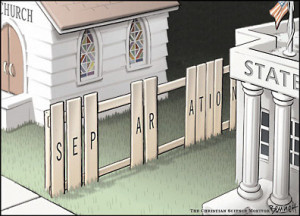

Well, any pretense Chief Justice John Roberts has been maintaining about being in any way “moderate” or “reasonable” seems to have been blown to hell this week. The Court’s decision in Carson v. Makin (2022) accelerates the jurisprudential slide away from the proverbial “wall of separation” and elevates the “free exercise” of the minority with the most influence in federal government over the right of anyone else not to pay for it. In the process, the Supreme Court is now openly deriding the suggestion that states have an obligation (or even the right?) to provide a secular public education for kids to begin with.

Well, any pretense Chief Justice John Roberts has been maintaining about being in any way “moderate” or “reasonable” seems to have been blown to hell this week. The Court’s decision in Carson v. Makin (2022) accelerates the jurisprudential slide away from the proverbial “wall of separation” and elevates the “free exercise” of the minority with the most influence in federal government over the right of anyone else not to pay for it. In the process, the Supreme Court is now openly deriding the suggestion that states have an obligation (or even the right?) to provide a secular public education for kids to begin with.

In Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), the Supreme Court decided that state voucher programs providing funding for students to attend private schools – even religious institutions – can be constitutional. It relied heavily on the role of “parent choice” to determine where state funds were actually spent. Even if the majority of vouchers were used at private religious institutions, as long as there were valid secular options and the choices were made by families rather than the government, the program did not violate the Establishment Clause.

In Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc., v. Comer (2017), the Court required the state of Missouri to include churches or other religious organization in a state program to modernize playgrounds. This was the first time the Court determined that the U.S. Constitution required government to provide direct public assistance to religious institutions. In so doing, it called into question the validity of “the Blaine Amendment” – provisions in many state constitutions which prohibit direct support of sectarian institutions. Usually, this meant schools.

In Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue (2020), the Court determined that excluding religious schools from voucher programs violated the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment. The Court had previously distinguished between what funds were being used to DO (meaning that general good being done by religious institutions might still qualify for public funding) vs. distinctions based on what an institution WAS or BELIEVED. Restricting public funding based on what was being promoted might be OK; restricting it based on the beliefs or values of the institution was NOT. In Espinoza, despite token acknowledgement of this historical consideration in the majority opinion, in practice the distinction was clearly beginning to crumble.

In Our Lady of Guadalupe School v. Morrissey-Berry (2020), the Supreme Court extended its earlier ruling in Hosanna-Tabor Evangelical Lutheran Church and School v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (2012) and determined that for purposes of hiring, firing, or other human resources type decisions, teachers and staff at religious schools were clergy. Normal protections regarding age, illness, sexuality, political affiliations, race, unexpected life events, etc., simply did not and could not apply. It didn’t matter whether the teacher in question was even a member of the faith – they could be hired and fired at will and treated however the institution wishes to treat them with little redress.

As I said so very profoundly in “Have To” History: A Wall of Education…

The combination of Espinoza v. Montana and Our Lady of Guadalupe (decided during the same session) seemed to set up something of a paradox. Private religious schools are primarily “schools” when it’s time to hand out tax dollars but primarily “churches” when the specter of accountability appears. This is a tad frustrating for public school advocates who see tax dollars being redirected for religious uses minus any real expectations or accountability.

I know – makes you wish you’d already bought the book, doesn’t it?

Now comes Carson v. Makin, in which the Court has just ruled that if Maine wishes to provide ANY assistance or aid to non-public schools, it cannot exclude religious institutions, no matter what policies they uphold or which doctrines they teach as part of that education. This is particularly problematic in Maine, where apparently there are many areas without secondary public schooling options, but the larger principle will impact educational institutions in every state, regardless of local wishes or logistics.

I’ll post a separate breakdown of the ruling in the next few days, but for now I’ll simply link to some of the better summaries of the decision by others. I don’t think any of them are behind paywalls, but honestly I lose track sometimes, so my apologies if any of the links take you to a dead end.

“Supreme Court Rejects Maine’s Ban on Aid to Religious Schools” (The New York Times) – this is one of the more balanced and succinct articles on the list and a good place to start if you don’t know much about the case to begin with.

