NOTE: I’m toying with the idea of a follow-up volume to both “Have To” History: Landmark Supreme Court Cases and “Have To” History: A Wall of Separation. The working title is Stomping Decisis (I’ll probably change it if I can think of something better) and the central subject would be major Supreme Court decisions of the Roberts Court with focus on the past few years and the nature of the Court’s lurch to the far right. We’ll see if it actually happens.

What follows is a rough draft of one possible introduction. I’ve begun playing with the intro this early in the process because I’m trying to figure out the exact approach and “shape” of the book if I actually end up writing it. I’m not even sure at this point if this intro even makes sense or fits where the book is likely to go, but one sure way to get honest feedback is to put it out there and see what happens. Plus, I haven’t posted anything in over a week, and it seemed time.

As always, your comments and questions are welcome below or via email. You are appreciated.

Stomping Decisis (Introduction)

Stomping Decisis (Introduction)

In the spring and summer of 2022, the United States Supreme Court began announcing its findings in the dozens of cases it chose to hear that session. As its decisions began to circulate, there was much rejoicing on the far right and substantial shock from progressives and moderates at the radical direction the Court seemed to be taking. Apparently, social media informed us, states now have to pay for religious education (including overt homophobia and science denial) and public school teachers can pray in front of their students. States are no longer allowed to regulate guns and the C.I.A. doesn’t have to tell anyone the locations of its favorite torture chambers. The Environmental Protection Agency is prohibited from protecting the environment quite so much. Oh, and yes – Roe v. Wade has been overturned. Everyone who gets pregnant for any reason, with their cooperation or without, must now carry the child through delivery whether it’s alive or dead and whether they’re likely to survive the experience or not.

What the hell happened?

That’s what we’re going to look at in the following pages – once we get through a few spoilers by way of context.

First, while the Court’s decisions absolutely indicate a lurch to the far right, the descriptions above aren’t entirely accurate or fair – at least not for every case. The emotional reactions many of us experienced (and may still be experiencing) are perfectly understandable and perhaps even justified, but once our collective blood pressure has stabilized a bit, it’s worth looking at precisely what the Court did and didn’t say in its recent decisions. It’s not always as insane as it sounds at first. (Well, except some of the parts written by Justice Thomas.)

Second, shifts like these rarely come completely out of nowhere. It’s easy to miss the signs along the way because most of us have busy lives and other things to pay attention to. When we hear on the news that the Court “saved” the Affordable Care Act or neglected to overturn Roe, we file it all away under “no change” even if that’s not the full story. We rarely dig deeper to see what, in fact, they did say. Sometimes the details just aren’t quite right yet. Other times, the Court is still too ideologically balanced to allow destabilizing lurches to the left or right without better reasons.

Spoiler alert: that last one is not currently an issue. The far right is in complete control of this Court and will be for the foreseeable future.

Finally, many of the issues addressed in these cases are simplified and summarized as a practical matter during most media coverage. The Court’s reasoning can get a bit verbose or technical. Other times, there are legal technicalities impacting the specific decision but not directly related to the larger issues involved. And, to be fair, the average American isn’t well-known for their firm grasp on the U.S. Constitution and its amendments or landmark jurisprudence over the past century.

If that’s you, don’t feel too bad – it’s possible you’ve simply had better things to do than slog through this stuff repeatedly during each slew of announcements.

A Matter Of Degrees

Activists and ideologues have a vested interest in keeping their audiences as stirred up as possible by unfolding events. (That doesn’t mean they’re always wrong – merely that they’re not always the most rational, balanced folks in the conversation.) One of the most foundational means of maintaining this is to repeatedly frame everything in terms of dichotomies – this belief vs. that one, this value vs. the opposite value, and perhaps most importantly, us vs. them.

In reality, however, there aren’t that many issues over which a clear majority of Americans absolutely, dogmatically disagree in all possible situations. Most of the time, controversies come down to matters of degrees. We’re often working with the same basic sliding scale; we just don’t like where the other guy is trying to mark what’s acceptable and what’s not in ways which then impact all of us.

Take, for example, the issue of religion in public schools. There are two clauses in the First Amendment which involve religion – the very first two, in fact:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof…”

That’s it. Sixteen words. These are where all the kerfuffles begin.

