important ways, at least). There’s no point claiming we can ever fully understand how they felt or why, or what they thought their words and actions truly meant.

Yes, these are essentially opposites. That doesn’t mean either one is incorrect.

Did our Founders and Framers believe in absolute separation of church and state? Not in the modern sense of the phrase, no – not most of them, anyway. For a full generation after the ratification of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights, the original states wrestled with how to best delineate an ideal relationship between church and state. Those pushing for less establishment (as understood at the time) largely did so out of the conviction that greater separation was best for true religion to flourish, and that only faith untainted by politics could provide the foundational morality essential for the republic to survive. Those favoring freer exercise of religion, or even various mechanisms allowing some state support of select institutions, wanted very much the same thing and for very similar reasons.

What most agreed on during debates over the Bill of Rights and throughout that first critical generation of new Americans was that religious division and strife were to be avoided – if not at all costs, then at something pretty close. Many recognized that they lived in an age of not only massive political revolution but of a potentially new approach to faith and humanity in general, and while it may not be clear what things should look like, they had plenty of examples of what hadn’t worked or wasn’t working. The age-old debate about original intent vs. changing circumstances is thus particularly problematic when it comes to church-state relations since it’s not at all clear the folks signing off on the original rhetoric were all that clear what it meant in practice even at the time – let alone a century or two later.

Did most of our Founders and Framers speak and write from a nominally Christian paradigm? It certainly seems so, yes. Before we get too excited about emulating this in the 21st century, however, we should keep in mind that it even the most tolerant among them were seriously uncomfortable with Catholics and largely excluded Jews and Muslims from the mix when speaking lofty thoughts about the role of religion in American life. Atheists simply weren’t included in the conversation as real Americans, and the only reason the Baptists were tolerated at all was that at least they weren’t Atheists.

In other words, it’s one thing to explore the context and expressed intentions behind our founding documents; it’s another to embrace their specific implementation and interpretation on the day they were first committed to parchment. Like Socrates, Hippocrates, or Hendrix, sometimes it’s the spirit of the thing more than the details of the moment that matter most.

There’s one other issue I figure I should at least address up front in hopes it will make me sound profound and thoughtful…

How does a nation of diverse backgrounds, races, religions, languages, political ideologies, and lifestyles hold together? If the U.S. was to some extent built on a rejection of “the old ways” – the biases and bondages considered normal across most of the civilized world for many centuries – what do we embrace in their place?

We love talking about America’s “great melting pot,” but implicit in this analogy is the idea that ingredients are intended to become more or less indistinguishable – to end up tasting all the same. Most of us would defend individuality and cohesiveness (or “domestic tranquility,” if you prefer) in equal measure, but these two things actually pull against one another – sometimes dramatically. Like freedom and security they may both be worth defending, but doing so requires we first recognize that neither naturally compliments the other.

Such has been the nature of society since its beginnings. Most political scientists and historians will tell you that the foundation of civilization is the “social contract.” While definitions vary, the basic idea is that at some point people with absolute freedom (think running naked in the woods with a pointy stick in one hand and a dead squirrel in the other) came together and agreed that each would sacrifice a degree of personal freedom for the good of the whole. This is not done from altruism; each member is part of that whole that shares in the benefit. The birth of agriculture allowed specialization and diversification so that while some people still grew food or hunted game, others could focus on arts, crafts, warfare, architecture, philosophy, or entertainment.

In modern times this means we can all have different jobs and simply buy the stuff we need to live – food, shelter, streaming services, etc. It also means that I’ll sit at a red light for what feels like hours even when no one else is at the intersection because I expect you to do the same – and both of us consequently feel safer going through that intersection once the light is green. Freedom and society are not natural allies. It makes sense that trying to maintain both of them in such a large, diverse nation would prove problematic from time to time.

