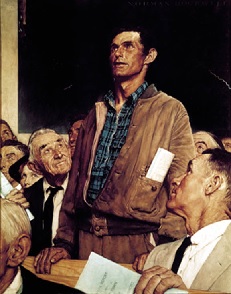

The original element of despotism is a MONOPOLY OF TALENT, which consigns the multitude to comparative ignorance, and secures the balance of knowledge on the side of the rich and the rulers.

If then the healthy existence of a free government be, as the committee believe, rooted in the WILL of the American people, it follows as a necessary consequence, of a government based upon that will, that this monopoly should be broken up, and that the means of equal knowledge, (the only security for equal liberty) should be rendered, by legal provision, the common property of all classes.

In a republic, the people constitute the government, and… frame the laws and create the institutions, that promote their happiness or produce their destruction… It appears, therefore, to the committee that there can be no real liberty without a wide diffusion of real intelligence; that the members of a republic, should all be alike instructed in the nature and character of their equal rights and duties, as human beings, and as citizens…

(Report of the Workingman’s Committee of Philadelphia On the State of Public Instruction in Pennsylvania, 1830)

These were white working men in the semi-industrialized north. They lived in an age of reform – the time of Lucretia Mott, William Lloyd Garrison, Dorothea Dix, and Horace Mann. It is unlikely that most owned land. Their ‘report’ echoes that of other labor organizations of the era – we need universal public education for our kids.

This was not a majority sentiment.

It’s dangerous to project backwards regarding motivations and intentions, but it seems that even when public education was barely a thing, they realized it would soon become essential if their sons were to flourish in the next generation. I don’t know if they were worried about ‘personal fulfillment’ stuff as well, but I’m an idealist, so… let’s assume maybe they did.

It’s dangerous to project backwards regarding motivations and intentions, but it seems that even when public education was barely a thing, they realized it would soon become essential if their sons were to flourish in the next generation. I don’t know if they were worried about ‘personal fulfillment’ stuff as well, but I’m an idealist, so… let’s assume maybe they did.

Their report demonstrates impressive cognizance regarding their target audiences. Rather than plead on behalf their offspring, they argue founding values, and the well-being of the republic to those in positions to change the system – to pass the laws, devote the resources, reshape the society. They don’t ask for opportunities, even democratic ones; rather, they promise better citizens. They reference aristocracy and oligarchy, anathema to ‘real Americans’ a generation after the Revolution, and lay out a simply path towards better functioning. It’s a great argument.

It’s also about a century ahead of its time. Education was starting to matter in 1830, at least in the North, but land was still the universal key.

And then a century passed.

In the 1930’s, everything changed. The Great Depression, of course, and the Dust Bowl – game changers for the nation and for the world. Something else was going on as well, though – an abrupt shift in land ownership and what it meant.

Once California belonged to Mexico and its land to Mexicans; and a horde of tattered feverish Americans poured in. And such was their hunger for land that they took the land… and they guarded with guns the land they had stolen. They put up houses and barns, they turned the earth and planted crops. And these things were possession, and possession was ownership.

The Mexicans… could not resist, because they wanted nothing in the world as frantically as the Americans wanted land.

Steinbeck was entirely capable of being racist by the standards of today, but I don’t think this was one of those times. His venom here is towards what we’d today call “the man,” and he’s mildly sympathetic towards Mexico’s loss. Keep in mind he was essentially a Socialist, which tends to happen to people who spend enough time among the disenfranchised.

Then, with time, the squatters were no longer squatters, but owners; and their children grew up and had children on the land. And the hunger was gone from them, the… tearing hunger for land, for water and earth and the good sky over it… They had these things so completely that they did not know about them any more… and crops were reckoned in dollars, and land was valued by principal plus interest, and crops were bought and sold before they were planted.

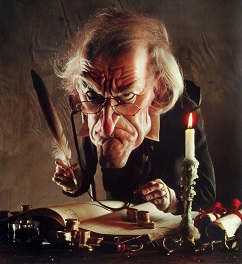

Jefferson would have peed himself. T.J. liked a good income, but he had a healthy sense of delusion regarding the holiness of agriculture as well. Remember Jesus turning over the tables of the money-changers in the temple?