“The Supreme Court Just Forced Maine to Fund Religious Education. It Won’t Stop There.” (Slate) – this one offers excellent analysis of the likely impact of this case and shares many of my own concerns. There are also plenty of helpful links to related cases and analyses embedded in the article itself. As a teaser, here’s the opening paragraph:

The Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority effectively declared on Tuesday that the separation of church and state—a principle enshrined in the Constitution—is, itself, unconstitutional. Its 6–3 decision in Carson v. Makin requires Maine to give public money to private religious schools, steamrolling decades of precedent in a race to compel state funding of religion. Carson is radical enough on its own, but the implications of the ruling are even more frightening: As Justice Stephen Breyer noted in dissent, it has the potential to dismantle secular public education in the United States.

“The Supreme Court Tears a New Hole in the Wall Separating Church and State” (Vox) – another excellent analysis of the case, although the tone is slightly less horrified than that of the folks at Slate or myself. I particularly like this analogy:

Think of it this way: Suppose that a state provides grants to help private institutions set up food banks and soup kitchens. If a church sought one of these grants, it could not be denied because of its Christian identity. But the state could require the church to spend 100 percent of the grant money it receives on secular activities such as feeding the poor, and not on religious activity such as distributing Bibles to the needy.

Carson effectively eliminates this distinction between organizations that have a religious identity, and organizations that want to use government funds for religious purposes. After Carson, a private school may not only receive a government tuition subsidy, it may also use that subsidy to fund explicitly religious instruction.

Even if you’re a religious person yourself, which specific theology do you think it’s most likely your tax dollars will be supporting going forward? If you need a hint, check out the dominant voices in the Republican Party over the past few years.

“Court’s Excellent Free-Exercise Ruling in Carson v. Makin” (National Review) – even if you’re not familiar with National Review, the title should tip you off that they’re not at all displeased with this decision. I’m including this piece partly to pretend I’m fair and balanced, but mostly because it includes some relevant background and perspective not present in the other links. Like most conservative voices, it deals with the worst of the decision by simply ignoring the obvious ramifications, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth a read.

“How Supreme Court Ruling Lays Groundwork for Religious Charter Schools” (The Washington Post) – I have a digital subscription, but WP might do one of those “limited number of free articles” things. This one covers the important stuff but focuses especially on the “status-use distinction” mentioned above.

Finally, here’s a PDF of the Court’s written decision, including dissents from the usual suspects. As I’ve lovingly suggested in both of my books on our nation’s highest court, these aren’t as hard to read as they may seem when you first peruse them. Some of the language gets wonky, and the formatting is at times off-putting, but most of the various opinions are quite accessible and worth your time.

I hope to give this one further attention and perhaps draw attention to my own thoughts and concerns in the next few days. As always, your comments are welcome below.

If you keep up with education news at all, you know all the usual struggles – class sizes, standardized testing, general hostility towards educators by whoever’s looking to score points with conservatives that week, etc. One of the biggies is the ongoing battle to keep the arts in public education. Every time budgets are tight (and they usually are), one of the first things to go is music, or the visual arts, or drama. Even when those classes survive, they’re the first to become “dumping grounds” for students who’ve shown no particular interest in anything but have to be SOMEWHERE. “Hey, anyone can draw a picture or hit a drum, right?”

If you keep up with education news at all, you know all the usual struggles – class sizes, standardized testing, general hostility towards educators by whoever’s looking to score points with conservatives that week, etc. One of the biggies is the ongoing battle to keep the arts in public education. Every time budgets are tight (and they usually are), one of the first things to go is music, or the visual arts, or drama. Even when those classes survive, they’re the first to become “dumping grounds” for students who’ve shown no particular interest in anything but have to be SOMEWHERE. “Hey, anyone can draw a picture or hit a drum, right?” One of the coaches in my district approached me last week and asked if I had a moment to talk about a few students. Each of them had come pretty close to passing my class but had fallen short largely due to things entirely within their control – not turning in study guides for easy points, not participating in review sessions, etc.

One of the coaches in my district approached me last week and asked if I had a moment to talk about a few students. Each of them had come pretty close to passing my class but had fallen short largely due to things entirely within their control – not turning in study guides for easy points, not participating in review sessions, etc. The first was how graciously he approached the issue. He wanted to make sure there was nothing suggesting pressure from him or anyone else to do anything I might be uncomfortable with or consider unethical – and I think he meant it. These kids weren’t athletic superstars or anything. I teach freshmen, and while they may have potential, none of them are critical to the success of anything happening on a track, field, or court next year. In his mind, it was about what being involved and playing sports MIGHT do for them overall – including, but not limited to, academically.