One institution with the potential to offer some sort of national bonding in the 21st century is public education. I’m not suggesting it’s the only answer or even the best at it in practice, but I will insist it should be pretty high on the priority list. Whatever else education can or should do for our national experiment to survive, it must help us do a better job of understanding each other and the issues confronting us as a people – whether scientific, cultural, ethical, political, economic, or anything else. It should offer us the tools necessary to succeed collectively as well as individually, and to embrace our differences without necessarily sacrificing our own sense of self or our collective understanding of right and wrong.

And yeah, it would be ideal if we all emerged a little better at reading, writing, math, science, and history while we’re at it.

The chapters can be read in order, straight through, which creates something of a natural narrative along the way. Or, if you prefer, you can refer to Appendix A for a general clumping by subject matter and hunt down the cases of most interest to you at the moment. The major chapters are numbered, and the “Worth A Look” cases inserted more or less chronologically among them. I’ve included edited excerpts of majority opinions, as well as a number of concurrences and dissents, which you can read, browse, or skip as you see fit. I respectfully suggest, however, that despite all the gravitas and history-shaping rhetoric, most make for a pretty good read. You were smart enough to buy this book; you can handle a little jurisprudential exfoliating. I’ve done my best to maintain intellectual and legal accuracy while at times taking liberties with the formatting and endless footnoting and internal citations and such in order to maintain flow and clarity. Appendix B has a list of some of my favorite books and resources in case you find yourself interested in learning a bit more or arguing with me about how badly I’ve misunderstood or distorted everything important about America.

Speaking of which, I’d love to hear your thoughts or opinions if you find yourself so inclined. You can find me at bluecerealeducation.com or email me anytime at [email protected]. Happy reading.

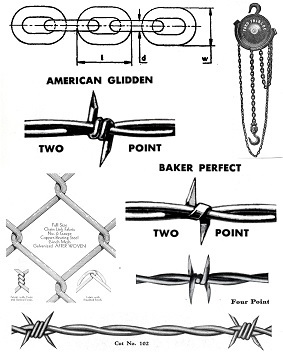

There are barbed wire museums in nearly a dozen different states. That’s right – museums devoted exclusively (or at least primarily) to the origins and impact of pokey wires in all its many varieties. The Oklahoma Cowboy Museum boasts over 8,000 varieties of prickly steel yarn, while the Devil’s Rope Museum in McLean, Texas, promises “everything you want to know about barbed wire and fencing tools.” There are several collections in and around DeKalb, Illinois, the birthplace of barbed wire, but it’s the Kansas Barbed Wire Museum which makes the grandest claims and boasts the most extensive curated exploration of this marvelous innovation.

There are barbed wire museums in nearly a dozen different states. That’s right – museums devoted exclusively (or at least primarily) to the origins and impact of pokey wires in all its many varieties. The Oklahoma Cowboy Museum boasts over 8,000 varieties of prickly steel yarn, while the Devil’s Rope Museum in McLean, Texas, promises “everything you want to know about barbed wire and fencing tools.” There are several collections in and around DeKalb, Illinois, the birthplace of barbed wire, but it’s the Kansas Barbed Wire Museum which makes the grandest claims and boasts the most extensive curated exploration of this marvelous innovation. In the meantime, demand for beef was rising. Soldiers insisted on eating from time to time and all that meat has to come from somewhere. After the war, a prosperous and victorious North wanted steak for dinner. Creative cross-breeding eventually produced a fairly hearty steer which was nevertheless edible – the Texas Longhorn. Railroads connecting the west to markets in the northeast didn’t quite reach Texas, so the age of the great cattle drives was born. Despite its eternal popularity in TV and movie westerns, the era of “git along little doggie” was really only about two decades long – from the 1850s to mid-1870s. By the 1910s… nothing.