Then crop failure, drought, and flood were no longer little deaths within life, but simple losses of money. And all their love was thinned with money, and all their fierceness dribbled away in interest until they were no longer farmers at all, but little shopkeepers of crops… Then those farmers who were not good shopkeepers lost their land to good shopkeepers. No matter how clever, how loving a man might be with earth and growing things, he could not survive if he were not a good shopkeeper. And as time went on, the business men had the farms, and the farms grew larger, but there were fewer of them…

And there were pitifully few farmers on the land any more…

(John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath – 1939)

Land didn’t work anymore.

It would still grow stuff – more effectively than ever, actually. But it wasn’t LAND (*cue majestic music*) in the way it had been land before. Jefferson’s agricultural ideal was all but extinguished, and the most sacred of pursuits – the one previously regarded as the best possible indication of a man’s capability, responsibility, moral potential, and stake in the prosperity of the nation – became just another business. It mattered, sure – but so did the weaving and the manufacturing and the shipping and the lawyering. It was no longer special.

This is not my anti-capitalism rant. I’ll leave that to Tom Joad and his spirit moving among the hungry children and such. I’m more or less a Libertarian, but the Libertarian Ideal in MY interpretation requires a capable citizenry with actual options and real opportunity. It’s fine to support free will and full consequences for our actions, but to believe this and sleep at night we need something akin to a ‘equitable starting position’ or the proverbial ‘level playing field’.

This is not my anti-capitalism rant. I’ll leave that to Tom Joad and his spirit moving among the hungry children and such. I’m more or less a Libertarian, but the Libertarian Ideal in MY interpretation requires a capable citizenry with actual options and real opportunity. It’s fine to support free will and full consequences for our actions, but to believe this and sleep at night we need something akin to a ‘equitable starting position’ or the proverbial ‘level playing field’.

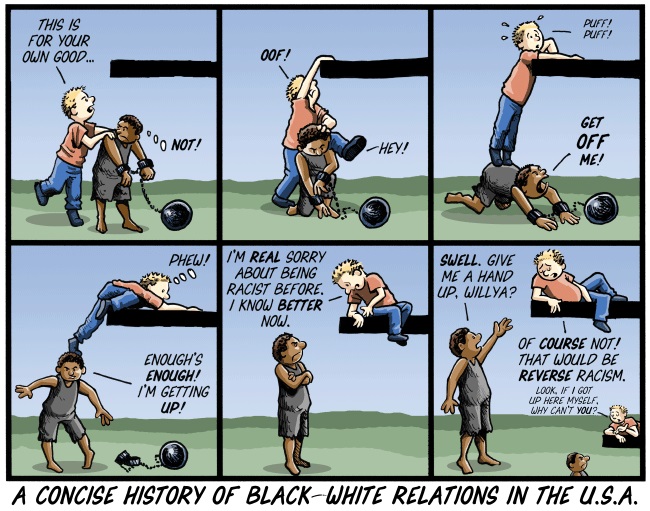

That’s not the same as waiting until you’re way, way ahead, and then suddenly cutting the ropes to the bridge. That’s not libertarianism, that’s just being a bastard. Not always a clear distinction, I realize, but an important one nonetheless.

But I digress.

Land was a big deal. It was readily available by some standards, and not at all available by others. It came to define more than your right to vote or otherwise participate – it blurred into individual worth and identity. It was taken from the Amerindians, who didn’t even buy into the system, and denied to Black Americans, who did. Eventually, it ceased to be what it had been – the key to opportunity, responsibility, capability… all the -ilities.

“Ma,” she said. Ma’s eyes lighted up and she drew her attention toward Rose of Sharon. Her eyes went over the tight, tired, plump face, and she smiled. “Ma,” the girl said, “when we get there, all you gonna pick fruit an’ kinda live in the country, ain’t you?”

Ma smiled a little satirically. “We ain’t there yet,” she said. “We don’t know what it’s like. We got to see.”

“Me an’ Connie don’t want to live in the country no more,” the girl said. “We got it all planned up what we gonna do… Connie gonna get a job in a store or maybe a fact’ry. An’ he’s gonna study at home, maybe radio, so he can git to be a expert an’ maybe later have his own store. An’ we’ll go to pitchers whenever… An’ after he studies at night, why – it’ll be nice, an’ he tore a page outa Western Love Stories, an’ he’s gonna send off for a course…”

Ma was right – no one knew what it was gonna be like. Rose was pregnant, so that’s literary, and Connie – ironically – wasn’t far off track in terms of how the future was going to work for those able to claim it. As in, NOT the Joads.

Ma was right – no one knew what it was gonna be like. Rose was pregnant, so that’s literary, and Connie – ironically – wasn’t far off track in terms of how the future was going to work for those able to claim it. As in, NOT the Joads.