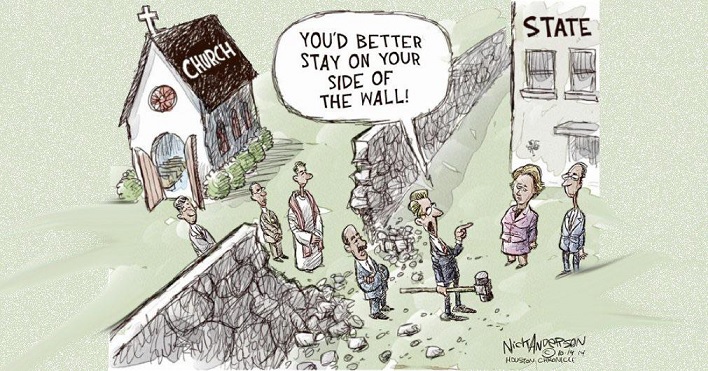

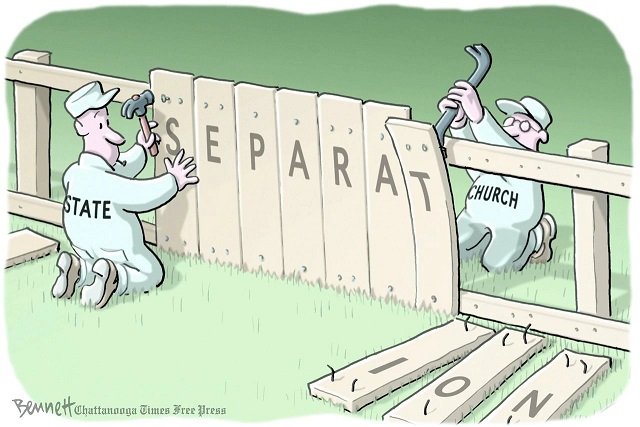

The first bit is known as the Establishment Clause. It’s widely understood to mean that government (including states and local governments, thanks to the Fourteenth Amendment) should avoid doing anything that promotes religion in general, or one type of religion or belief system over another. The second part is the Free Exercise Clause. It says that government shouldn’t do anything to hinder or punish religious beliefs or practices. In short, government at all levels should simply stay out of people’s religions.

It certainly sounds straightforward enough. How hard could this be?

Now, imagine that there’s a fire in a little Methodist church down the street from wherever you are now. You’ve never been there, but they seem nice enough. Should the fire department rush to the scene and try to save the church, or merely stand by ready to protect nearby homes and businesses if the flame starts to spread?

Most people would insist that the fire department should respond and treat the situation the same way they would any other fire. I could argue, however, that this is a violation of the Establishment Clause because the city is using public resources to promote religion. The faster those firefighters respond and the harder they work, the less damage that fire will do and the more resources that little church will have left over to proselytize and organize potlucks and run Vacation Bible School over the summer.

The same is true of police protection. Road repairs. Ambulance service. You get the idea. Our tax dollars help religious people and organizations all the time. If state or local government refused to do for that little church what it does for every everyone else in town just, it would in effect be punishing church members for their faith. If they wish to participate in the traditions and activities of their religion, they must give up benefits they could have if they weren’t being all “religious.”

Sliding The Scales

Now let’s imagine that we’re not talking about fire or police protection, but public transportation. The city has invested in some stylin’ new shuttles and wants to make it easy for people to get around, no matter what their income levels. There’s a small cost for a ticket to the airport, the mall, downtown, or the theater district, but tickets are free for passengers going to school, a public library, the local health department, or any of the churches along the route – including that little Methodist chapel we’ve been discussing.

How about now? Is this the same as fire protection and road repairs, or is this a special benefit for religion? It’s not even for all religions – just churches which happen to be near established routes! We’re still pretty close to the “put out the fire” end of the scale, but we’re definitely moving a bit.

Maybe the county has been given funding to improve the lives of children in the area. As part of this, they’re offering to pay for playground upgrades (including that bouncy foam stuff to replace dirt or sand) for any qualifying site. Several schools secure the grant, as does the privately managed area outside the Children’s Science Museum across town. Should our church down the street be allowed to apply as well on the same terms as everyone else? On the one hand, it’s just a playground. On the other, they make no secret of their desire to bring kids into their faith. They use their playground extensively on Sundays and during Vacation Bible School, even though it’s accessible to the neighborhood year-round.

We’re definitely further along that scale now. Are you still comfortable with letting them partake, or have we crossed a line somewhere along the way from “free exercise” to “establishment”?

As the church grows, perhaps they add a homeless shelter and food pantry comparable to those in other parts of town which receive government grants to support their efforts and ask for similar assistance. Should the state allot funds to this location as well? Would it be OK if the state only provided funds on the condition they be used exclusively for food and shelter and not in direct support of proselytizing or other religious teaching? Does such a distinction even matter when every dollar the church doesn’t have to spend on bread and peanut butter can go to providing Bibles?

Where are we on that scale now?

Homelessness often involves mental illness or other extenuating circumstances. Now the church wants to incorporate counseling and rehab services. Their personnel are trained professionals, but they’re also faithful Christians who share elements of their faith during discussions with clients. If the state supports these efforts to the same extent they do secular services, they’re definitely supporting religion now – right? So what if they only support the “clinical” parts of the counseling and not the “religious” parts. Like, every time someone mentions Jesus, they hold down a button that stops the timer for a bit or something. What do you think now?

Perhaps there’s a lawyer or two in the congregation and the church gradually becomes a primary provider of adoption services in the area as part of their mission to serve the community around them. They’re not comfortable placing children with same-sex couples or divorced women, however. This service isn’t even receiving direct government funding, although it does have to contend with the complex web of laws regulating adoption and they’ve effectively become the only real option in this half of the state. Should they be allowed to pick and choose who they’ll serve, like restaurants in the 1950s?