In the meantime, demand for beef was rising. Soldiers insisted on eating from time to time and all that meat has to come from somewhere. After the war, a prosperous and victorious North wanted steak for dinner. Creative cross-breeding eventually produced a fairly hearty steer which was nevertheless edible – the Texas Longhorn. Railroads connecting the west to markets in the northeast didn’t quite reach Texas, so the age of the great cattle drives was born. Despite its eternal popularity in TV and movie westerns, the era of “git along little doggie” was really only about two decades long – from the 1850s to mid-1870s. By the 1910s… nothing. This nasty little innovation shifted the balance of power in the west considerably. Pretty much anyone could easily stake out and claim any section of land they wished, whether they legally owned it or not. Sure, you could sneak in and cut the wires, but unlike wooden fences they could be repaired and replaced just as quickly. You could try to go over, under, or through, but the wire itself discouraged this by its very nature. Barbed wire wasn’t the only reason homesteaders and private property took over the west, but it was arguably the deciding factor. As to cattle drives, yes, the railroads finally reached Texas. There were also a few brutal winters in the 1880s which killed tons of livestock. While less dramatic, there’s no denying the impact of wave after wave of desperate settlers now armed with the ability to slice the frontier into private little homesteads defended by cheap, durable, pokey wire fence.

This nasty little innovation shifted the balance of power in the west considerably. Pretty much anyone could easily stake out and claim any section of land they wished, whether they legally owned it or not. Sure, you could sneak in and cut the wires, but unlike wooden fences they could be repaired and replaced just as quickly. You could try to go over, under, or through, but the wire itself discouraged this by its very nature. Barbed wire wasn’t the only reason homesteaders and private property took over the west, but it was arguably the deciding factor. As to cattle drives, yes, the railroads finally reached Texas. There were also a few brutal winters in the 1880s which killed tons of livestock. While less dramatic, there’s no denying the impact of wave after wave of desperate settlers now armed with the ability to slice the frontier into private little homesteads defended by cheap, durable, pokey wire fence. There’s no substitute for actual historical details and legitimate reasoning, but sometimes we want to dangle something a bit more profound out there and hope it catches the teacher’s imagination. The trick is not to push it further than you can back up with actual thought and substance – let them be thrilled at the potential you’re showing, not dismayed by your grandiose nonsense.

There’s no substitute for actual historical details and legitimate reasoning, but sometimes we want to dangle something a bit more profound out there and hope it catches the teacher’s imagination. The trick is not to push it further than you can back up with actual thought and substance – let them be thrilled at the potential you’re showing, not dismayed by your grandiose nonsense. There’s a difference between caring how well you’re actually doing your job and caring how well you do on official evaluations. Ideally, the two at least overlap – like a Venn Diagram or pop and hip-hop. That’s not always a given, however. In practice, it’s often more like the relationship between reality and reality TV.

There’s a difference between caring how well you’re actually doing your job and caring how well you do on official evaluations. Ideally, the two at least overlap – like a Venn Diagram or pop and hip-hop. That’s not always a given, however. In practice, it’s often more like the relationship between reality and reality TV. Teacher evaluation rubrics usually involve detailed sub-categories cascading for pages under ranking columns with names like “Excellent,” “Adequate,” “Could Be Better,” “My God You Suck,” and “Not Observed.” These are laid out in a giant spreadsheet or in an iPad app with descriptions of where a teacher might land on each measured characteristic.

Teacher evaluation rubrics usually involve detailed sub-categories cascading for pages under ranking columns with names like “Excellent,” “Adequate,” “Could Be Better,” “My God You Suck,” and “Not Observed.” These are laid out in a giant spreadsheet or in an iPad app with descriptions of where a teacher might land on each measured characteristic. Here’s the other thing: it doesn’t matter if there’s a pandemic or if every teacher in the building is a Mr. Miyagi, Dewey Finn, or John Keating. “High expectations” means a percentage of them have to be scored harshly because “high expectations.” It’s like a college course being graded on a curve and there were going to be 3 ‘A’s, 10 ‘B’s, 12 ‘C’s, 10 ‘D’s, and 3 ‘F’s no matter how well or poorly individuals might actually do. Oh, and your grade for the entire course is based solely on page 3 of one of the 12 essays you’re required to do that semester.