The first was how graciously he approached the issue. He wanted to make sure there was nothing suggesting pressure from him or anyone else to do anything I might be uncomfortable with or consider unethical – and I think he meant it. These kids weren’t athletic superstars or anything. I teach freshmen, and while they may have potential, none of them are critical to the success of anything happening on a track, field, or court next year. In his mind, it was about what being involved and playing sports MIGHT do for them overall – including, but not limited to, academically. The second reason I considered his question is that the kids in question are genuinely good kids, at least most of the time. They’ve each shown flashes of far more ability than their grades would suggest. I know something of their hopes and visions for their futures, and while ambitious, they’re all certainly plausible. (None of them are counting on the NBA or YouTube stardom to get them through adulthood.) These weren’t kids with a 12% or a history of serious discipline problems; they just didn’t always show the focus or determination one might hope.

The second reason I considered his question is that the kids in question are genuinely good kids, at least most of the time. They’ve each shown flashes of far more ability than their grades would suggest. I know something of their hopes and visions for their futures, and while ambitious, they’re all certainly plausible. (None of them are counting on the NBA or YouTube stardom to get them through adulthood.) These weren’t kids with a 12% or a history of serious discipline problems; they just didn’t always show the focus or determination one might hope. Finally, there was my stubborn belief in the power of extracurriculars in kids’ lives. I’ve had the honor of working closely with

Finally, there was my stubborn belief in the power of extracurriculars in kids’ lives. I’ve had the honor of working closely with  So the question before me was one of probabilities and teacher philosophy. Coach was quite transparent about the fact that he couldn’t guarantee anything either way. While he hoped he’d be able to work with these kids as they continued through high school, there was no certainty they’d stay on the team. Playing or not, there was no way to know if they’d take advantage of the extra support and improve academically going forward. It’s possible I might nudge their grades up a few percentage points and all I’d be doing was feeding their delusions about how school works.

So the question before me was one of probabilities and teacher philosophy. Coach was quite transparent about the fact that he couldn’t guarantee anything either way. While he hoped he’d be able to work with these kids as they continued through high school, there was no certainty they’d stay on the team. Playing or not, there was no way to know if they’d take advantage of the extra support and improve academically going forward. It’s possible I might nudge their grades up a few percentage points and all I’d be doing was feeding their delusions about how school works. There was one other reality to consider. While there’s no doubt in my mind any of these kids could have passed my class with a little more effort, the true difference between a 57% and a 61% is painfully subjective and impacted by any number of factors. I’d love to tell you that my English instruction and assessment is so data-driven and pedagogically holy that every tenth of a percentage point reflects a very specific level of skills and knowledge in each student, but

There was one other reality to consider. While there’s no doubt in my mind any of these kids could have passed my class with a little more effort, the true difference between a 57% and a 61% is painfully subjective and impacted by any number of factors. I’d love to tell you that my English instruction and assessment is so data-driven and pedagogically holy that every tenth of a percentage point reflects a very specific level of skills and knowledge in each student, but  If I do it, I told my colleague, the students would have to be fully informed of the decision (as opposed to thinking they’d somehow “slid by” at the last minute). This isn’t about wanting credit for the decision (I’m not sure enough of myself to feel too pious about it). It’s about wanting them to understand the reasoning behind it and the opportunity they have to take advantage of the moment. “There are adults in this building who believe you have better things in you than what you’ve shown so far and who want to give you the chance to express them. We’re trying to open the door a bit; what you do with it is up to you.”

If I do it, I told my colleague, the students would have to be fully informed of the decision (as opposed to thinking they’d somehow “slid by” at the last minute). This isn’t about wanting credit for the decision (I’m not sure enough of myself to feel too pious about it). It’s about wanting them to understand the reasoning behind it and the opportunity they have to take advantage of the moment. “There are adults in this building who believe you have better things in you than what you’ve shown so far and who want to give you the chance to express them. We’re trying to open the door a bit; what you do with it is up to you.”

I wrote recently about

I wrote recently about