While we’re at it, we might as well have our little Methodist church start its own private school and ask for the same per-student funding as the public school down the street. We’re not quite to the opposite end of that sliding scale from where we started, but we’re heading that way at a good clip.

Let’s cap the far end with your legislature declaring the United Methodist Church the official religion of your state and instituting a new tax enabling them to pay for Methodist Preachers and more Methodist buildings. They will not, however, imprison or execute you for believing differently – as long as you pay your taxes. Unless you’re Clarence Thomas, you probably wouldn’t consider that a good balance between establishment and free exercise, meaning somewhere along our scale (or in one of the endless variations continually complicating the issue in real life), you decided there’d been enough “free exercise” and the government was now veering into “establishment.” Lines needed to be drawn to clarify the difference.

And, if you’re like most Americans, you consider wherever you drew the line to be so obvious that anyone too far right or left of your mark is a bit of a wacko, and possibly dangerous.

Staking Out Positions

In each iteration, treating the church’s efforts the same as other institutions risks promoting their religion, thus violating the Establishment Clause. The church’s activities aren’t independent of its beliefs; this particular little church strives to serve people and their community because they believe that’s what Jesus wants them to do. On the other hand, treating the church differently than other groups might very well infringe on their faith by denying them the same cooperation or support they’d receive if they weren’t religious (or if they gave up their faith). This violates the Free Exercise Clause.

Just to complicate things, sometimes the same rules which govern how states or communities relate to or support private organizations are at odds with the specific belief systems of a particular religion. In other words, sometimes treating that little Methodist church the same as everyone else infringes on their free exercise just as much as excluding them altogether. This is when things get really interesting (or maddening, depending on your point of view).

We can argue the details (they’re very much worth arguing), but the point is that the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause pull against one another in ways that mean anytime we try to protect one, there’s a chance we’re offending the other a little bit. I’m not aware of any major “wall of separation” cases in which either party has argued in favor of simply eliminating one clause or the other. Where the disagreement comes is precisely where on that sliding scale the lines should be drawn.

The same sorts of “sliding scales” are present in most debates over the death penalty, immigration policy, reproductive rights, and the like, as well as many issues less likely to end up in the Supreme Court – school dress codes, regulations imposed by your local homeowners’ association, and speed limits just to name a few. This doesn’t suggest that all possible points along each scale are equally defensible or that there are no “right” answers (constitutionally speaking), but recognizing the relative nature of these arguments is often essential to making sense of them along the way and understanding the Court’s rulings and how they sometimes change over time.

That’s what we’re going to try to do here by visiting a variety of recent Supreme Court decisions and what different justices specifically said about those decisions (whether in support or opposition). We’re also going to zoom in on a few representative topics and trace some of their jurisprudential history over the past century in order to better understand where we are now, and why.

At every stage, my goal is to keep things as understandable as possible without overly compromising the substance of each argument or issue. It’s worth keeping in mind that I write this book not as a legal expert, but as an educator with twenty-plus years breaking down complex historical and legal issues for teenagers to better help them wrestle with many of these same subjects for themselves. While I certainly have my own points of view on most of these topics (and you’ll have little trouble figuring out what they are along the way), I’ve made every effort to make this material accessible, enjoyable, and useful for readers of all stripes.

Except Justice Clarence Thomas. I doubt he’d enjoy this one at all.

I’m not a preacher, a prophet, or a theologian. I like too many different colors of children and accept too wide a range of people and their efforts to make sense of this world and their place in it. I don’t worship the police, the military, or the GOP. I don’t even own a gun. So, despite what the current Supreme Court seems to think, I’m probably not the person you want teaching your kids about what American Christianity demands they think, feel, believe, or do.

I’m not a preacher, a prophet, or a theologian. I like too many different colors of children and accept too wide a range of people and their efforts to make sense of this world and their place in it. I don’t worship the police, the military, or the GOP. I don’t even own a gun. So, despite what the current Supreme Court seems to think, I’m probably not the person you want teaching your kids about what American Christianity demands they think, feel, believe, or do.

A few days ago, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Carson v. Makin, a case involving state support of religious education in rural Maine. The short version is that states which offer any sort of support for private schooling or alternatives to state-run public schools cannot deny equivalent support to religious institutions claiming a comparable role. These institutions need not follow state curriculums or abstain from indoctrination. They may pick and choose their students on any basis they like and may teach what they like, however they like, and still get paid by the state for each student they choose to accept.

A few days ago, the Supreme Court announced its decision in Carson v. Makin, a case involving state support of religious education in rural Maine. The short version is that states which offer any sort of support for private schooling or alternatives to state-run public schools cannot deny equivalent support to religious institutions claiming a comparable role. These institutions need not follow state curriculums or abstain from indoctrination. They may pick and choose their students on any basis they like and may teach what they like, however they like, and still get paid by the state for each student they choose to accept.