Here’s the other thing: it doesn’t matter if there’s a pandemic or if every teacher in the building is a Mr. Miyagi, Dewey Finn, or John Keating. “High expectations” means a percentage of them have to be scored harshly because “high expectations.” It’s like a college course being graded on a curve and there were going to be 3 ‘A’s, 10 ‘B’s, 12 ‘C’s, 10 ‘D’s, and 3 ‘F’s no matter how well or poorly individuals might actually do. Oh, and your grade for the entire course is based solely on page 3 of one of the 12 essays you’re required to do that semester. It didn’t go well. He was marked down for things like insufficient connections to prior knowledge – despite the evaluating administrator arriving 10 minutes after the lesson started and the kids not actually having much in the way of applicable prior knowledge. Two kids were doing other things on their iPads which he couldn’t see but the administrator could, meaning he lacked “awareness.” Other than that, it was lots of blank stares and hostile body language. (Also, the kids didn’t seem that glad to be there either.)

It didn’t go well. He was marked down for things like insufficient connections to prior knowledge – despite the evaluating administrator arriving 10 minutes after the lesson started and the kids not actually having much in the way of applicable prior knowledge. Two kids were doing other things on their iPads which he couldn’t see but the administrator could, meaning he lacked “awareness.” Other than that, it was lots of blank stares and hostile body language. (Also, the kids didn’t seem that glad to be there either.) The day before the visit, the building principal came on the intercom and announced that tardies were out of control and that teachers were to lock their doors when the bell rang – no exceptions. Those students would report to detention for the rest of the period. (1st period, unsurprisingly, has more tardies than any other hour.) That announcement was followed by a list of all the busses running late that day. There were always at least 3 – 4; that day Mr. Lutum estimates it was more like 7.

The day before the visit, the building principal came on the intercom and announced that tardies were out of control and that teachers were to lock their doors when the bell rang – no exceptions. Those students would report to detention for the rest of the period. (1st period, unsurprisingly, has more tardies than any other hour.) That announcement was followed by a list of all the busses running late that day. There were always at least 3 – 4; that day Mr. Lutum estimates it was more like 7.

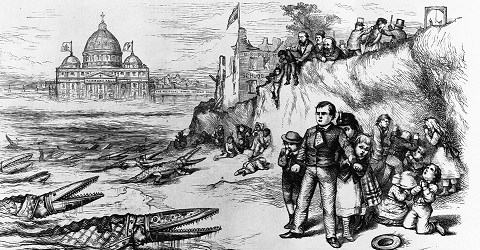

While it was not always mentioned by name, several major decisions of the Court in the early 21st century very much involved the history and potential future of the “Blaine Amendment.” Blaine is a general label applied to various provisions in 37 different state constitutions limiting or prohibiting the use of state funds to support religious organizations or sectarian activity. The precise wording and application vary from state to state, and 13 states don’t have one at all. Most Blaine Amendments are actually sections or clauses in their respective state constitutions and not “amendments” at all, but the term has proven persistent. Plus, it’s used in the singular (collectively) or plural more or less interchangeably – so that’s kinda fun.

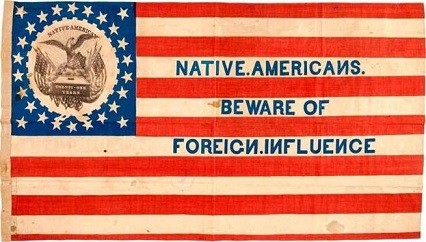

While it was not always mentioned by name, several major decisions of the Court in the early 21st century very much involved the history and potential future of the “Blaine Amendment.” Blaine is a general label applied to various provisions in 37 different state constitutions limiting or prohibiting the use of state funds to support religious organizations or sectarian activity. The precise wording and application vary from state to state, and 13 states don’t have one at all. Most Blaine Amendments are actually sections or clauses in their respective state constitutions and not “amendments” at all, but the term has proven persistent. Plus, it’s used in the singular (collectively) or plural more or less interchangeably – so that’s kinda fun. The Know-Nothings, who actually called themselves “The American Party,” were the MAGA of their day – slogan driven, easily triggered, and fiercely patriotic (as long as the nation they perpetually celebrated prioritized those who looked and thought as they did). They didn’t have a “dark web” or the chance to go giddy over secret Q-Anon symbols encoded in the evening news, but they did their best to be melodramatic nonetheless. When asked about their political druthers or anything related to the party itself, members were expected to go full Sgt. Schultz and claim to “know nothing” – hence the nickname.