Right at the end of that conversation, the truck carrying them all to California breaks down. That Steinbeck and his symbolism – what a nut.

Education became the new land. There were hints in the early 19th century, and Connie Rivers had a glimpse of it, but it takes awhile to remake the core of a faith. Enlightenment ideals certainly should have anticipated this, but the New World had far more available soil than acres of free pedagogy, so…

Sometimes the beliefs shape the facts, sometimes the facts shape the beliefs. Land it was, then.

By the time of the Cold War, starting with the G.I. Bill, the rules had somehow changed. From there forward it’s all going to be about who shapes the learning. As Schoolhouse Rock so wisely intoned, “It’s great to learn, because Knowledge is Power.”

Exactly.

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part I – This Land

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part II – Chosen People

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part III – Manifest Destiny

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part IV – The Measure of a Man

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part VI – Knowledge is Power

Related Post: 40 Credits & A Mule, Part VII – Sleeping Giants

Then crop failure, drought, and flood were no longer little deaths within life, but simple losses of money. And all their love was thinned with money, and all their fierceness dribbled away in interest until they were no longer farmers at all, but little shopkeepers of crops… Then those farmers who were not good shopkeepers lost their land to good shopkeepers. No matter how clever, how loving a man might be with earth and growing things, he could not survive if he were not a good shopkeeper. And as time went on, the business men had the farms, and the farms grew larger, but there were fewer of them…

Then crop failure, drought, and flood were no longer little deaths within life, but simple losses of money. And all their love was thinned with money, and all their fierceness dribbled away in interest until they were no longer farmers at all, but little shopkeepers of crops… Then those farmers who were not good shopkeepers lost their land to good shopkeepers. No matter how clever, how loving a man might be with earth and growing things, he could not survive if he were not a good shopkeeper. And as time went on, the business men had the farms, and the farms grew larger, but there were fewer of them… I

I  The Senate was intended to be the more austere, deliberative body – holding longer terms and intended as a balance on the more reactionary House of Representatives, elected every two years and thus presumably more responsive to the whims of the people. Jefferson’s parenthetical commentary is a nod to the superior role and trustworthy wisdom of the crude mess-secretors from a few sentences before.

The Senate was intended to be the more austere, deliberative body – holding longer terms and intended as a balance on the more reactionary House of Representatives, elected every two years and thus presumably more responsive to the whims of the people. Jefferson’s parenthetical commentary is a nod to the superior role and trustworthy wisdom of the crude mess-secretors from a few sentences before.

These few instances were reversed to smooth the transition into Reconstruction and maintain the almost cultish commitment Americans had to property rights – and, apparently, irony. The freedmen received nothing.

These few instances were reversed to smooth the transition into Reconstruction and maintain the almost cultish commitment Americans had to property rights – and, apparently, irony. The freedmen received nothing. You all remember Hayes, right? A President for whom it was worth giving up the closest we’d ever come to realizing our founding ideals?

You all remember Hayes, right? A President for whom it was worth giving up the closest we’d ever come to realizing our founding ideals? That’s the suffrage part. If Jefferson was correct about the spiritual and moral benefits of ‘laboring in the earth’, working the land of another may or may not have been worth partial divine credit. In terms of ‘vested interest’ in our national success, whatever support black Americans lent to their country came without terrestrial reciprocation.

That’s the suffrage part. If Jefferson was correct about the spiritual and moral benefits of ‘laboring in the earth’, working the land of another may or may not have been worth partial divine credit. In terms of ‘vested interest’ in our national success, whatever support black Americans lent to their country came without terrestrial reciprocation.

When my kids were little, we used to go to Bishop’s Cafeteria to eat with my dad. He was old, and old people like cafeterias – so we went.

When my kids were little, we used to go to Bishop’s Cafeteria to eat with my dad. He was old, and old people like cafeterias – so we went.

“DAD!”

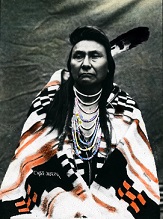

“DAD!”  I’m overgeneralizing, of course – there were hundreds of tribes and cultures and such – but by and large, they weren’t doing proper America things with the lands they claimed as theirs. And, as with the Jello, subjected to repeated wiggling but remaining unconsumed, our frontiersmen forebears weren’t impressed by the arguments of those claiming that land ownership requires neither cultivation nor mall-building.

I’m overgeneralizing, of course – there were hundreds of tribes and cultures and such – but by and large, they weren’t doing proper America things with the lands they claimed as theirs. And, as with the Jello, subjected to repeated wiggling but remaining unconsumed, our frontiersmen forebears weren’t impressed by the arguments of those claiming that land ownership requires neither cultivation nor mall-building.

Conflict with Mexico was not much different. Their culture was nothing like most Amerindian peoples, but neither did we particularly fathom or appreciate their social structure, economic mores, or anything else – nor they ours. Perhaps outright disdain for one another played a larger role than with the Natives, and certainly by that point the sheer momentum of Westward Expansion eclipsed whatever underlying values or beliefs had fueled it a generation prior, but whatever the immediate motivations, the same sense of unquestioned rightness oozed from the words and letters of those pinche gabachos

Conflict with Mexico was not much different. Their culture was nothing like most Amerindian peoples, but neither did we particularly fathom or appreciate their social structure, economic mores, or anything else – nor they ours. Perhaps outright disdain for one another played a larger role than with the Natives, and certainly by that point the sheer momentum of Westward Expansion eclipsed whatever underlying values or beliefs had fueled it a generation prior, but whatever the immediate motivations, the same sense of unquestioned rightness oozed from the words and letters of those pinche gabachos  They were assigned a value system and lifestyle they didn’t want, with the full weight of state and federal governments forcing compliance. They were assigned the worst land on which to practice this new system, and given inadequate tools and other supplies. The stakes were incredibly high – at best, they were expected to emulate those with the right equipment, in which case they could perhaps almost survive as second-class citizens. More likely, they would fail, starve, or simply give up – this not being a game they’d wished to play anyway.

They were assigned a value system and lifestyle they didn’t want, with the full weight of state and federal governments forcing compliance. They were assigned the worst land on which to practice this new system, and given inadequate tools and other supplies. The stakes were incredibly high – at best, they were expected to emulate those with the right equipment, in which case they could perhaps almost survive as second-class citizens. More likely, they would fail, starve, or simply give up – this not being a game they’d wished to play anyway.

“Those who labor in the earth…” I suppose he could have just said “farmers,” but this paints a more vivid picture to set up where he’s going. It’s not about a role in the economy or the food chain – it’s about the agency of individuals, applied not merely to ground or soil but to the “earth”. It’s a wide-angle lens on an idealized way of life – Jefferson’s strength.

“Those who labor in the earth…” I suppose he could have just said “farmers,” but this paints a more vivid picture to set up where he’s going. It’s not about a role in the economy or the food chain – it’s about the agency of individuals, applied not merely to ground or soil but to the “earth”. It’s a wide-angle lens on an idealized way of life – Jefferson’s strength. Farmers worked 365 days a year. Soil still needing tilling on your birthday, cows needed milked on Christmas, and no matter how sick you might be, those crops weren’t going to reap themselves. It was labor-intensive and the hours were long, and yet after doing all you could do, all day every day – you waited.

Farmers worked 365 days a year. Soil still needing tilling on your birthday, cows needed milked on Christmas, and no matter how sick you might be, those crops weren’t going to reap themselves. It was labor-intensive and the hours were long, and yet after doing all you could do, all day every day – you waited. Jefferson had a distrust of bankers, stock markets, or anything financial industry-ish – so much so that he took great personal pride in never having the foggiest idea how to make his estate solvent (he died in substantial debt). Farmers raised essentials. They produced raw materials which could be woven into clothing, smoked for pleasure, eaten to survive. “Real wealth.”

Jefferson had a distrust of bankers, stock markets, or anything financial industry-ish – so much so that he took great personal pride in never having the foggiest idea how to make his estate solvent (he died in substantial debt). Farmers raised essentials. They produced raw materials which could be woven into clothing, smoked for pleasure, eaten to survive. “Real wealth.” Land ownership promotes solidity, character, ethereal virtues reflected in wise words and actions – valuable in and of themselves, sure, but especially necessary in a nation relying on the people themselves to provide beneficial leadership – directly or through their choices regarding representation.

Land ownership promotes solidity, character, ethereal virtues reflected in wise words and actions – valuable in and of themselves, sure, but especially necessary in a nation relying on the people themselves to provide beneficial leadership – directly or through their choices regarding representation. That he so easily adjusts his faith to accommodate current events I leave to you to interpret as you see fit.

That he so easily adjusts his faith to accommodate current events I leave to you to interpret as you see fit.