The Know-Nothings, who actually called themselves “The American Party,” were the MAGA of their day – slogan driven, easily triggered, and fiercely patriotic (as long as the nation they perpetually celebrated prioritized those who looked and thought as they did). They didn’t have a “dark web” or the chance to go giddy over secret Q-Anon symbols encoded in the evening news, but they did their best to be melodramatic nonetheless. When asked about their political druthers or anything related to the party itself, members were expected to go full Sgt. Schultz and claim to “know nothing” – hence the nickname. More recently, in 2018, the Supreme Court upheld then-President Trump’s “Muslim Ban” on travel from a half-dozen countries. Trump had promised a “Muslim Ban,” his agents fought for a “Muslim Ban,” and his supporters celebrated the proclamation of a “Muslim Ban” because it was about time we started banning those Muslims with a Muslim Ban that bans them darned Muslims! After backlash from the courts, however, the administration managed to tweak the language enough that it could conceivably be viewed by someone who’d missed all the kerfuffle as a valid national security measure that only coincidentally sorta looked a great deal like a Muslim Ban. (It probably helped that they crossed out the title “Muslim Ban” at the top and scribbled “Valid National Security Measure” in orange crayon.) It was this “Huh? A ‘Muslim Ban’? Who told you THAT?” version the Supreme Court chose to validate, treating the act’s obvious intent and recent history like mysteries lost to the ages and certainly of no relevance to this shiny new valid security measure before them.

More recently, in 2018, the Supreme Court upheld then-President Trump’s “Muslim Ban” on travel from a half-dozen countries. Trump had promised a “Muslim Ban,” his agents fought for a “Muslim Ban,” and his supporters celebrated the proclamation of a “Muslim Ban” because it was about time we started banning those Muslims with a Muslim Ban that bans them darned Muslims! After backlash from the courts, however, the administration managed to tweak the language enough that it could conceivably be viewed by someone who’d missed all the kerfuffle as a valid national security measure that only coincidentally sorta looked a great deal like a Muslim Ban. (It probably helped that they crossed out the title “Muslim Ban” at the top and scribbled “Valid National Security Measure” in orange crayon.) It was this “Huh? A ‘Muslim Ban’? Who told you THAT?” version the Supreme Court chose to validate, treating the act’s obvious intent and recent history like mysteries lost to the ages and certainly of no relevance to this shiny new valid security measure before them. Then, in 2017, a particularly conservative Court decided that the whole “wall of separation” thing was overblown. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017), the Court ruled that if the state was going to offer ANY public institutions financial support – in this case, new bouncy rubber “gravel” for their playgrounds – it had to include religious institutions in the mix no matter what the state constitution might say or the original program intend. Hence Trinity Lutheran, an overtly religious institution which proudly proclaimed that everything it did and every facility under its control was there to bring little children to Jesus, would receive the same check directly out of state funds as the public school playground down the street which was just there so kids had a safe place to play – or perhaps instead of it. Blaine was now clearly on life support but still taking up bed space.

Then, in 2017, a particularly conservative Court decided that the whole “wall of separation” thing was overblown. In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017), the Court ruled that if the state was going to offer ANY public institutions financial support – in this case, new bouncy rubber “gravel” for their playgrounds – it had to include religious institutions in the mix no matter what the state constitution might say or the original program intend. Hence Trinity Lutheran, an overtly religious institution which proudly proclaimed that everything it did and every facility under its control was there to bring little children to Jesus, would receive the same check directly out of state funds as the public school playground down the street which was just there so kids had a safe place to play – or perhaps instead of it. Blaine was now clearly on life support but still taking up bed space.